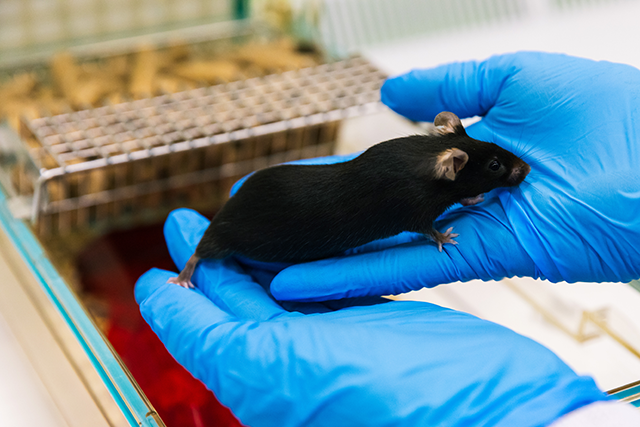

Though controversial, animal research is an important part of some work at the forefront of scientific and medical discovery. While every effort is made to keep their use to a minimum, some research can only take place with the use of animals. There is a growing global emphasis on humane research practice, recognising the intrinsic value of animal welfare and the ethical responsibilities of researchers, Here Cheryl Yalden reflects on a recent event held at the University, to discuss the ‘culture of care’ and practical ways to nurture this culture.

In animal research, a ‘culture of care’ refers to the organisational commitment to promote an environment in which ethical practices and continuous improvements are central. The priorities of this culture of care are:

- Animal welfare: Ensuring that animals are treated with compassion and respect, minimising pain and distress, and providing enrichment to improve their quality of life. Home Office legislation dictates minimum standards for animal welfare. A culture of care seeks to go beyond a culture of compliance.

- Staff well-being: Supporting the mental and physical health of staff involved in animal care and research, recognising the emotional challenges they may face.

- Scientific quality: Promoting lofty standards of scientific integrity and rigour, ensuring that research is conducted ethically and responsibly.

- Transparency: Being open and honest with the public and stakeholders about animal research practices and welfare standards.

The implementation of the 3Rs principles for animal research (Replace, Reduce, Refine) is a core component of this culture. These principles aim to replace animals with alternative methods wherever possible, reduce the number of animals used, and refine procedures to minimise suffering.

With this in mind, the University recently hosted a symposium to bring members of the animal research community together to discuss issues specific to promoting a Culture of Care. Many other meetings, especially for academics, can be very scientific and not as animal or staff focused. One of the aims of the meeting was to encourage scientists to attend and engage with other members of the community, thus promoting an inclusive culture within our teams and labs.

The symposium started with a discussion of training and competency. presented by the director of the Biological Services Unit at the University of Oxford. This emphasised the necessity of comprehensive training for everyone involved in animal research. It also tackled the issue of reassessing competencies and how regular this should be done to ensure good compliance but not to overwhelm staff.

Further talks focused on engaging with the public on animal research, refinements for handling and habituation, implementation of the 3Rs, mindset and compassion fatigue. We ended off the day with a ‘Mouse Exchange’ activity, during which we all created a mouse out of felt and other materials while discussing what we had learned from each other and how we can all help to promote a culture of care.

There were three main takeaways from the day. First, training and competency are foundational to ensuring high welfare standards. The integration of ongoing education into research practices is essential for fostering a knowledgeable and skilled workforce and maintaining best practice.

Second, positive reinforcement methods are useful to reduce the stress animals may feel from handling , and can lead them to readily accept simple procedures, e.g. oral dosing, as it is associated with reward. This improves the health and welfare of the animals and the staff working with them. It also creates less variation between animals and therefore results in more reliable and reproducible science.

Third, it is important for staff working with research animals to recognise and acknowledge their mindset and their mental health. Practices were shared that could help individuals do this. Suggestions on how to reduce compassion fatigue and burnout were also shared.

The symposium was an opportunity to talk about best practice, compassion and openness in animal research and the feedback from attendees was overwhelmingly positive. We now need to plan for how we can keep the dialogue ongoing.

Cheryl Yalden, Technical Manager of the University’s Biological Resources Unit