‘Sex class is so deep as to be invisible.’

So begins American feminist Shulamith Firestone’s 1970 global blockbuster The Dialectic of Sex. I remember vividly the first time I read it as an undergraduate: I’d certainly encountered feminist texts before, but none like this. Who was this person who told us frankly that love ‘is the pivot of women’s oppression today’, that childbirth was like ‘shitting a pumpkin’, who declared that her ‘dream action for women’s liberation’ was ‘a smile boycott’? Who was this 25 year-old with the intellectual chutzpah to declare that ‘Really, Freud can be embarrassing?’ Shulie’s voice rang clear across the decades between her writing and my reading; her words – direct, authoritative, funny – seduced me and showed me a new way of being. Shulie tells the truth to you straight about the world, and men’s power over women, with no apologies. And if men don’t like it? Well then, good. Who wants to please men anyway?

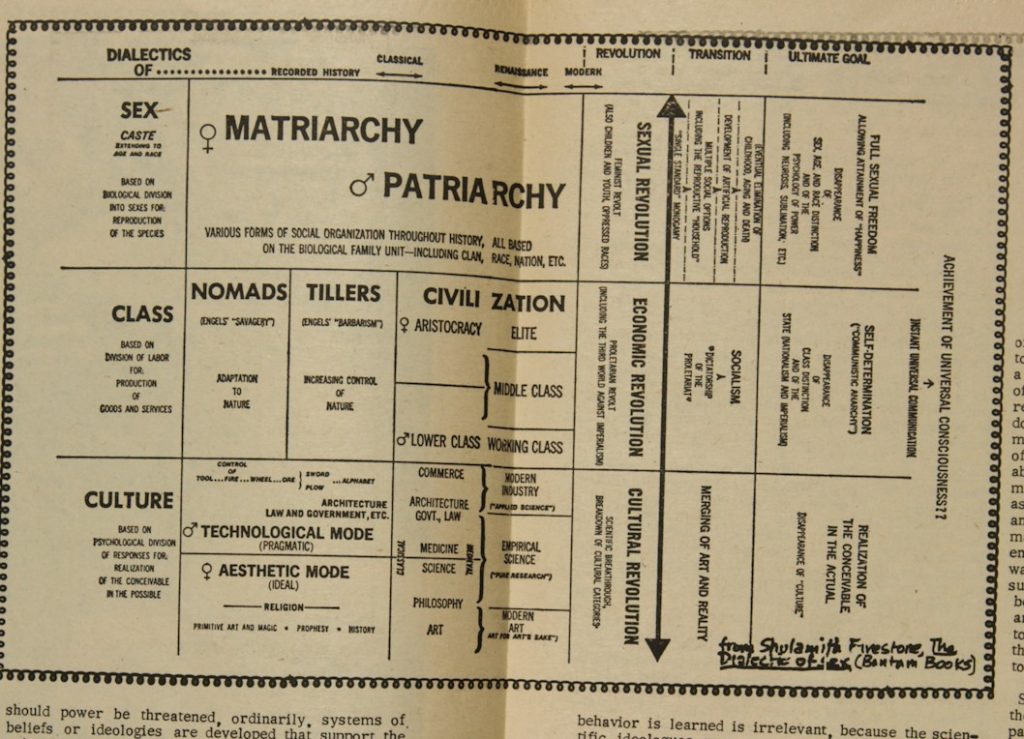

What’s more, whilst feminist texts I’d read previously seemed to offer little more than a counsel of despair – few appeared to be able to imagine a world where patriarchy was abolished – no-one could accuse Shulie of not having a plan. Not only did she look forward to ‘not just the elimination of male distinction, but of the sex distinction itself’, but her final goal? Nothing less than the Achievement of Cosmic Consciousness, brought about as a result of Instant Universal Communication! The book has a chart to show us:

Here, feminism-meets-communism-meets-science-fiction; dialectics meet test-tube-babies. I’m a historian of feminism, and truly, I still have no idea what this chart is on about 15 years after I first came across it. I love it for its ambition, though: Shulie wrote in what I call feminism’s utopian moment, a short period between about 1968 and 1972 when anything seemed possible, and the world was up for grabs.

It’s fair to say that the intervening years have somewhat dampened my initial ardour for Firestone’s ideas; she’s certainly, in the lexicon of our time, a problematic fave. Unlike Shulie, I don’t really think that women’s oppression is a product of their biological difference (a concept which itself has come to be questioned by feminists such as Judith Butler); I think that ‘seizing the means of reproduction’, whilst a great line, is unlikely to lead to liberation; and I certainly hope that her reductive analysis of racism – which she deemed as ‘the sexism of the family of man’– would have no place in the more intersectional feminism of 2021. But it’s the way that Firestone can all at once seem to be speaking to us very directly today, and yet simultaneously bewilder and appal us, which has come to interest me as a historian. Why? I’d argue that the reaction she provokes in us suggests that we’re not yet done with the feminist past that she represents.

From the moment I encountered her, I wanted to find out more about Firestone, but Google in 2005 was not yet the total repository of human knowledge that it has since become, and I was confused to find only one more book that she had written: 1998’s Airless Spaces, a collection of seemingly autobiographical, sort-of-short-stories set among the down and outs of New York. I read it and realised that the intervening years had not been kind to Shulie; in fact, she had suffered a serious mental breakdown in the mid-1970s from which she never really recovered before her death in 2012. Obituaries were full of her early dynamism and promise; I longed to know what Shulie would have been like as a young radical, working for a revolution she believed to be just around the corner. I imagined her to be like her writing: charismatic, irreverent, incandescent.

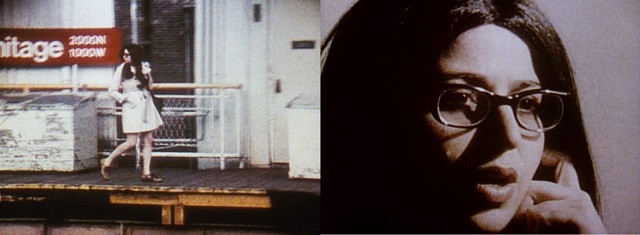

So I was intrigued when I heard about the director Elisabeth Subrin and her first film Shulie. Subrin, whilst working at the Chicago Institute of Art in the mid-90s, found in its archives a film reel for a documentary project made by the Institute’s students in the late 1960s. The subject? Firestone herself. Herself a student at the Institute at the time, Shulie had already garnered a sufficient reputation for her politics, her radicalism, her charisma, for her course-mates to make her the subject of a film. Subrin watched it, and was so struck by the documentary that she decided to remake it shot-by-shot, in an act of what she called ‘conceptual time-travel’. By so doing, Subrin did not just simply recreate a lost historical document, but also, in her words, sought to ‘investigate the mythos and residue of the late ‘60s’. Through recreating Shulie 30 years later, Subrin suggested that the questions that Firestone raises were still pertinent in the 1990s, and posed more subtle questions about how the past haunts the present. When are we ever done with ‘history’? And how do we live with the ghostly presence of a revolution that never came to pass?

The result made Subrin’s name as an artist and director; The New Yorker called Shulie ‘a thing of wonder’. Nevertheless, the film, though shown at many festivals over the years, has never been commercially available. As such, I’m just delighted that CFAC have generously provided the funding for an online screening; I’m even more excited that Elisabeth Subrin herself will be joining us in conversation afterwards. I hope that at least some of you can join us in watching a film that I, at least, have been waiting 15 years to see.

You can book your ticket for this event which will take place online on Thursday 29 April, 19:00 – 20:30.

Dr Natalie Thomlinson is Associate Professor of Modern British Cultural History in the Department of History.