I am 27 years old; I have no money and no prospects. I am already a burden for my parents, and I am frightened. So don’t judge me, Lizzie.

So spoke Charlotte Lucas, a “thornback”, on the prospect of marrying the “ridiculous” bachelor Reverend William Collins. Lucas is a character in Pride and Prejudice (1813) by Jane Austen, the dowdy best friend to the brilliant protagonist Elizabeth Bennet. However, these words are not Austen’s but were written by Emma Thompson for the Pride and Prejudice movie in 2005.

You might have seen the term “thornback” social media recently as single women try to reclaim it. If you are young and single, it seems like a fabulously witchy word to call yourself but it remains a sexist term that reduces women to a marital coalition.

The origins of “thornback” are murky but it is generally agreed that it was used for unmarried women over the age of 26 or 27. It is believed that the word was first used in a translation from the French Gargantua and Pantagruel or The Five Books of the Lives and Deeds of Gargantua and Pantagruel by François Rabelais published between 1532 and 1564 (but I have to be honest here, I haven’t read them in any detail).

Later in 17th-century New England, the word was used to describe both older unwed women and a flat fish which had spines on its back and tail – a reference to unattractiveness and we can assume the expectation of a sting or pain on encountering them.

British society has always had a need to name unmarried women. One of the most common terms is “spinster”.

Technically, all unwed women are spinsters although historically, unmarried women were often referred to as “maids” reflecting their youth and virginal status. The assumption was that this was a temporary but formative time of a young woman’s life, in preparation for marriage and a change in status once wed. As such, there is an allusion to youth and inevitability.

By the 14th century, the word “spinster” had first emerged and by the 18th century, it was used to describe an increasing number of single women who might never marry at all. During the mid-19th century, with the advent of a ‘surplus’ of women, the prospect of spinsterhood became a financial as well as a social issue, especially for middle-class ladies. What was to be done to make these thornbacks useful? This prospect led to the development of modern women’s education.

In 1837, Henry Colburn, a book publisher and the co-founder of the New Monthly Magazine, tried to delineate the status of unwed women at any age in The Spinster’s Numeration Table. For Colburn, women of 26 or 27, had “hair and shoulders growing rather thin. Ventures upon luncheon. Reads Mrs. Marcet, cultivates a flower garden, and affects decided opinions.”

In other words, she is beginning to look older and take up hobbies that a bride-in-waiting would not, such as her flower garden and engaging in the intellectual works of Mrs Marcet, an early proponent of science and economics – a dig at educated women.

An unmarried woman of 30 in The Spinster’s Numeration Table “thinks it possible to pass ten months of the year in the country. Assumes a cap for morning visits, and reads tracts on the education of the poor.”

These women were considered beyond engaging in fashionable society, so far beyond the expected age of marriage that all that was left to them was modesty. Such modesty is why they would have a cap covering their hair in the same way that many modest women covered their hair as a matter of course when married, while also carrying out philanthropy or good works.

At 32, she adopts a dreaded feminist tone becoming “serious. Quotes from Hannah More, and replaces the specked tooth with a Mallan. Thinks it possible to pass the year round in the country with a man one esteems — Wonders how anybody can care for diamonds.”

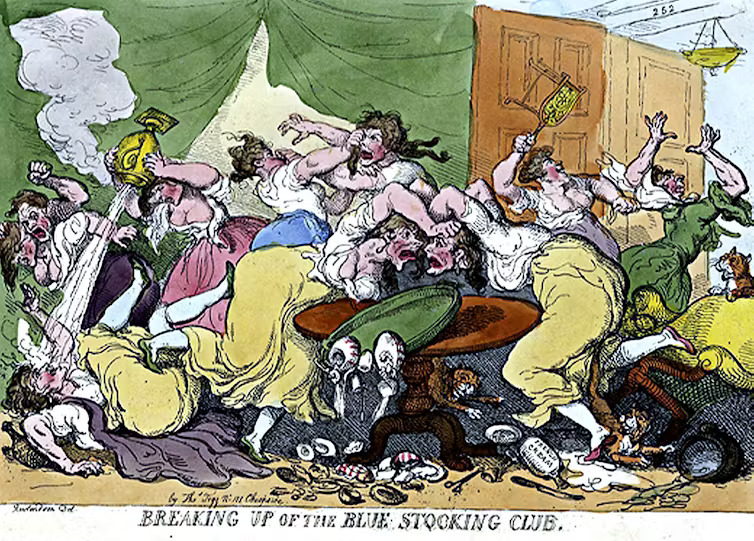

Hannah More was an early feminist and published on moral topics. She became involved in women’s education and was a leading “bluestocking”. Bluestocking was a word that developed to describe, and often deride intellectual women. Originally it came from the 18th-century Blue Stocking Society, a literary group of women who met regularly. However, Moore was religious and her attitudes were very conservative so it’s difficult to consider her a feminist in the modern context.

The bits about teeth and diamonds are reference to how Coburn believes a woman of this age is becoming less attractive and less concerned with being so. She suffers from rotting, chipped and discoloured teeth, which need to be replaced with false ones or a mallan.

According to The Spinster’s Numeration Table, when a woman turns 55 and remains unmarried “she assumes brevet rank. Becomes an esprit fort, and is thenceforward classed in our minds with beings of an epicine gender.”

She is getting older, beyond marriage and childbearing, but without increased income or privilege. “Brevet rank” is a a temporary military promotion but is scornfully used here to describe her more senior status in a negative manner. “Epicine” means a lack of gender. This is just a very long-winded way to say she becomes sexless. Charming, right?

Today, the word “thornback” remains a pejorative term that references the contradiction of being older and unwed. It has parallels with the historic term “old maid” with the inference of unnatural virginity in a woman beyond the traditional western marrying age.

Of course, the average age that people marry has shifted though time and by geography faith and culture. But I think rather than trying to resurrect a word for single women over a certain age, we should just create new ones that aren’t solely about having or not having a partner.

Jacqui Turner, Associate Professor in Modern History, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.