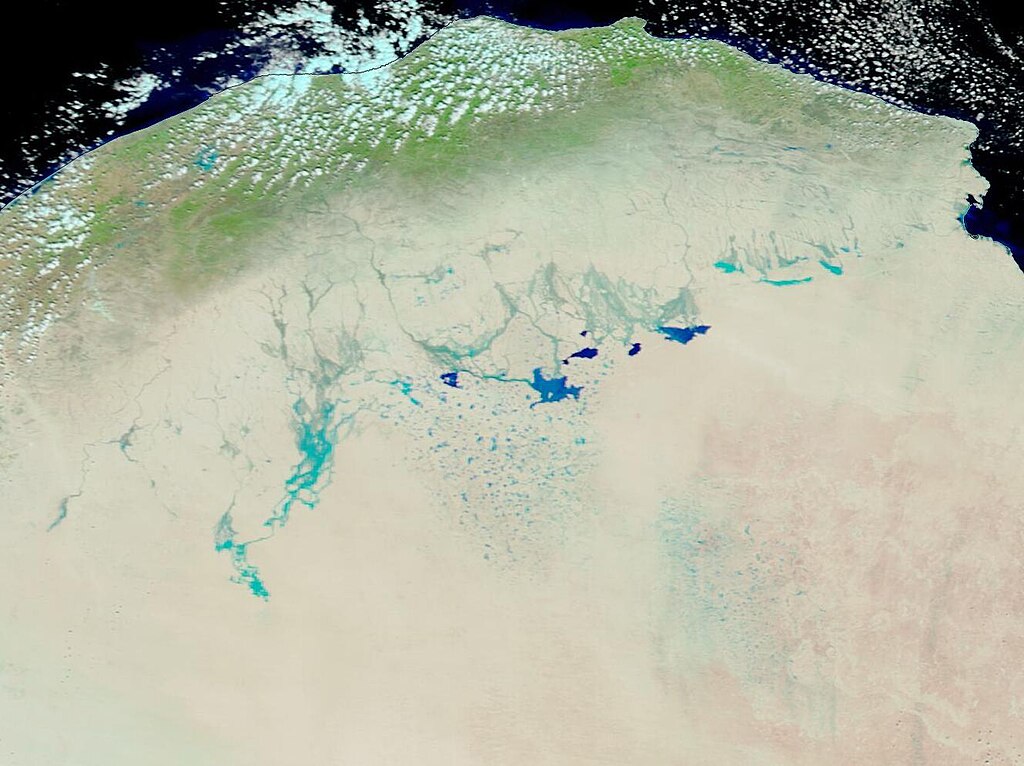

A century ago, the coastal city of Derna was well known for picture-perfect beaches, palm trees and whitewashed villas mainly inhabited by Libya’s Italian colonial occupiers. Today, in the aftermath of Storm Daniel, which brought 400mm of rain to the region, overwhelming two dams and sweeping millions of tons of water across the city, much of Derna has been flooded. Entire suburbs are reported to have been washed into the sea by the tsunami-like wave that barrelled down the normally dry river Wadi Dern through the heart of the city.

The death toll from the catastrophe is estimated at more than 11,000 with another 10,000 missing and feared dead. Countless more people – perhaps one-third of Derna’s inhabitants, have been left homeless.

Derna has been a centre of resistance to successive Libyan regimes. The former Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, regarded the city with distrust and deprived it of basic resources and infrastructure. On the eve of Gaddafi’s overthrow by Nato-backed forces in 2011, the Libyan government described Derna as a “hotbed of Islamic fundamentalism”.

In the vacuum left by Gaddafi’s overthrow and the civil war that followed, Derna became a centre for jihadis who pledged their allegiance to Islamic State in 2014. From 2015 to 2018 the city was besieged by Libya’s eastern warlord Khalifa Haftar and his Libyan National Army (LNA).

As a result, the city has suffered from decades of neglect and much of its infrastructure dates back to Italian occupation of the country in the early 20th century. The city has no proper hospital and no schools.

As many as 20,000 people are feared dead in Derna, Libya, after two dams failed. The UN says most of these deaths could have been avoided, so why has the disaster taken such a toll? Libyan politician @Guma_el_gamaty blames neglect and bad planning https://t.co/6faz83HVnY pic.twitter.com/kTQOfbs86K

— BBC World Service (@bbcworldservice) September 14, 2023

The Wadi Derna dams that collapsed with such fatal consequences were built in the mid 1970s by a Yugoslav company as part of a project to provide irrigation for the region and drinking water for Derna and other local communities. There are two dams: the biggest, Derna, is 75 metres in height and has a capacity of 18 million cubic meters of water. Mansour is 45 metres and holds 1.5 million cubic metres.

A research paper published in November 2022 said the two were at risk of collapse. In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, Derna’s deputy mayor admitted the dams had not been maintained since 2002.

Divided country

The situation in Libya is exacerbated by the fact that in the civil war that followed the fall of Gaddafi, the country has essentially become split in half. The western region is governed from Tripoli by prime minister Abdul Hamid Dbeibah and his UN-approved Government of National Accord, which took power in 2015 with the promise of holding national elections which have yet to be called.

The east is administered from Tobruk by a National Assembly, established in 2014 and headed by prime minister Osama Hamad. But the real power lies with Haftar, the commander of the Tobruk-based Libyan National Army (LNA). Despite not being internationally recognised, the east (which is in reality the majority of Libyan territory, including vast desert areas in the south) has the lion’s share of Libya’s oil wealth.

In 2020, Haftar overplayed his hand in an unsuccessful attempt to seize Tripoli. This led to a UN-brokered ceasefire and the current uneasy de facto division of power between east and west in Libya.

Even before the devastation of Storm Daniel, Libya was in the throes of a humanitarian crisis. In 2021, the UN estimated that more than 800,000 Libyans were in need of aid after two decades of fighting and unrest and little in the way of reconstruction.

International efforts have hitherto largely depended on Tripoli’s approval to allow aid to reach the east. And even once that is given, the task is made more difficult by the fact that bridges and roads connecting the two parts of the country have been badly damaged in the civil war.

An opportunity to work together?

One can only hope that the scale of this tragedy becomes a catalyst for a more functional working relationship between the two regions and the international community. There have been tentative signs that this might be the case. The two governments have demonstrated a willingness to cooperate in recent days and the Dbeibah government in Tripoli has sent a flight with medical supplies and personnel to the disaster zone.

Despite the historic level of animosity between east and west, there have been precedents where the rival have been forced to cooperate on shared interests. Earlier this year, the rival administrations agreed to form a committee to manage the distribution of oil revenues which form the backbone of Libya’s economy.

International aid is beginning to reach the disaster zone. Though the international community does not officially recognise Haftar-led regime, it will inevitably be the primary player in managing and mitigating the effects of this crisis.

Countries that want to help the Libyan citizens most affected will have to work with the Haftar-backed leadership. It is hoped this international engagement could thereby play an important role in facilitating a rapprochement between the two parts of the country.

Both Libya’s governments have called for an inquiry into the disaster. The chairman of the Presidential Council, Mohamed al-Menfi, based in Tobruk, said the inquiry should “hold accountable everyone who made a mistake or neglected by abstaining or taking actions that resulted in the collapse of the city’s dams”.

Libya’s attorney general, Al-Siddiq Al-Sour, who is based in Tripoli but officially has jurisdiction over the whole country, called for an investigation into allegations local officials imposed a curfew on the night Storm Daniel struck.

But before any blame is apportioned, the rescue operation must be given priority by both governments, who will need to take a proactive, pragmatic and principled attitude towards working together in the interests of the whole country. Far-fetched as this may seem, it could be a valuable learning experience for both sides.

Lecturer in Middle Eastern History at the University of Reading.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons Licence.