Most of what we know about the beginnings of English professional theatre as a financial enterprise and artistic endeavour comes from thousands of manuscript pages in the archive of Philip Henslowe (1550–1616) and his son-in-law and business partner, the actor Edward Alleyn (1566–1626).

Henslowe and Alleyn financed many acting companies, including Lord Strange’s Men, the first to employ Shakespeare, and Lord Admiral’s Men, the important troupe of its time. These manuscripts, currently held at Dulwich College, London, comprise the largest and, arguably, the most important existing archive of material about professional theatre in early modern England.

Among the manuscripts are the only surviving records of box office receipts for any play by Shakespeare (Titus Andronicus and Henry IV) and Christopher Marlowe (Doctor Faustus, The Jew of Malta and Tamburlaine).

The manuscripts remained stored in Alleyn’s locked trunk, in their original folded condition, for 260 years, and access to them was gained through visits to the college’s library. For many years, they remained uncatalogued, and sticky-fingered visitors purloined pages, sending fragments of the archive across the country and later the world.

In 2004, I founded a project to digitise these records. By 2022, with the help of other scholars and the archive at Dulwich College, I had reunited all the known fragments, as well as pages of correspondence, legal documents, receipts and other records for the first time in more than 200 years.

Thieves and scholars

In the early 18th century, rumours began to spread about the uncatalogued archive and a stream of people went to Dulwich College (a school founded by Alleyn) determined to unlock the history of Shakespeare’s dramas, playhouses and performances.

As well as box office receipts, Henslowe and Alleyn’s archive includes the sole surviving actor’s “part” (or script) of the age from the play Orlando Furioso and the “plot” (or prompter’s outline) of the anonymous play The Second Part of the Seven Deadly Sins, one of six plots from this period known to survive.

The archive also includes the 1587 partnership deed between Henslowe and his associates to build the Rose Playhouse on London’s Southbank and the 1600 contract between Peter Street, who built the Globe Playhouse, and Henslowe and Alleyn to build the Fortune Playhouse in north London.

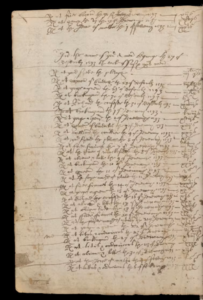

The most important document in this archive, and in English theatre history, however, is Henslowe’s account book. This document provides detailed records from 1597 to the early 1600s of payments to Ben Johnson, Thomas Middleton, Henry Chettle and many other playwrights. The document mentions more than 325 commissioned plays, many of which no longer exist, as well as transactions with royal and local officials, actors, censors, costumers and other theatre workers. It also features many signatures (or valuable autographs to thieves).

As scholar and editor Edmond Malone announced in an addition to his influential Historical Account of the Rise and Progress of the English Stage from 1790, the document completely reshaped the understanding of early modern English drama.

Pages go missing

Unfortunately, Dulwich College librarians weren’t so vigilant in protecting this important archive. They allowed some visitors unsupervised access to the manuscripts – many of whom didn’t leave empty-handed. The most infamous of these thieves was the Shakespearean scholar and notorious forger John Payne Collier. Collier not only read the “diary” for his scholarly works on Henslowe and Alleyn but also pilfered pages.

Collier pasted pages he stole into a literary autograph scrapbook, which he later sold to the British Museum claiming he had found them in various bookshops. Other collections sold to the British Museum included fragments also compiled by Collier or those he sold them to.

In the 1880s, the manuscripts were finally catalogued in more than 20 volumes by the British Museum’s assistant keeper of manuscripts, George Warner. Warner understood their immense importance to England’s cultural history and recognised that some items had been stolen over the centuries.

Luckily, the noted Shakespearean bibliographer W.W. Greg played literary detective, locating most of the fragments, many still uncatalogued, while preparing his first edition of the diary in 1904.

But, as the Shakespeare scholar R.A. Foakes mentioned in his 1961 edition of the diary, at least 69 pages were still missing and others were removed or partially cut out by autograph hunters. Fragments of some of these pages, with the signatures of poet George Chapman, playwright Thomas Dekker and others, found their way into 18th- and 19th-century auctions and later into manuscript collections at the British Museum, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire (discovered by Greg in 1938) and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington DC.

Since the 1800s calls by Dulwich College librarians for the return of these documents have been met with polite refusals.

With the help of Calista Lucy, keeper of the archive at Dulwich College, I contacted all the librarians responsible for these pilfered items, asking if I could upload them to the electronic archive.

The academic Paul Caton and I have now uploaded all the known fragments, along with letters, deeds and other manuscripts – digitally reuniting the diary and the archive for the first time in over 200 years.

Grace Ioppolo is Professor Emerita, and formerly Professor of Shakespearean and Early Modern Drama, at the University of Reading.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.