Professor Lindy Grant, Department of History, reflects on the reopening of Notre-Dame cathedral after a fire destroyed parts of the building in 2019.

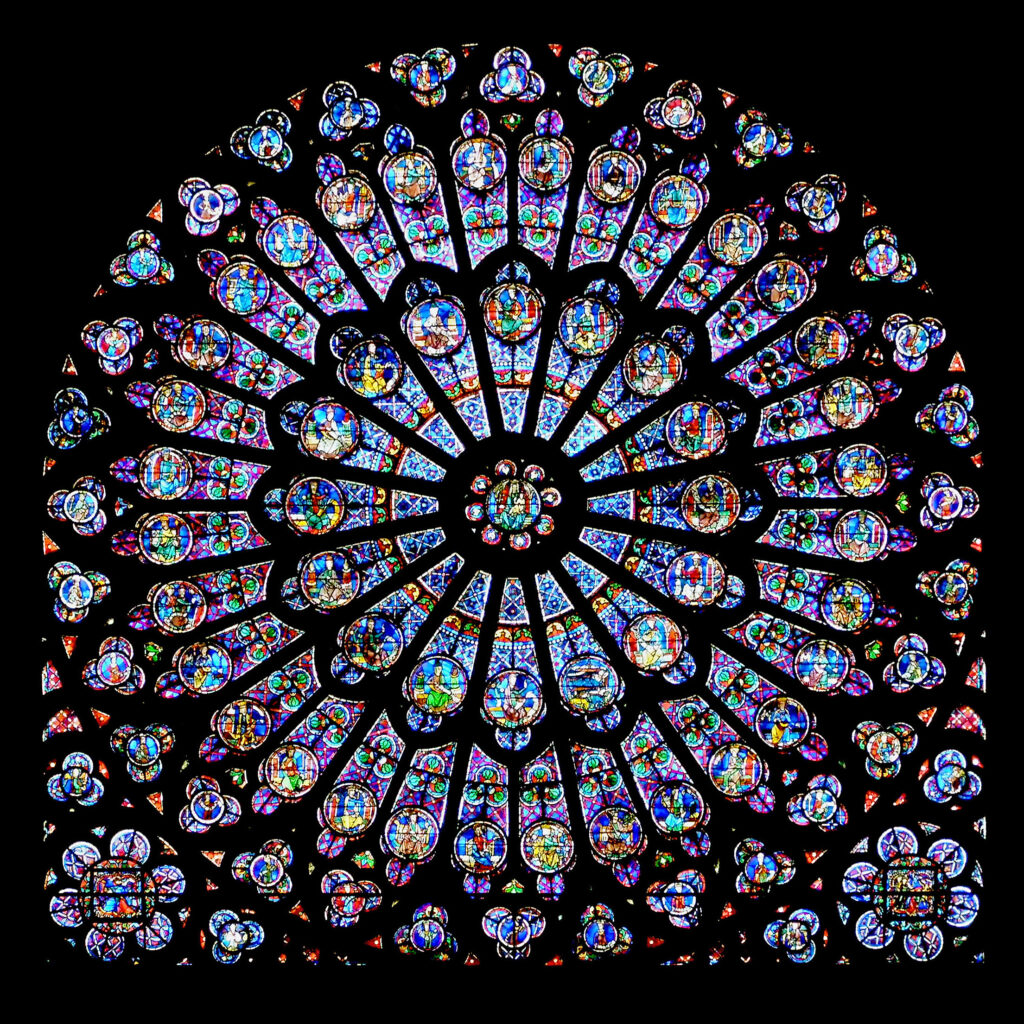

‘It’s so light’: that is what everyone has said about the cathedral of Notre-Dame, as it opened its doors again. It seems only yesterday that TV screens were filled with images of the cathedral roof ablaze, and the spire collapsing through the vaults. When President Macron announced that the cathedral would reopen within five years, it seemed an impossible task. There is still much to do, and a great cradle of scaffolding still enfolds the cathedral – but last weekend, its meticulously cleaned interior was revealed. The fire meant that everything was covered in a lead oxide dust, on top of the effects of candle smoke, pollution and a century and a half of dust, since Viollet-le-Duc finished his restoration of the medieval building in the late 1860s. Working in protective suits, conservators cleaned the stained glass with delicate brushes, and cleaned the stone with something like a face-mask – a thin latex glaze that could be peeled off taking the dust with it. Suddenly we can see the beautiful pale fine-grained Parisian limestone with which the cathedral was built.

When the cathedral was built, between about 1160 and 1260, the stone would have been covered with a light lime-wash, probably coloured with pale yellow ochre, onto which masonry joints would have been painted in white. At least that is what was found at Chartres Cathedral, built around 1195-1250, and in the nave at the Abbey Church of Saint-Denis, dating around 1260 or 1270. At Chartres, the yellow paint has been reinstated in a controversial restoration – controversial because the modern paint just looks too heavy. No original paint was found on the stonework of Notre-Dame, apart from the chapels added to the choir in the fourteenth century – and that paintwork, newly cleaned and fresh, was largely nineteenth century. So we can’t be certain that Notre-Dame had its pale ochre wash – but it’s likely. If it did it would have been like being inside a vast gold reliquary, with stained glass windows glowing like jewels against it.

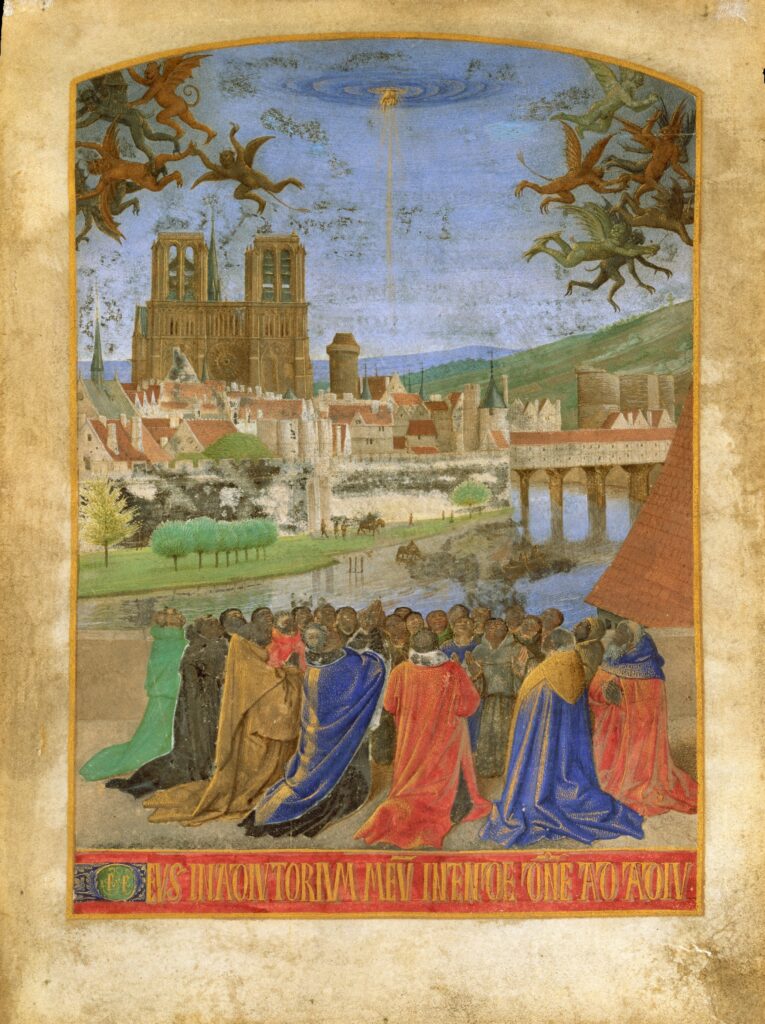

It’s ironic that light is the defining characteristic of the restored Notre-Dame, because light was a bit of a problem from the start. When it was begun, around 1160, Notre-Dame towered above its contemporaries. It was close to 100 feet to the vault: the cathedral of Laon in France, or the choir of Canterbury Cathedral in England were approximately 75 feet to the vault. In 1177, the Norman chronicler, Robert of Torigni, Abbot of Le Mont-Saint-Michel, declared the new choir of Notre-Dame the most beautiful church north of the Alps, though it didn’t yet have its roof. But by the early thiteenth century, as the choir of Notre- Dame was finished, and work progressed on the nave, a new clutch of cathedrals, notably Chartres and Bourges (which is Notre-Dame on steroids), were not only taller, but had huge upper windows to provide direct light into the church, filtered only through their rich stained glass windows. The builders of Notre-Dame struggled to keep up, rebuilding the upper walls of the cathedral with bigger windows. But unlike the slightly later thirteenth century buildings, Notre-Dame had a gallery – a sort of first floor aisle – which darkened the interior. In the eighteenth century, Notre-Dame was brightened up considerably – but by the drastic expedient of removing all the stained glass, except in the rose windows and in some of the chapels. A terrible loss – but they would probably have been severely damaged in 2019 when the roof burned. And now the meticulous post-fire cleaning has given the interior of the cathedral the luminosity that its medieval architects tried so hard to provide.