What good are the humanities on a burning planet? What use is a poem about flowers when the world’s biodiversity faces cataclysm caused by climate change? What is the point in celebrating the humanistic values of studying languages, literatures, and history at a time when war crimes are committed against those whose humanity is denied? These were the thorny questions discussed at an event to launch the newly reconfigured School of Humanities at the University of Reading.

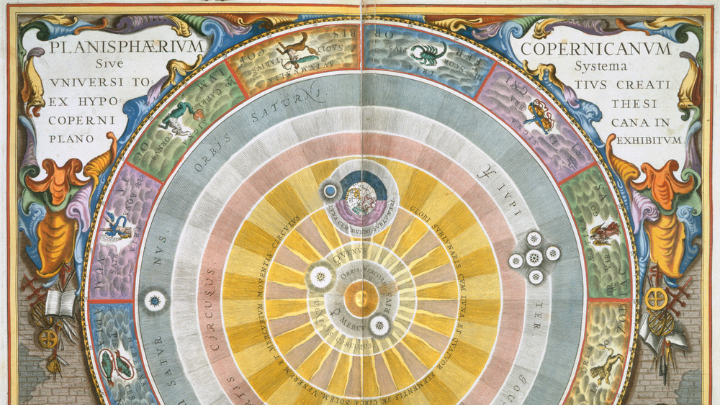

Image: Copernicus’ world system, from the Atlas Coelestis (Amsterdam, 1600) demonstrates humanism’s drive for knowledge, at the same time as alluding to its anthropocentrism. Credit: From the British Library archive.

The idea of ‘the humanities’ goes back at least as far as ancient Rome. In 62 BCE, the Roman statesman Cicero delivered a speech in defence of his former teacher, the Greek poet Archias. Archias was on trial for falsely claiming Roman citizenship. In defence of his old teacher, Cicero praised the poet’s cultivation of studia humanitatis ac litterarum, the study of culture and literature. The text of Cicero’s speech would later be lost, only to be rediscovered in 1333, in a library in Liège, Belgium, by the Italian poet and scholar of classical antiquity, Francesco Petrarca.

Petrarch, as he is known in English, is often credited with being an early proponent of humanism – the careful study of the literatures of ancient Rome and, later, ancient Greece too. The perceived revival in the late Middle Ages of the learning of ancient Greece and ancient Rome would, in the nineteenth century, come to be known as the Renaissance.

It was also in the nineteenth century that universities began to group scholars into departments dedicated to humanistic learning, rooted in the Renaissance study of Greek and Latin literature. And so we encounter the emergence of the School of Humanities.

Yet humanism has also authorised terrible acts of inhumanity.

It was partly as a result of the rediscovery of ancient geographical knowledge that Europeans sailed westwards across the Atlantic. The genocide of the indigenous peoples of the Americas was justified in part by notions of ‘just war’ drawn from Latin literature. The enslavement of Africans looked to Aristotle’s notions of ‘natural slavery’ for support. The Roman historian Tacitus’ description of ancient Germans as a race that has not mixed with others allowed the National Socialists to anchor their racism in antiquity. Meanwhile, in the face of climate collapse, the humanities’ emphasis on humans has given rise to humanity’s self-centredness which abnegates us as a species from our responsibilities to the planet.

What responsibility, then, do modern Schools of Humanities have when encountering these legacies?

At our ‘Humanities Day’, contributions tackled issues ranging from non-western humanisms, to the challenges and opportunities presented by AI; or from tracking non-humans – mosquitoes – in colonial India as a mechanism of surveillance of human subjects, to what it means for our humanity when we lose the ability to speak. Dr Mara Oliva and Dr Dawn Kanter also delivered a session on Reading’s strengths in the Digital Humanities, presenting exciting new research opportunities and areas for collaboration.

The discussions were bookended by keynote speakers invited from beyond the University of Reading. Marchella Ward, Lecturer in Classics at the Open University, opened proceedings with a wide-ranging and thought-provoking lecture on ‘Humans, Humanity and the Humanities: Searching for critical disciplines among the ruins of a colonial order’. Sketching out the genealogy of the humanities and its relationship with humanism, shows us how the humanities have allowed some groups to be excluded from ‘humankind’ (e.g. during Europe’s colonial endeavours, and the mass-enslavement of African people), but also how critical approaches to the humanities offer hope from ‘the ruins of a colonial order’. And a critical approach to the humanities can show us how to envisage the type of future that we want for ourselves and for our planet, and can serve to guide our actions.

Ralph Pite, Professor of English at the University of Bristol, closed the day with a powerful assertion of what the humanities have to offer in the context of the climate emergency. Literature, and especially poetry, encourages us to look at the world in a way that science cannot. We know the science that tells us that climate change presents an existential threat to life on the planet, but literature makes us feel it, and, it is hoped, stirs us into action.

In an era when higher education policy is increasingly aligned with market priorities, the humanities sometime fall into the trap of trying to articulate their ‘value’. Yet, as the history of humanism and the way that the humanities encourage us to imagine the world differently shows, it is precisely in their power to question preconceived values that the value of the humanities are situated.

The newly amalgamated School of the Humanities brings together students, teachers, and researchers with a dazzling array of expertise and interests but all united by a common aim of examining what it is to be human in our rapidly changing world.

Samuel Agbamu is a Lecturer in Classics and co-organiser, alongside Professor Emma Aston, of the ‘Humanities Day’ which we plan to make an annual event, looking at the interconnections between and beyond our disciplines. The new School of Humanities comprises the Departments of Classics, English Language & Applied Linguistics, English Literature, History, and Languages & Cultures.