Kathryn Murphy, Data Scientist on the REMADE project, explains how the changing silver content of ancient coins tells a tumultuous story of political upheaval in the third-century Roman Empire.

In 274 AD, almost 55,000 coins were placed in a lead box and a large ceramic jar, and buried in a field at Cunetio, in what is now Wiltshire. The coins lay undiscovered for 1,800 years, until they were unearthed by metal detectorists in 1978. The hoard is one of the largest ever found in Britain.

Coins may be small, but they provide a significant amount of information – even when viewed with the naked eye. They have two images – usually a ruler or other identifiable person on the ‘obverse’, and another image on the back or ‘reverse’. This might be a deity, or something that commemorates a specific victory or event. The text, or ‘legends’, on both sides provide more descriptive information, and there is sometimes a date or a mark to identify the mint where the coin was struck.

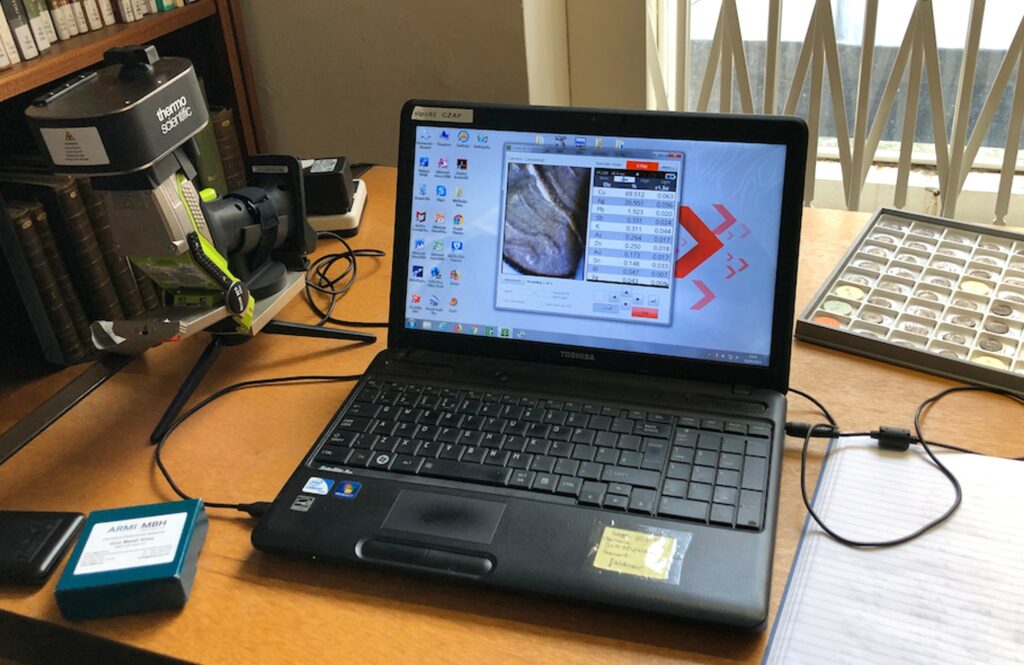

But closer inspection of the kind being done by the Roman and Early Medieval Alloys Defined (REMADE) project uncovers even more secrets. The team is analysing the chemistry of Roman copper alloy coins, and thousands of other artefacts, to reveal information about how they were made and the people who made them. The project uses portable x-ray fluorescence (pXRF), a technique where high powered x-rays are used to determine the chemical elements that an object is made of, without causing any damage to the artefact. The coins from the Cunetio hoard are a key case study for the project.

The divided Empire

Coin specialists, called ‘numismatists’, have studied the Cunetio coins, revealing a great deal of information about the Roman Empire in the mid-late 3rd century. This was a very tumultuous time, now known as the Crisis of the Third Century. At least 26 people claimed the title of Emperor during this period, and the Empire twice split in two.

In 260 AD, Postumus, a general in Germany, rebelled against Rome. He created a new, breakaway empire made up of Germany, France, Spain and Britain – known as the Gallic Empire. Meanwhile, Emperor Gallienus was ruling over the main, Central Empire. He had dealt with numerous invasion attempts and rebellions during his reign, but he could not suppress Postumus’ rebellion, and he lost control of the western empire.

Both Emperors were eventually assassinated by their own men – Gallienus in 268 AD and Postumus in 269 AD. In both Empires, there were then several more Emperors and further attempted rebellions. Eventually, General Aurelian became Emperor of the Central Empire, and Tetricus I became the emperor of the Gallic Empire. In 274 AD, Aurelian marched from Rome to northwestern France, and there was a bloody battle between the two empires. Aurelian was victorious. Tetricus I surrendered, and Aurelian reunited the Roman Empire.

During this period of the Roman Empire, the main type, or ‘denomination’, of coin in circulation was what we call a ‘radiate’. This name is based on the spiky ‘radiate’ crown that the Emperors are depicted wearing on the coins.

These coins were originally made of about 50% silver and 50% copper alloy before the crisis. By the time of Postumus’ rebellion, the radiate coins had become extremely debased, and they only contained about 1% silver. They were now essentially copper alloy coins with a small amount of added silver. The devaluation of the coins meant that tens of thousands of coins had to be produced in the mints every day to ensure there was enough supply of money to pay the Army and keep the economy going.

A story in silver

So how is REMADE linking the political upheaval and rebellion to the chemistry of the Roman coins? With this history and the detailed coin studies in mind, the team analysed 1,500 coins from the Cunetio hoard. Groups of coins for each of the Emperors of the Gallic and Central Empires were selected for pXRF analysis. Since there is a date for each coin, the chemical results for each coin can be put in order and changes over time can be tracked.

When Postumus rebelled and formed the new Gallic Empire, one of the first things he did was increase the silver in his coins back up to around 30%. Postumus knew that he would not be able to stay in power for very long without the support of his soldiers. The decision to increase the silver in Postumus’ coins was made to get the Roman Army on side and keep the soldiers happy in his breakaway Empire.

Prior to the split in the Empire, Gallienus had been able to increase the silver in his radiate coins to around 25%. When the rebellion took place, Gallienus not only lost control of territory; he also lost access to the majority of the Roman Empire’s silver mines. This meant that Gallienus was no longer able to add additional silver to his coins, and the silver content dropped down to less than 5%.

But Postumus was only able to maintain the high silver content for a few years. By the time his reign came to an end, his coins contained 5% or less silver. None of the other Emperors of the Gallic and Central Empires were able to improve the coins, and the silver content stayed below 5%. Once Aurelian reunited the Empire and political stability returned, he was able to restabilise the economy by undertaking massive coin reforms. Aurelian kept the radiate coin but increased its value, and brought in new gold and silver coins.

In addition to being able to track the silver content, by examining the levels of other elements in the coins we can see that each Emperor had a specific metal recipe that was used in their coins. These recipes were distinct from each other, and were very tightly controlled. Coins minted in different parts of the Empire, and over many years, maintained the recipe for each Emperor. These metal mixes reflect each Emperor’s access to resources, the economic situation, and underlying political motivations.

This is just one story that has been revealed through the chemistry of Roman coins. Working with partner organisations across the UK, REMADE has analysed around 10,000 artefacts and coins, with plans to analyse thousands more by the end of the project. Every day, the team is uncovering more stories about the people and objects of the Roman and early medieval periods.

For more information about REMADE, visit the project website or follow on Bluesky for regular updates.