We must “bulldoze through” the planning system to “get Britain building again”. So said Sir Keir Starmer at the Labour party’s last annual conference. He argued it’s time to “fight the blockers” and build the 1.5 million homes that he thinks Britain needs.

But it is simplistic to lay all the blame on our “restrictive” planning system. Our research indicates that relying on a small number of large and highly profitable private housebuilders to provide most of Britain’s new homes is also a major part of the problem.

The shortfall in housing supply (particularly the supply of affordable housing) has coincided with the state’s exit from large-scale housebuilding after the mid-1970s. Housing came to be seen as something that should be provided predominately by the market.

However, the market did not match previous levels of housing supply. Instead, the private housebuilding industry has consolidated so that it is now increasingly dominated by “volume housebuilders”. These large, publicly traded businesses control significant amounts of development land and dominate housing output.

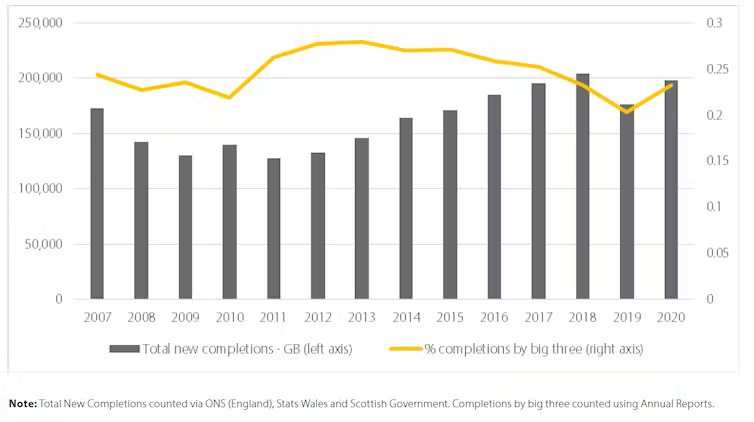

The three largest housebuilders (by number of houses built) regularly produce about 25% of all new homes, while the top ten typically produce about 40-50%. This means the government relies on a small number of private businesses to deliver most new housing. But their collective supply consistently falls short of targets. For example, the total number of additional new homes from all sources in England was around 233,000 in 2021-22 against the government’s target of 300,000.

To find out why this is happening, we combed through the discussions the UK’s three largest housebuilders – Persimmon, Barratt and Taylor Wimpey – have had with their investors on earnings calls between 2007 and 2018. This helped us examine their business practices, as well as their relationship with the government.

Profit over volume

In the years following the 2008 global financial crisis, the “big three” housebuilders that dominate the new-build market in Britain have been able to increase their profits without significantly increasing the number of homes they build. This has happened despite political pressure to increase UK housing supply.

Housebuilding completions

They were able to do this, we argue, because they have built up significant structural power: they can use their control of housing land and housebuilding to secure state support for initiatives that benefit their shareholders by pushing up their share prices and profitability. Persimmon and Taylor Wimpey did not respond to a request for comment on this article, while Barratt declined to provide a comment for publication.

The companies have had a receptive audience in government. Evidence from government documents suggests policymakers were nervous about the threat to housing supply that would arise if the business operations of volume housebuilders didn’t receive state support.

As a result, housebuilders have been able to secure government mortgage market support schemes – such as Help to Buy, introduced in 2013 – that were aimed at releasing pent-up demand for new homes. Research shows these schemes have inflated new build sales prices in some circumstances.

These reforms have particularly benefited the volume housebuilders over their small and medium-sized competitors. Indeed, the big three alone consistently attracted significant levels of funding from mortgage market support schemes, accounting for 43% of transactions under one such scheme in the period 2013-2017. They were also able to renegotiate their obligations to local planning authorities, including affordable housing contributions.

The “big three” housebuilders declined to comment on this article on the record but a spokesperson for industry group Home Builders Federation (HBF) pointed out that net housing supply in England almost doubled between 2013 and 2019, claiming larger builders delivered most of the increase.

“The authors’ report correctly suggests that the planning system and its processes disproportionately impact negatively [smaller builders],” he added. “The policy and legislative changes in planning and beyond over the past 30 years have incentivised scale and footprint.”

Liberalisation of planning

At the same time, the big three exerted pressure to liberalise the English planning system in 2012, which had the effect of increasing the supply of large, greenfield sites (previously undeveloped land) that generally only the larger housebuilders have sufficient finance to develop. This increase in the supply of large greenfield sites, combined with the relatively small number of housebuilders in a position to develop them, resulted in reduced competition in the development land market.

The then-group operations director of Taylor Wimpey even pointed this out in May 2018, noting that “everybody in the industry has been telling you [investors] for several years how much easier the land environment is, how much, much better the returns are, how much less competition there is”.

We argue this state support via planning liberalisation has given volume housebuilders what’s called monopsonistic market power in local land markets. In other words, it’s created a buyer-dominated market. This has kept the cost of their land relatively flat while UK house prices continued to rise.

You can see this in the graph below, with the yellow line showing what we would have expected to happen to greenfield land prices in a competitive land market, and the pink line showing what has actually happened (at least according to real estate company Savills’ land agents).

When market power in local land markets was combined with structural power over the state, we believe volume housebuilders were able to increase their profit margins rather than ramp up delivery to help the government meet its target of 300,000 new homes per year in England. Our research shows it was in the interests of the volume housebuilders not to rapidly increase their housing supply for two main reasons.

First, significantly increasing supply would have meant them building out sites more quickly, depressing their sales prices. Second, it would have meant them increasing their demand for land, thus increasing their land costs. As the then-group chief executive of Taylor Wimpey disclosed in July 2013: “like any oligopoly, there’s a balancing act. If you … try and push your market share … you move the whole market and that’s going to damage us all”.

Again, the big three declined to comment but the HBF spokesperson said house builders can’t set house prices, which are pegged to local markets and independently valued by buyers’ mortgage lenders. “Housing supply is cyclical and builders’ profits reflect that,” he added. “Successful companies attract investors, that allows greater investment in land and skills and local communities as more homes are built.”

A way forward

The UK is moving into another downturn in housing supply. Rather than repeat the failures of the past, any future government needs to recognise that planning liberalisation alone is unlikely to lead to a major increase in housing supply while volume housebuilders apparently continue to prioritise increasing profit margins over increasing volumes. Nor is it likely to significantly increase the supply of the affordable homes that are most needed.

The state enjoys significant structural power over housebuilders via the planning system, taxation and building regulation. The government must recognise this power and use it to take a more direct and active role in delivering new and more affordable housing. We need a more positive and better-funded planning system, rather than simply “bulldozing” through it.

Lecturer in Housing Economics at the University of Reading. Senior Lecturer in Planning and Development at Cardiff University.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons Licence.