I recently watched the actor Ian McKellan, playing Shakespeare’s iconic character Sir John Falstaff, announce that he had drawn together an army made up of prisoners to fight for King Henry IV against Harry “Hotspur” Percy of Northumberland. Henry the IV, a play set in fifteenth century England, is about the history of King Henry IV, his relationship with his son, and his struggles to maintain power. Falstaff is a slothful figure, a jester who is synonymous with debauchery. The audience laughs uproariously when he announces that he’s assembled an army made entirely of prisoners: ‘such as indeed were never soldiers, but discarded unjust servingmen, younger sons to younger brothers, revolted tapsters, and ostlers trade-fallen, the cankers of a calm world and a long peace, ten times more dishonorable-ragged than an old faz’d ancient… A mad fellow met me on the way and told me I had unloaded all the gibbets and pressed the dead bodies’. The idea of this ragtag army brought together by such an absurd figure, who seems incapable of fighting himself, resonated with the audience. Shakespeare’s Henry IV is set in fifteenth century England, yet armies continue to be made up of people from prisons and marginalised communities, sacrificed for the cause of war. This form of sacrifice is something that remains squarely in Western traditions, as best exhibited through the use of people convicted of crimes as soldiers. The Russian government is reported to have recruited over 100,000 people from prison to fight on the frontlines of the Ukrainian war, treated like cannon fodder. According to one formerly incarcerated soldier who was interviewed by the New York Times about his commanders, ‘we are not human to them‘.

Fodder is food for cattle or other livestock. Ironically, the first reference to soldiers as a kind of “food” was in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, where Falstaff describes his rag tag army as ‘Good enough to toss; food for powder, food for powder. They’ll fit a pit as good as better’. The men he’s using as disposable – exchangeable for gun powder. Cannon fodder is also a term of sacrifice. These men are expendable. So much of our contemporary discourse on mass imprisonment focuses on the deeply harmful effects of incapacitation – from the humiliations of everyday life under a guard’s watch, to the often-intergenerational health problems, mental health crises, and the structural effects of millions of people spending years of their lives in such a punishing system. Some journalists, scholars, and people who are incarcerated have written about aging behind bars, deaths and suicide in custody. But less considered are the ways that the criminal justice system has been used as a vehicle for sacrifice, and how these past practices might echo into contemporary forms of punishment.

Sacrifice is often associated with rituals that seem long ago and far away. Or, in the modern day, with religious rituals or events. For example, lambs may be sacrificed during the Islamic holiday of Eid-al-Adha. Christians may sacrifice a type of food during Lent. Yet, the notion of humans being sacrified is often considered considered morally repugnant in the West – identified as something that people Westerns condemn do, such as suicide bombing.

I first discovered this link to sacrifice during my research on the history of convict transportation to the Americas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. During this period, over 50,000 people were sent from England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland to the America colonies as a form of punishment. There, they served seven to fourteen years as labourers, often in very brutal conditions. But it was during this time, in the mid eighteenth century, when the Seven Years War, and the wars between the English, Spanish and Native Americas, demanded labour and so the English pressed these “convicts” into military service. According to historian Roger Ekirch, ‘The Earl of Loudon, as commander-in-chief of British forces, claimed in 1757 that many of Virginia’s recruits included felons ‘brought out of the Ships before they landed”. Treated like the goods unloaded from boats alongside them, these men were quickly pressed into service. The scholar Hamish Maxwell-Stuart estimates that there were approximately 15,000 men convicted of crimes who served in the British army in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. With an estimated 60,000 English deaths during the Seven Years War, the futures of these men would have been imperilled by their convictions. Researchers have established strong links between incarceration and premature death, largely stemming from the poor conditions of confinement, lack of access to adequate healthcare, ineffective disease prevention, and the compounding effects of exposure to the stressors of incarceration. The COVID-19 pandemic put this issue into relief: according to the Health Foundation, people in prison in England and Wales experienced three times the death rate from the epidemic compared to the general population.

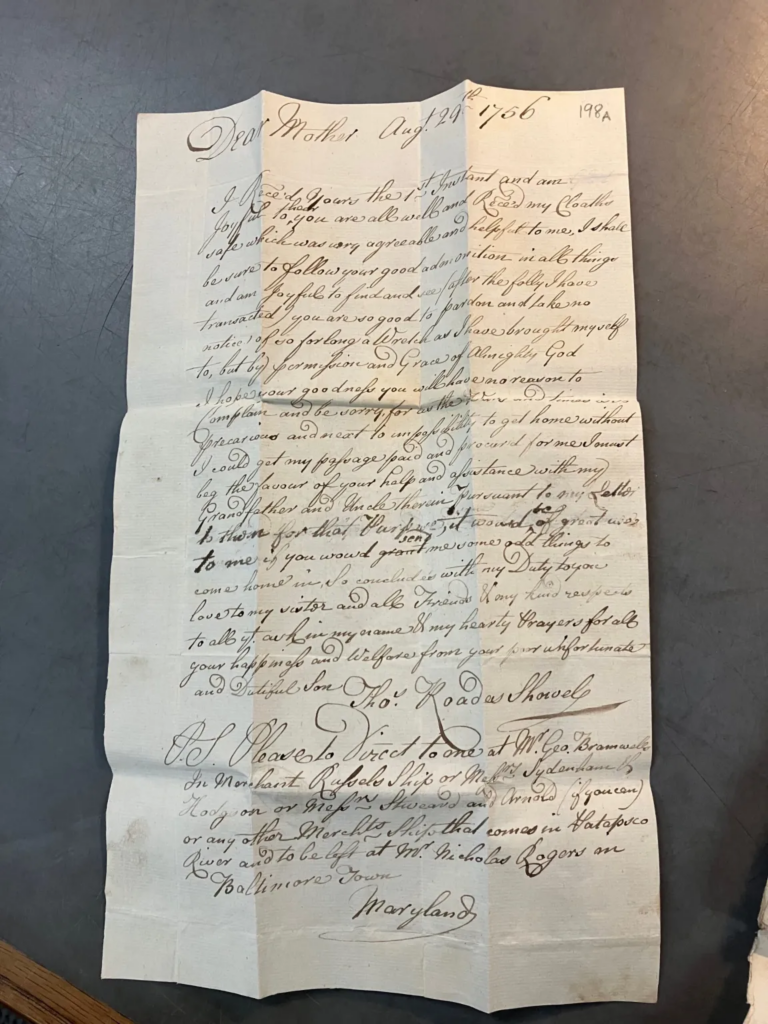

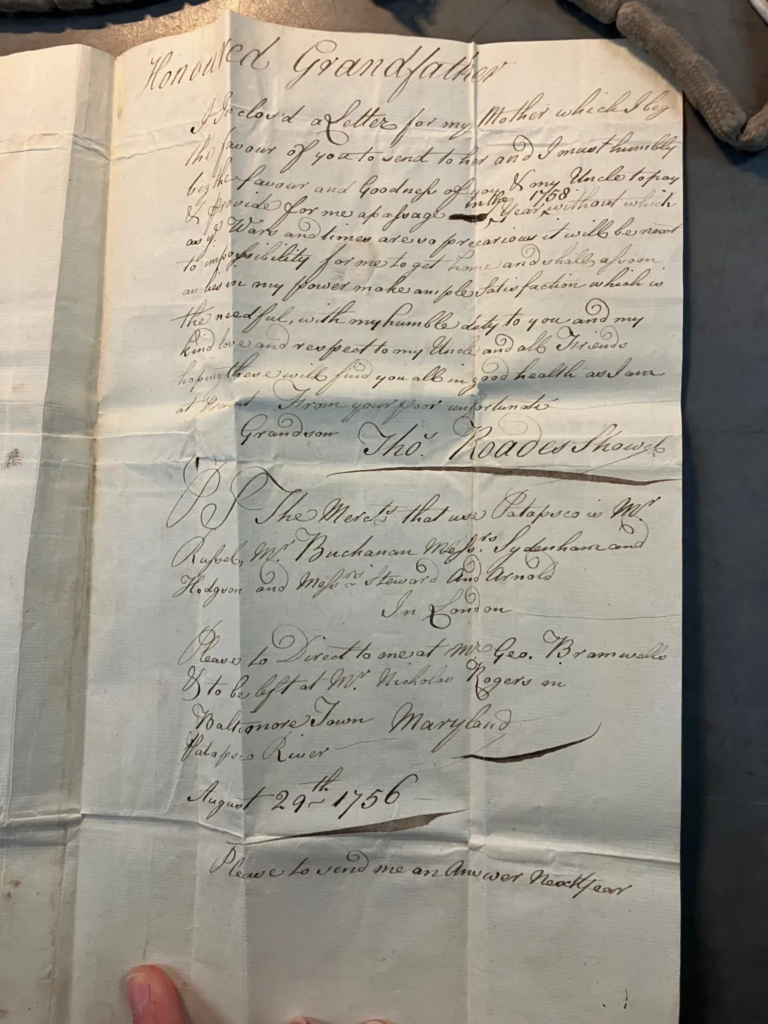

We know very little about the lives of the people transported to the Americas during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and who may have been forced into military service. Many of the 50,000 people who were transported there were illiterate, lacked resources to tell their stories, or died premature deaths in the inhospitable and punishing New World. Some traces of their lives survive in the form of wills and probate records. Some sensationalist accounts were told in pamphlets and booked which crossed the Atlantic. Yet we have a new resource which can give us a glimpse into their lives: recently, the English National Archives have catalogued a trove of letters, part of a collection called the Prize Papers, that were sent from colonists home to their families in the eighteenth century and which were on a ship, the Enterprize, which was captured by a French privateering ship on its voyage from Maryland to London in 1756. In the bundles of letters on that ship, we found two that convey the terror that transported men and women might feel at the prospect of the war and what it would bring for them.

The letters were from a man called Thomas Rhoades Showle, who was probably sentenced to transportation in 1739 from Gloucestershire. He directed the first letter to his grandfather, and the second to his mother. In them, he begged for passage home. Most people like Thomas would have received a seven-to-fourteen-year sentence to transportation, so his sentence must have concluded by 1756, when he wrote the letters. He begs his grandfather’s support for his passage home, saying that because it is a time of war, ‘times are so precarious it will be next to impossible for me to get home’. The next letter is to his mother, who he thanks for giving him grace ‘after the folly I have transacted…for long a wretch I have transacted myself’. He again repeats that the times are ‘precarious’ and that he could only get home if his passage was paid for him. Thomas’s letters to his family are desperate and pleading – and speak to the trap he found himself in after being transported to Maryland and completing his sentence in hard labor. While we don’t know if there was a direct threat that Thomas would be forced into the war in that period, but it certainly would have been common for young men like him to be. His desperation to leave the colonies suggests his possible awareness of this threat.

The disposability of the young men and women who were sent to the American colonies speaks to their knowledge of, in Thomas’s words, how precarious their existence was. Shakespeare’s decision to use an army of men released from the gallows as the brunt of a joke in his text reveals a great deal about the disposability of the lives of individuals in the minds of those of the time. The precarity of a criminal conviction continues to endure today. What is less well-discussed are the ways that the lives of people with convictions might make them more vulnerable to sacrifice.

Ironically, a criminal record now complicates the process of joining the US and British armies, but being in the army can be a pipeline to prison. Many branches of the military in the United States now bar people from joining as an alternative to incarceration. Florida state legislators recently proposed to allow young people with misdemeanour convictions an option of enlisting in the military instead of going to prison, but that legislation didn’t pass. And yet, that does not preclude the military from engaging in predatory recruitment practices in America’s and England’s most deprived and marginalised communities. For the young men and women who join the British and American military, their lives can be significantly and negatively altered by military service. And as we are increasingly learning, veterans are making up a growing percentage of individuals in the criminal justice system. According to the US Council on Criminal justice, ‘one-third of veterans report a history of arrest, compared to one-fifth of the non-veteran population‘. The moral and political complexity of the most recent global conflicts that members of the American and British military have faced is extraordinary, as well as the serious and long-lasting consequences of exposure to improvised explosive devices and other weapons of war. There is an irony in this contemporary form of sacrifice of young men and women: not only have they faced premature death for their service, but that service also exposes them to serious and long-lasting harms that make them more vulnerable to arrest and conviction.

It may seem easy in these times to see the practices that Putin engages in with impressing prisoners into war service as morally repugnant and dangerous, but the legacies of Anglo-American military sacrifice remain with us today.

Alexandra Cox, Associate Professor at the University of Reading School of Law

Dr Cox previously worked in the Department of Sociology at the University of Essex. She has spent many years working in and researching the American and British justice systems, including as a Soros Justice Fellow. She is the author of the book Trapped in a Vice: the Consequences of Confinement for Young People (Rutgers University Press).

This article is republished with permission from History Workshop. Read the original article.