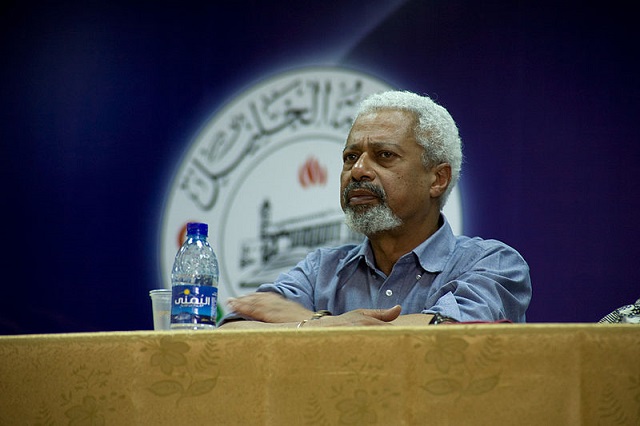

NPR, the US American public radio station, was broadcasting some critical reporting on the day of the announcement of the 2021 Nobel Literature Prize, 7 October. The journalists were discussing that, while the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong’o had been nominated many times, surely again the Nobel Committee would name not an accomplished and celebrated author from the global south, let alone a black writer, but to what many would be an obscure artist or eccentric choice of usually a white male from the west. Then the news broke that Zanzibari born Abdulrazak Gurnah won the Prize, the only second black African author, after Wole Soyinka from Nigeria in 1986, among a list of white writers from the region spread across 1957 to 2008. This set news agencies scrambling to find information on Gurnah and his work.

Much can be noted about this, not least considering that in addition to older forms of oral literature such as epics, Africa’s rich literary output since the mid-20th century in the genre of the novel has not merely added to or enriched the literary corpus. A British colleague pointed out to me a few years ago that literature is what was written by British authors up to 1900 and another colleague added that of course in English lessons at school one reads authors whose first language is English. The range of views on what that corpus encompasses still includes a significant articulation of ignorance, white privilege, and indeed what Robin DiAngelo coined ‘white fragility’, here the fear that ‘the other’, i.e. in this case non British English writers, the global south, black authors, has produced art that does not just rival but that stands shoulder to shoulder with works from the west.

When fellow Zanzibari born and British based artist Lubaina Himid won the Turner Prize in 2017, annually awarded to a British Artist (based or born), she was the first black woman to achieve this prestigious honour since its inauguration in 1984. Himid emphasises how much her positionality as a black woman informs her art and chosen role as a cultural activist. In whatever manner Abdulrazak Gurnah wishes to identify – black, Zanzibari, diasporic, after having lived the majority of his life in Britain – his art must be foregrounded in this critical discourse of the asymmetry of power in cultural, economic, and global relations between the west and the global south.

The Nobel Prize committee issued the Literature Prize announcement and press release with this explanation: Gurnah won ‘for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents.’[1] This author cannot claim to have read all of Gurnah’s literary output. But there are two aspects that as an Africanist and gender historian one may take some issue with. The verb ‘penetration’ is an unfortunate choice for various reasons not least because it has been shown that it represents an androcentric and sexualised view of power and forcefulness that was part of the colonial and imperial discourse.[2] More importantly, one particularly celebrated work by Gurnah is his tremendous novel Paradise (1994) which is a beautiful, troubling, and wonderfully complicated exploration as a coming of age story of a boy, Yusuf. It is set in the early colonial period in what today is Tanzania, consisting of the mainland, first colonised by Germany as German East Africa from the late nineteenth century – and then after World War I handed over by the League of Nations to Britain as mandated territory when it was renamed Tanganyika – and the islands of Zanzibar which were under British rule. Both gained independence in the early 1960s and after a revolution in Zanzibar chose to join as the Republic of Tanzania in 1962. Gurnah carefully situates the novel indicating that German rule had arrived without engaging the theme of colonialism at all. Instead of, to paraphrase the Nobel announcement, ‘penetrating the effects of colonialism’ what Gurnah does brilliantly in this novel that made him globally famous is to look into the complexities of Swahili society and the lived experience of a boy pawned by his parents from a Swahili town in the interior to the coast.

The complex negotiations that characterised identities of the western Indian Ocean became even more pronounced in the nineteenth century. The volume and geographic reach of the East African slave trade increased after abolition in the Atlantic, and the Sultan of Oman moved his capital city to Africa, anointing himself the Sultan of Zanzibar, as it was here where the emirate was generating its wealth and where direct control of the merchant activities was important, with the main palaces facing the harbour, with the warehouses at their feet. The exceptional choice of composing this coming of age story of a boy before abolition of slavery on the islands of Zanzibar in 1897 and on the mainland in 1922 was, when first published, and is to this day mesmerising and astonishing. Who could one be in this world? With the boy Yusuf experiencing both bondage and accompanying a slave trading caravan into the interior, first love across ethnic boundaries with the complicated articulations of slave, Swahili (free or unfree), Indian, and Arab as some of the identities, in a predominantly Muslim world where Islam having arrived a thousand years before, the reader is literally and metaphorically taken on a moving exploration of self. One of the uncomfortable identity markers is the African and Arab othering of non-Muslims as washenzi (Kiswahili: barbarians, uncultured people) in contrast to Muslims as ustaarabu (Kiswahili: civilised). In the understanding of the time washenzi could be enslaved.

The novel Paradise challenges western stereotypes of Africa as a continent of tribes, as Africa predominantly shaped by the black Atlantic, as Africa south of the Sahara a Christian world region threatened by recent Islamicist extremism. It takes the reader on an at times uneasy path, accompanying Yusuf growing up as he negotiates manliness and masculinity and tries to find a place in the world he inhabits, something that existentially all humans do as a rite de passage through puberty. For many westerners, and especially those with white privilege, that lived experience appears safe, achievable, and certainly well-deserved. What maybe is most astonishing about Gurnah’s literary achievements is that he weaves narrative without pointing an educational finger. His art invites the reader to travel and explore the human experience that we all share, takes us to raw and even painful places but also the magically beautiful and secluded garden where Yusuf experiences the longing of first love.

[1] The Norwegian Nobel Prize Committee, https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/2021/press-release/, 7 October 2021.

[2] Much has been published since. For an early treatment, see H. I. Schmidt, ‘”Penetrating” Foreign Lands: Contestations over African Landscape. A Case Study from Eastern Zimbabwe’ Environment and History 1, no. 3 (1995), 351-376.

Heike Schmidt is an Associate Professor in the Department of History.