Winner of the Research Output Prize 2025 – Agriculture, Food & Health

James Ryalls, Senior Research Fellow in Sustainable Land Management, explains how air pollution disproportionately harms beneficial insects, threatening biodiversity and food security.

Imagine a world without the hum of bees pollinating flowers, or without tiny wasps keeping garden pests in check. These heroes of nature are vital to our ecosystems and food security. They pollinate over 70% of global crops, contributing up to $577 billion annually to the global economy, and save farmers money by reducing the need for chemical pesticides. But an invisible threat is undermining their work: air pollution.

We’ve long known that smog harms human health, causing respiratory issues and heart disease. Plants suffer too, with pollutants like ozone stunting growth and reducing yields. However, the broad impact on different invertebrate groups has been unclear – until now.

In our recent study published in Nature Communications, my team and I revealed that air pollution hits economically beneficial invertebrates – including bees, moths and other pollinators – hardest, while pests often escape unscathed. This imbalance threatens biodiversity and food systems, even at pollution levels deemed “safe.” Recent studies suggest these effects are worsening over time, even as some pollutants decline in certain regions.

What we did

To understand air pollution’s impact, we conducted a meta-analysis – essentially a “study of studies.” We analysed 120 studies from 19 countries, including the United States, China and Australia, yielding 877 data points across more than 40 invertebrate families. We examined how key air pollutants, including ozone (O₃), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulphur dioxide (SO₂) and particulate matter (PM), affect invertebrates’ survival, reproduction, feeding and their ability to find food or hosts.

We grouped invertebrates by their roles and feeding strategies: for example, are they beneficial (pollinators, natural pest regulators or detritivores – nature’s recyclers that break down organic matter) or pests (chewing caterpillars or fluid-feeding aphids)? We also noted the plants they interacted with and pollution levels. Using advanced statistical models, we calculated performance changes in polluted versus clean air, ensuring robust results by accounting for study biases.

Key findings – beneficial bugs bear the brunt

Overall, air pollution reduces beneficial invertebrate performance by 31% compared with clean air. Pollinators like bees, natural pest regulators like parasitoid wasps, and detritivores see drops of 21–39%. Their searching efficiency, crucial for finding flowers or prey, drops by a third on average. In contrast, pest performance remains unchanged or even improves slightly for some groups – for example, borers (insects whose larvae tunnel inside plant stems and roots).

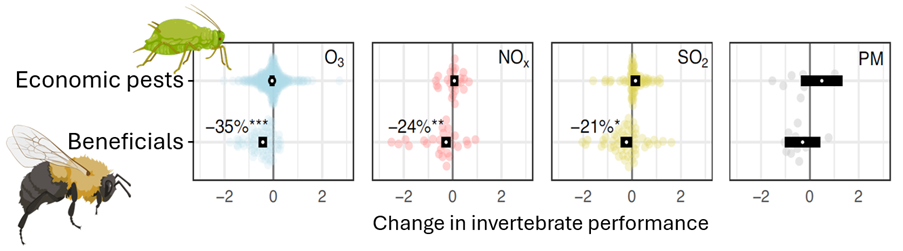

Breaking it down by pollutant, we found that:

- Ozone (O3) is the worst offender, reducing the performance of beneficials by 35%. Pollinators are hit hardest (42% reduction), likely by degrading scent cues (volatile organic compounds, or VOCs) that guide them to flowers. Alarmingly, these effects occur below the US Environment Protection Agency’s (EPA) 70 ppb “safe” limit, and global ozone levels are rising.

- Nitrogen oxides (NOx), emitted from diesel vehicle exhausts, reduces beneficial performance by 24%, severely impacting searching ability and survival. NOx from traffic quenches ozone in cities but persists in rural areas, worsening the problem.

- Sulphur dioxide (SO2), mostly from coal burning, reduces beneficial insect performance by 21% and diversity by 26%, though its effects vary widely, making patterns harder to pin down.

- Particulate matter (PM) shows no clear disproportionate harm, but data is limited, with only 58 data points, mostly from Australia. PM can coat plants or damage insect antennae, but more research is needed, especially in Africa and Asia.

Shockingly, even low pollution levels harm beneficial insects, suggesting current air quality standards fail to protect them. If ozone keeps rising as predicted, it could worsen declines already driven by habitat loss and pesticides.

The disparity in performance stems from differences in how beneficial insects and pests behave. Beneficials rely on volatile organic compounds (VOC) – scent chemicals that plants naturally release – as an ‘odour map’ to guide them in finding flowers to pollinate or pests to attack. Pollutants like ozone degrade these scents, leaving pollinators and natural enemies disorientated. Pests, often embedded in and protected by plants, are less affected and may even exploit pollution-stressed plants, which become easier to eat.

Implications and solutions

The decline of beneficial insects threatens food security. Fewer pollinators mean lower yields for crops like fruits, vegetables and nuts. Weaker natural pest control forces farmers to rely more on chemical pesticides, which harm our health and the environment. Air pollution, alongside habitat loss and pesticides, is a hidden driver of these declines, amplifying risks to biodiversity and agriculture.

The way to combat this is through policy, specifically stricter air quality controls. Reducing fossil fuels cuts all pollutants, but targeting O3 precursors (NOx and human-made VOCs) is key. Unlike the natural VOCs that guide insects to their hosts, these human-made VOCs from industrial and vehicle emissions worsen O3 levels when combined with NOx. However, reducing NOx may briefly boost O3 in some areas due to reduced quenching, underscoring the need for comprehensive emission cuts. Supporting policies like revisions to the U.S. Clean Air Act or EU emission standards will help.

Individuals can also help by adopting sustainable practices, like using public transport, installing solar panels, reducing car use, or planting pollinator-friendly gardens to buffer local effects.

While our study highlights air pollution’s bias against nature’s helpers, significant research gaps remain: we need more data on PM, pollutant combinations, and understudied regions like Africa and Asia. Future work should also explore how air pollution interacts with other stressors, like drought or heat.

Cleaner air benefits everyone – humans, plants and invertebrates alike. By acting now, through policy reforms, expanded research and everyday choices like reducing emissions and supporting pollinator habitats, we can protect these vital services. After all, a world with thriving bees, abundant crops and fewer harmful chemicals isn’t just sweeter – it’s essential for our future.

Read the full paper: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-49729-5

Cover image by Robbie Girling and Inka Lusebrink