Vicki Harman, Professor of Sociology at the University of Reading and co-investigator of the Doing Porridge research project, sheds new light on the impact of food in women’s prisons, showing how it affects identity, dignity, well-being, rehabilitation and even social relationships.

Food is rarely seen as a critical part of the prison experience or common debates on prison reform. But for women in prison, food can be a lifeline or another form of punishment. The Doing Porridge research project aimed to analyse the experience of food in women’s prisons using an intersectional approach. The study captured the voices of 108 women across four prisons using a range of methods including observations, focus groups, diaries, art-workshops and semi-structured interviews with 80 women. Through those methods, the project aimed to understand women’s experiences of food in prison and inform changes in policy and practice.

At a recent event in London, researchers, campaigners and prison leaders came together to discuss research findings and launch a new toolkit designed to help reimagine food policy in women’s prisons. What followed was a deeply moving and urgent conversation about inequality, exclusion and the power of food to nourish, heal and connect.

Food inequalities in prison

Food provision varies across different prisons. Research participants felt that being in an open prison afforded them more consistent access to quality nutritious food compared to being in a closed prison. However, even within the same prison, not everyone has the same experience when it comes to food. Women who can’t afford to buy extras from the prison canteen* rely solely on basic prison meals which are often perceived as carb-heavy, poorly cooked and served at awkward times. Others supplement their diet with snacks or self-cooked meals, but only if they have the required access to food-preparation resources and skills.

Eva, a participant in the research, described how financial inequality limits access to even basic food comforts: “If you were someone that didn’t have money sent in or you weren’t working in the prison… food would be even more horrendous because you can’t make it better by adding stuff to it.”

Cultural identity and the prison menu

Food has a strong connection to identity, tradition and respect. The lack of those connections reinforces exclusion. Many women in the study spoke about feeling invisible when it came to food that reflected their background. Some felt that dishes reflecting their cultural or religious heritage were generally only served during events like Black History Month, if at all.

Katie Fraser, Head of Practice at Women in Prison, explained how cultural barriers to food deepen inequalities and hinder rehabilitation: “Food policies that ignore culture also ignore people’s sense of self. For women already marginalised by the justice system, that lack of recognition adds another layer of harm.”

Mental health, trauma and the healing power of food

Food isn’t just a form of sustenance – it can heal, harm or trigger painful memories. The research team heard from women with histories of domestic abuse, eating disorders and food insecurity. Some refused to eat prison food out of fear or mistrust. Others described consuming sugary snacks like chocolate bars to help bridge the gap between breakfast (commonly served the evening before it is intended to be consumed) and lunch.

Actor Jen Jo from the Clean Break Theatre Company, spoke from lived experience about the emotional impact of food deprivation and the sense of control food exerted over daily life in prison: “Being on the inside, food felt like another way to control you. You were always hungry, always anxious. It wasn’t nourishment – it was just something to get through the day.”

Lucy Vincent, Director of Food Behind Bars, discussed the value of giving visibility to women’s voices. She also explained that while budget constraints are a reality, food in prisons doesn’t have to be poor quality. She emphasised the importance of staff training and cross-prison collaboration to share best practices: “If we want better food and better outcomes for women, we need to invest in staff – through proper training and spaces to share what works. That’s how we build confidence, consistency and care across the prison system.”

Family connections: Rebuilding bonds through food

The research also explored the role of food in relation to family relationships in the space of the prison visiting room. Visiting rooms provide an opportunity to connect with family through food, yet restrictions and lack of choice make this difficult. Helen Blasdale, from the Prison Advice and Care Trust, emphasised the importance of food in maintaining family ties during prison visits: “Sharing food is one of the simplest, most powerful ways families connect and that shouldn’t stop at the prison gates. A cup of tea, a favourite meal – those small things matter.”

She noted that for many families, shared meals create a sense of normalcy and connection. The study also highlighted how women felt the range of food available could be increased. Kate, a participant in the research said: “For the breakfast, for the children, for the early visit, I said you need to get some breakfast options, whether you get a toaster or something behind and I can just make them a slice of toast with some jam or something or the pots of porridge, where you just add the water to, just so they’re having something, rather than having crisps”.

A toolkit for change

Building on the experiences of women captured in the research, the New approaches to women-centred food policy and practice in prison toolkit is designed to be a practical resource that can drive real change. It provides specific, evidence-based recommendations on improving food policy and practice across the women’s estate, including:

- Diversifying menus to reflect cultural and religious needs all year round

- Improving food scheduling to mirror real-life routines

- Expanding self-catering options to promote dignity and skill-building

- Strengthening governance by involving women in decisions

- Supporting staff through training and shared best practice

This project has highlighted the important social role of food in the unique space of women’s prisons, and the connections to family relationships beyond prison. The research team is delighted that the launch of the toolkit was able to create dialogue about prison food routines, governance challenges and practical opportunities to improve food in women’s prisons.

Food in prison is about more than just sustenance – it is about dignity, identity and the possibility of a better future. By taking these insights forward, policymakers and practitioners have the opportunity to make meaningful changes that will improve the lives of incarcerated women and support their successful reintegration into society.

Coming soon is a second part of this blog in which Professor Vicki Harman will discuss her experience of communicating the research findings thorough the creative process of filmmaking and how that helped amplify the voices of women behind the prison walls.

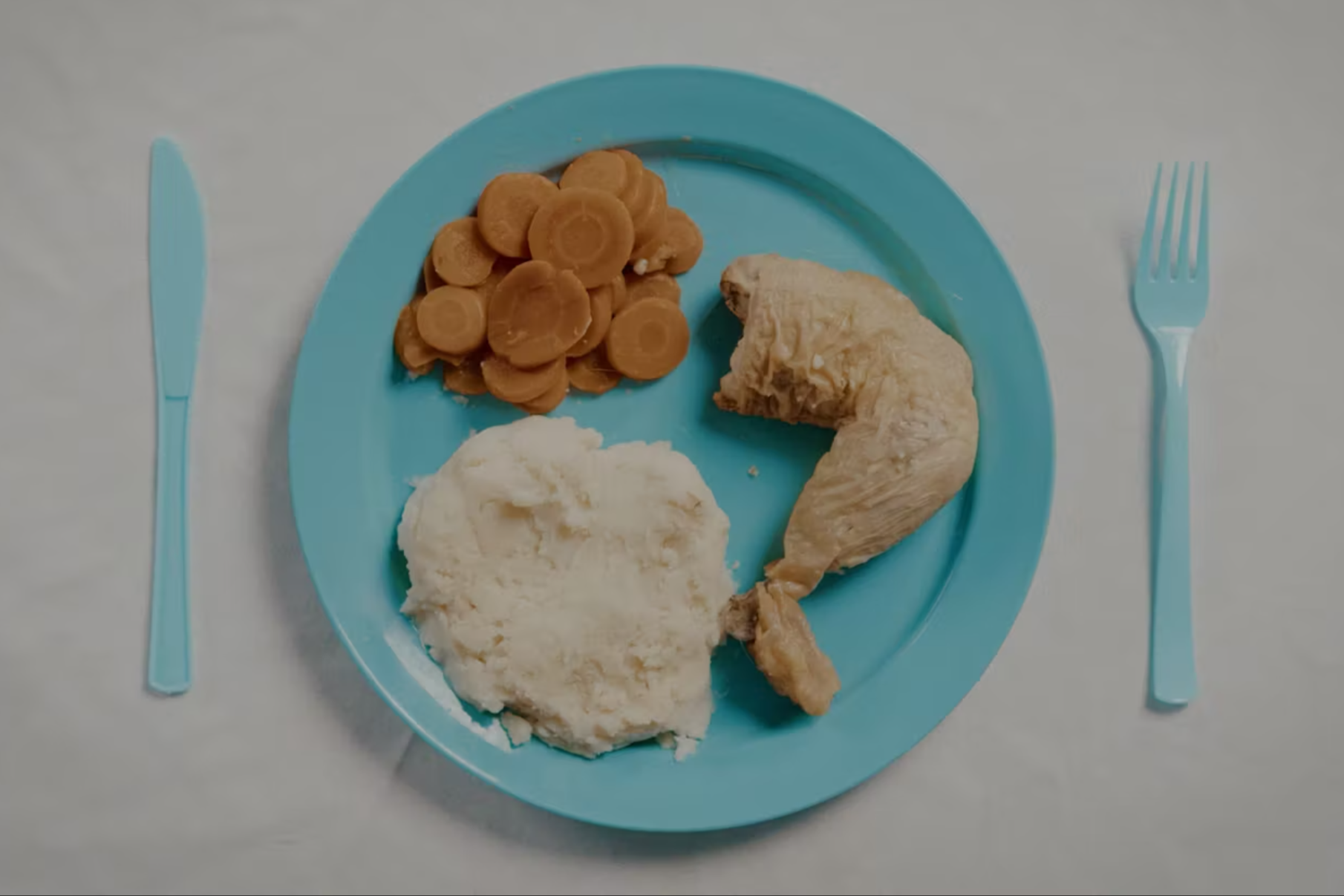

Cover image: Screenshot from the film Doing Porridge: Understanding women’s experiences of food in prison, directed by George Magner, Mountain Way Pictures.

[*] Canteen is the term used within prison for the weekly order of items that people can buy for themselves by filling out a paper sheet. The choice is limited to basic treats such as chocolate or biscuits.