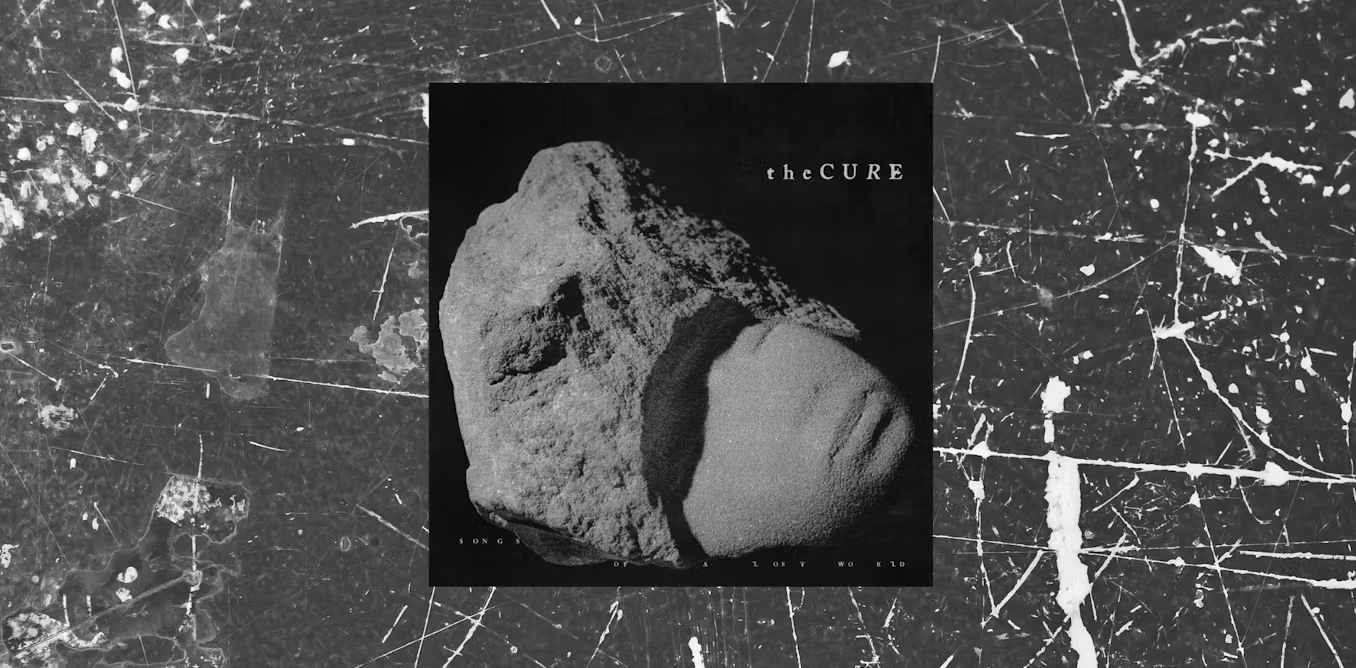

At Shrewsbury train station, there is a poster advertising The Cure’s new album, Songs of a Lost World. The confident, monochrome minimalism of the art is at odds with the rambling Victorian brickwork, yet there is a kind of sympathy there also.

At ten on a November morning, the station isn’t the most joyful of locations and so is a suitable home for a record praised for its wintery desolation. The poster helps here.

The cover art features a sculpture called Bagatelle from 1975 by the Slovenian artist Janez Pirna, which the cover’s designer chose because he pictured it “floating in space, almost as a distant relic from a forgotten time”. It also includes a new custom font, called Cureation, which is distressed and austere, and references the font used originally by the band. Like the station, these choices call upon a previous age – a lost world.

Songs of a Lost World is The Cure’s first album in 16 years. Reaching number one in the UK and now the US, some might argue it casts a pall of darkness over the pop charts; others might say it glitters a little in their reflected light. This has always been the way with The Cure.

On one side of their catalogue, we have what is known as the “unholy trinity” of early albums Seventeen Seconds, Faith and Pornography: alienated, austere, thematically dark. On the other, the shambling psychedelia of The Top and Kiss Me, the latter also featuring the blissed-out pop that helped this quintessentially English band find success in America.

In his recent book Goth: A History, the band’s former drummer Lol Tolhurst charts the genre from its 18th-century literary beginnings to its modern musical incarnation. In it, he describes how The Cure’s sound sits within this history through its unexpected influences, which range from record producer Phil Spector’s “wall of sound”, the production technique behind pop hits for The Ronettes and The Supremes, to the poetry of TS Eliot.

While Tolhurst locates the band’s sound within the gothic, frontman Robert Smith has consistently rejected the label. The difficulty in framing the band and this new album as gothic is that, like The Cure, the gothic has always been made up of contradictions.

Although nostalgic for medievalism, the gothic employs imagery that was called on by the theorist Karl Marx when discussing the alienating effects of modernity, from the “spectre … haunting Europe” in The Communist Manifesto to the “vampire life” of capital in Das Kapital.

Developed in part as a reactionary response to the revolution in France in 1789, it can be politically radical. Patriarchal, yet polymorphously perverse, pared down and baroque, glamorous and gauche, the gothic is an aesthetic devised of opposing forces.

Songs of a Lost World could be seen as a return to the darkness of The Cure’s early material. Take the lead single Alone. The lyrics turn, thematically, on death and isolation. The music has the intensity and sense of glacial doom that speaks to the fatalism and claustrophobia common to novels such as Frankenstein and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, as much as classics from the “unholy trinity” including 100 Years and A Forest.

The song most clearly echoed in Alone, however, is Sinking, from The Cure’s shuffling, electronic masterpiece, The Head on the Door (1985). Both songs are lengthy and stately. They let the listener wait for most of their length before introducing Smith’s brief and despairing vocals. Despite the pared-down instrumentation of both tracks, the sound created has a density that calls upon the “wall of sound” production technique that defined The Cure’s most psychedelic and joyful recordings.

But this pulling between brightness and darkness, “the unholy trinity” and the pop excess of the other half of their catalogue, represents the band’s gothic heart. This is what makes Songs of a Lost World goth and The Cure goth too, whether Smith likes it or not.![]()

Neil Cocks, Associate Professor in the Department of English Literature, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.