Digital and physical book subscription packages soared during lockdown. And according to trade organisation The Bookseller, they look set to continue to do well, despite the cost-of-living crisis. These packages come from various places – the brainchild of independent booksellers, lifestyle and brand entrepreneurs, or small and large publishers. But what they all have in common is providing consumers with some form of curation and selection, along with ‘edutainment’ and pleasure. Receiving a little something through the post each month is a gift you make to yourself that combines fun and surprise with the promise of future rewards. Whether that’s books and wine, feminist books, or a book on sale or return that would have otherwise been pulped, depends on your tastes and values.

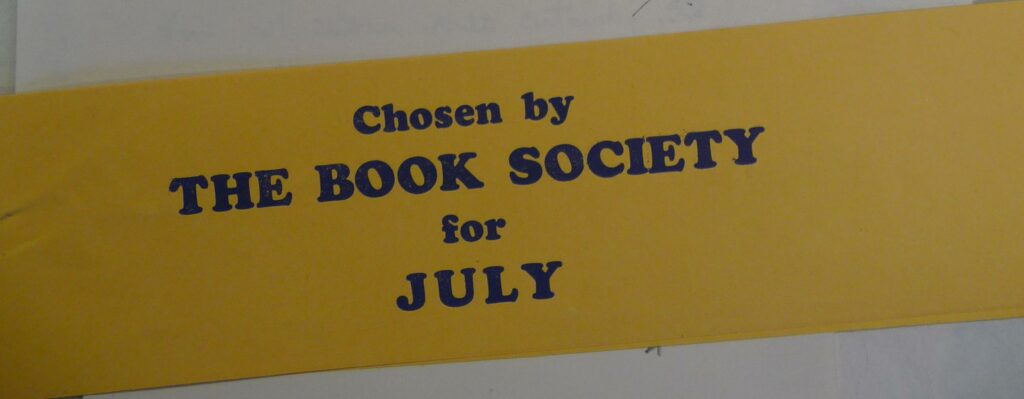

As part of a University Research Fellowship (2022–3), I’m writing a book on the first book subscription company in Britain. The Book Society (1929–69) was set up by a consortium of publishers and retailers to boost books sales and change reading habits in a period when it wasn’t common to own or buy books. In the late 1920s, more affluent readers paid to borrow books from circulating libraries on the high street like Boots Book-Lovers Library (part of Boots the pharmacists), W. H. Smith, or The Times Book Club. The Book Society and other cheap subscription book clubs that came later, including the Readers Union (founded 1937) or Victor Gollancz’s Left Book Club (1936-), was set up to change this.

The Book Society was headed by a group of celebrity writers and critics. Bestselling novelist Hugh Walpole led the selection committee, working alongside writers J. B. Priestley, Sylvia Lynd, and Clemence Dane, WW1 poet Edmund Blunden and ‘30s poet’ Cecil Day-Lewis, Oxford academic and public intellectual Professor George Gordon. Thousands of members – worldwide – appreciated their services. By the early 1930s they had over 10,000 subscribers and continued to have a major influence on publishing (and print runs) throughout the Great Depression, the rise of fascism and during the Second World War.

To some, the club was part of a reading revolution that was shaking up and democratising the book world. In 1938, socialist Margaret Cole compared the Book Society’s effects on books to ‘the influence which, in the course of a generation, has brought gramophone records, silk stockings, foreign travel, and smoked salmon … within the reach of small purses’.[1]

But the judges also faced snobbery and criticism. The Book Society were ‘conferring authority on a taste for the second-rate’ said Cambridge academic Q. D. Leavis in one of the first widespread surveys of reading patterns.[2] Bookshops were up in arms initially, fearing they’d lose trade. But it quickly became clear that non-members were also following the club’s recommendations, boosting sales across the board. They had become ‘a standard of literary advice very well respected throughout the country’ advised Boots Book-Lovers’ Library after WW2. ‘Even people who do not belong to the Book Society are prepared to order these volumes through libraries’, they reassured staff, ‘so that most publishers are exceedingly pleased to have one of their titles chosen’. [3]

I first discovered the Book Society in the archives of Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press at Reading’s Special Collections. Leafing through folders of publishing correspondence, I couldn’t get over the regularity of traffic between Britain’s first, controversial book-of-the-month club, and what I thought I knew as a small, modernist press. A lot of the Book Society letters received by Leonard Woolf are apologies and rejections, saying the club couldn’t choose or review the Hogarth Press books they’d been sent. But the Woolfs did hit the jackpot occasionally, benefitting from the additional sales and global publicity of what publisher Harold Raymond described as ‘the Book Society bun’.[4]

Writing the first history of the Book Society has been challenging. Club records haven’t survived so I’ve picked through judges’ personal papers and letters, riffling sales and other publishing data, absorbing rare surviving copies of the monthly Book Society News. Unlike the American Book-of-the-Month Club (BOMC) which still exists and which the Book Society was modelled on (you can watch BOMC members unboxing on YouTube), very little is known about the first subscription book club across the Atlantic. And yet, because of Britain’s colonial context, the Book Society mailed new books out to tens of thousands of readers in countries across the Anglophone-speaking world for over forty years. Writing this book, I’ve been contacted by people trying to understand their relatives’ book collections, from the family of a farmer in Tanzania, to descendants of one of the first British women doctors working in Canada.

I’ve decided on a book format that combines group biography with the history of popular reading, as it’s the judges’ messy personal lives that often dictated what they sent out. This story of how many twentieth-century classics reached readers as Book Society Choices has been all but forgotten. But it needs unearthing so we can put today’s book subscription packages in proper context. Bethan Ferguson, Hachette’s Feminist Book Box lead recently said that ‘One of the reasons that people are cagey about it is because it’s a new business model for us, I mean this is not something that is in publishers’ DNA, so there’s learning to be done.’ Part of what I want to do with the Fellowship aims to highlight the much longer history of book subscription packages, as well as uncovering the foundational role played by the judges of Britain’s first celebrity book club.

Nicola Wilson is Associate Professor in English Literature at the University of Reading and a recipient of a University Research Fellowship 2022–3.

[1] Margaret Cole, Books and the People (London: Hogarth Press, 1938), p. 5.

[2] Q. D. Leavis, Fiction and the Reading Public (1932; Harmondsworth: Peregrine, 1979), p. 34.

[3] Boots Book-lovers Library, First Literary Course, “Ninth Paper: Publishers and Bestsellers”, box 460, Alliance Boots Archive & Museum Collection, Nottingham.

[4] Harold Raymond to Margaret Irwin, October 16, 1936. University of Reading, Chatto and Windus 63/2.