The Tokyo 2021 Olympics will be the first Games to take place with no spectators. The sight of sparsely populated stadiums and arenas has, of course, become common during the pandemic – and sports economists have studied the impact this has had on athletic performance.

But the Olympics are different. For so many athletes, reaching the four-yearly Games is the crowning achievement of their careers. So there was bitter disappointment when at first international and then domestic visitors were banned from events.

Now all athletes in Tokyo will be performing to venues largely emptied of all fans. But this will be more keenly felt by Japan’s Olympic team, who would have dreamed of performing in front of their own fans. And how will the empty arenas affect their ability to capitalise on home advantage?

A supportive home audience is one of the four factors to which home advantage in professional sports is routinely pegged. Others include athletes not having to travel, being familiar with home conditions and favourable referee bias.

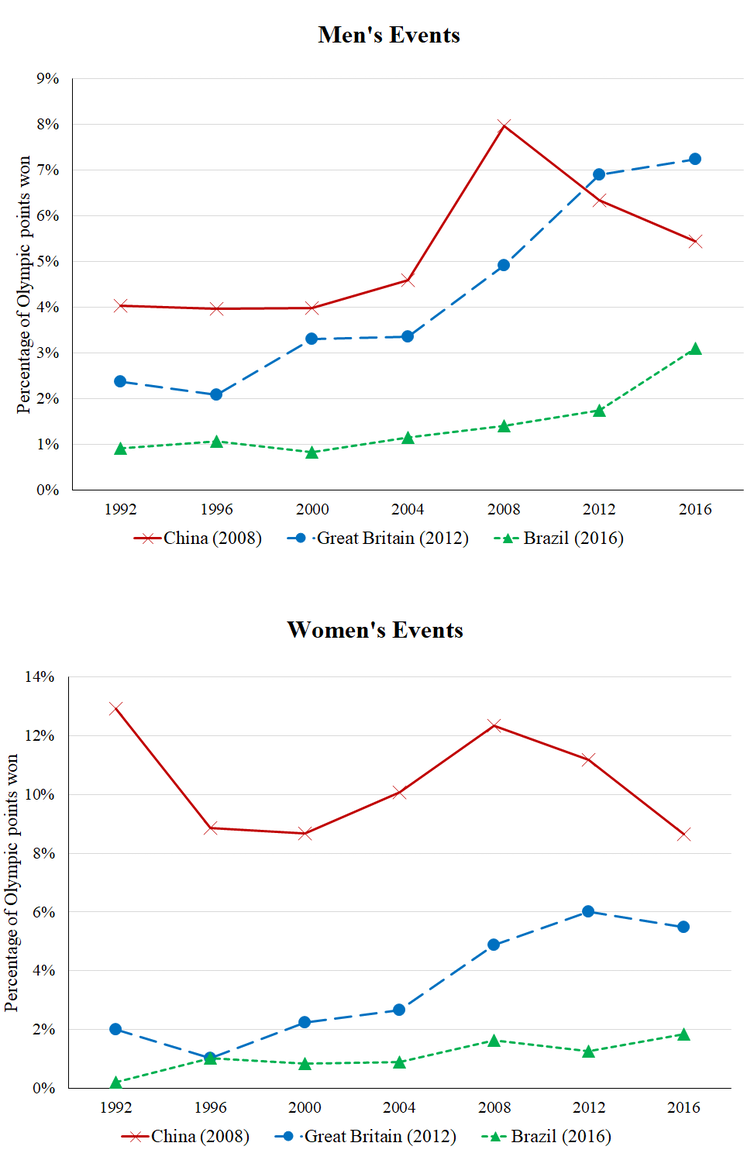

The hosts of the last three summer Olympics – Rio 2016, London 2012 and Beijing 2008 – did unusually well too, gaining a higher proportion of Olympic success, as measured in medals and finalists, in both men’s and women’s events compared with the previous Games. In terms of gold medals only, Brazil went from three to seven between 2012 and 2016, Great Britain went from 19 to 29 between 2008 and 2012, and China went from 32 to 48 between 2004 and 2008.

Percentage of Olympic points in men’s and women’s events, won by host nations of the last three summer Olympic Games, 1992-2016. Uses data from the International Olympic Committee and Olympics.com. Olympic Points are summed over all men’s or women’s events in a Games according to the following: Gold=5, Silver=3, Bronze=2, Finalist=1.

We have quantified the general home advantage effects, throughout the modern Olympic period, from 1896 to 2016. Unlike most research to date, we have looked at both summer and winter Olympiads, and at sports held under very different conditions – with or without judges, inside or outside a venue, with many or few spectators.

Modern Olympic history

We looked at the percentage of all available gold medals won by the host nation for each summer and winter Games in the modern era, from Athens 1896 to Rio 2016, for men’s and for women’s events.

In the early years the host had a substantial advantage. At the 1932 summer Olympics in Los Angeles, the US team won 28% of the gold medals available in the men’s events and 70% in the women’s events. This advantage then declined over time as the diversity of countries and athletes participating has increased, raising competition. At Rio 2016, 207 countries were represented, compared with just 37 countries in 1932.

Percentage of all gold medals in men’s events won by the host nation at the summer and winter Olympic Games, 1896-2016. Uses data from the International Olympic Committee and Olympics.com.

Percentage of all gold medals in women’s events won by the host nation at the summer and winter Olympic Games, 1900-2016. Uses data from the International Olympic Committee and Olympics.com.

Several studies have estimated the effect of hosting the Olympics on the success of home teams and individual athletes. Typically, they have found that it depends on the sport and the athlete’s gender.

By comparing how countries performed when hosting and when not, we estimate that hosts of the summer Olympics could expect on average a two percentage-point increase in their share of success across disciplines, for both men’s and women’s events. Assuming finalists and bronze medals were unaffected, this corresponds to Japan approximately turning every seventh silver medal into gold because they are competing at home.

We also found that the home advantage effect has been 50% greater at the winter than the summer Olympics since 1988 in men’s events. We found no advantage for female athletes from hosting at the winter Games.

Great Britain may have achieved fewer golds in 2016 compared with their home games in 2012, but the overall medal count went up, from 67 to 69. In general, we found that spillover effects of hosting the summer Games on the previous and next Olympiads are normal.

Compared with the year of actually hosting the summer Games, the boost in success in men’s events was one-third as large as in the previous Games, and half as large as in the next Games. But these spillover effects from hosting do not tend to appear at the winter Games.

Tokyo without crowds

Sports economists and psychologists have studied how the absence of fans has affected performance during the pandemic. Much attention has focused on football, where studies have found reduced home advantage in matches played behind closed doors.

This is caused in part by how referees could make decisions without the pressure of a home audience. Similar effects have been noted in rugby.

Not all Olympic sports, however, attract a raucous crowd that inspires performances or pressures the referees. Previous research found a significant host advantage in judged sports (such as gymnastics), but not in track and field athletics or swimming, where audiences are typically huge, but officials seldom influence outcomes. And even in stadium and arena events, Olympic crowds are typically more international and less partisan than at a Premier League football match.

Japan’s athletes will also still have favourable home knowledge and experience of the conditions on site (the climate, routines, and venues). These might, however, somewhat be reduced due to the cancellation of Olympic test events and the COVID measures on-site, which remain extraordinary compared to other years.

International athletes, meanwhile, will have had to travel to Tokyo. And all participants who do not live in Japan will have had to quarantine at their accommodation upon arrival for at least three days.

Therefore, Japan is still likely to do well. A strong showing by the host nation matters. While the economic benefits of hosting are minimal despite their ever increasing costs, research has shown there are other positive benefits, from increased sports participation among citizens to a sense of national pride, happiness and wellbeing.

Carl Singleton is Associate Professor in Economics, University of Reading. Dominik Schreyer is Assistant Professor of Sports Economics, WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management. Johan Rewilak is Lecturer in Economics, Finance and Entrepreneurship, Aston University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.