Across millennia, people have buried objects alongside the dead. Ahead of his upcoming British Museum conference ‘Objects and death’, Dr Duncan Garrow spoke to Sarah Harrop about three mysterious things found in graves across time and what they tell us about the people who put them there.

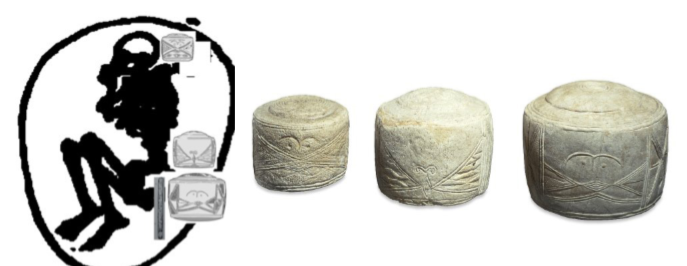

The Folkton Drums, North Yorkshire

“We always say they’re a bit like pork pies,” says Reading archaeologist Dr Duncan Garrow of the Folkton drums – a set of three squat, chalk cylinders found in North Yorkshire in the 19th century. The drums were discovered inside a barrow, placed around the remains of a child lying curled up on his side. They were made in the Neolithic (3,000 BC).

“The smallest is about the size of a small football. So they’re bigger than you’d have in your mind’s eye. They are almost unique, but the decorations on them echo the decorations that you get on pottery at the same time. But there are also these more enigmatic features – the lines and dots that could be eyes, or even other parts of the body – people have said all sorts of things!

“Because they were excavated in the 19th century, we don’t know as much as we’d like to about how they were located in relation to the body. But it’s very interesting that these very rare and unusual things were put with a child.

“In that part of Yorkshire chalk is a very important resource in the landscape. It may have had special meaning and could even have come to the burial from where the child grew up. You can imagine that being a kind of narrative that people are trying to place in the grave with the child,” he speculates.

With Dr Neil Wilkin from the British Museum and Dr Melanie Giles from the University of Manchester, Duncan leads the AHRC-funded Grave Goods: objects and death in prehistoric Britain project. The aim of the research is to transform our understanding of how people viewed death through study of the Britain’s prehistoric grave goods – which are renowned worldwide for their quality and craftsmanship.

Objects from burials have long been central to how archaeologists have interpreted society at that time. They can give us insights into personal identity and prehistoric life, yet they also speak of the care shown to the dead by the living, and of people’s relationships with ‘things’. As Duncan says, objects matter.

“Often with grave goods you get a very intimate insight into past people’s lives because you’re dealing with an actual body and an actual moment when people put things into a grave. But at the same time it’s very frustrating because you don’t know why they went in there or what they meant or how they related to that person that they were buried with. So it’s an interesting tension between that real intimacy and that complete lack of understanding.”

Duncan’s own theory is that the Folkton drums are communicating a message between the mourners and the child who was buried and that they are ‘animate’ objects: “They look like they could come alive. And they look like they are ‘clothed’ in those bandage-like decorations. I suspect that the decorations had some meaning because they are on the pottery as well – maybe in a very abstract sense that they would have understood but that we can’t really get to.”

As part of the Grave Goods project, a set of educational materials for schools have been developed by the team and three artists have been commissioned to create pictures relating to three sets of grave goods in very different styles – from Manga to a linocut.

Gold discs from the Knowes of Trotty, Orkney

The Knowes of Trotty are a big group of barrows or burial mounds on Orkney from the early Bronze age, around 2000 BC. Inside, gold and amber objects were found – unusual for burials in Orkney at this time.

Duncan explains: “This burial was particularly impressive because the grave contained these gold platings; the discs would have been put over something to keep their form. Similar gold finds have been found in continental Europe and Wessex. There are also amber beads, an amber lozenge-shaped object that was probably part of a necklace and so there’s quite a strong element of costume among the objects buried in this grave.”

But how did such exotic objects get all the way up to the wilds of Orkney?

“Orkney was – particularly in the Neolithic – a really important or vibrant place, really second only to Wessex and the Wiltshire area, where we find many of the most famous Neolithic monuments in Europe, let alone Britain,” Duncan explains.

“It was connected then in ways that we don’t think of Orkney being connected now. And this is a little bit of insight into those connections because you can draw lines out to see here the kinds of gold items in Portugal and Wales and those ones down there in Wiltshire. The amber probably came from Scandinavia.

“So in the early Bronze age you see networks developing that moved materials around the world actually in ways that you can’t imagine possible in 2,000 BC. They would have been carried on foot or by paddled boats, made out of skin. Or just down the line exchange, people handing things on from person to person. But presumably that person who put those things in the grave was in the midst of those kind of connections.”

The remains in the grave were of a cremation, so archaeologists don’t know the sex of the person. Artist Kelvin Wilson has echoed in his reconstruction image, where we see the a person of ambiguous gender wearing the gold discs.

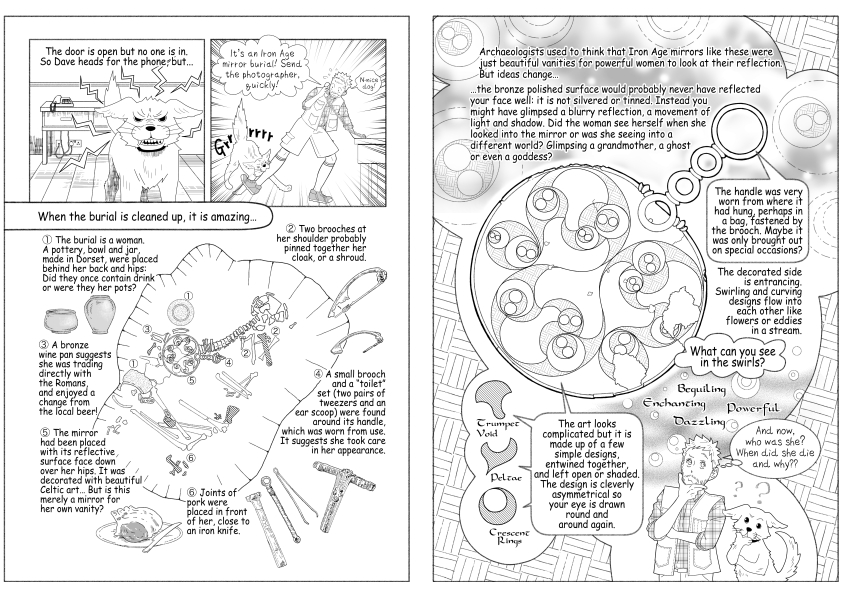

Portesham mirror, Dorset

“She had this amazing mirror buried with her, along with other things including bronze pans and imported Roman vessels and ceramic vessels as well,” says Duncan. “There were also joints of mutton and pork around the body, food offerings, suggesting food for the afterlife, or that they had a feast as part of the funeral process and maybe people were giving half of that funerary feast to the dead woman.”

“The mirror has this classic Celtic art decoration on the back of the mirror plate. When you see that you have to imagine it being not green but almost golden shiny bronze because it would reflect light a bit better. It’s possible that it was covered, it had a brooch around the ring that was maybe closing a bag around it.”

Mirrors were likely to have had a different purpose to today’s uses. Co-lead on the project Melanie Giles has written extensively about Iron age mirrors and theorises that that the quality of the reflection in the mirror as we would understand it is not so important as its power as an object.

“Really it isn’t about admiring yourself and checking out your beautiful face but about more than that – about seeing into the future, having special powers,” Duncan explains.

“Mel’s work suggests that it was thought that only that woman could control it and maybe it was buried with her for that reason, maybe it was so closely associated with her that it had to be put in the grave with her and nobody would come and get it out again.”

Manga artist Chie Kutsuwada was commissioned by the team to produce a cartoon telling the story of how the mirror was found – a tale of metal detectors, dog bites and digging in the dark:

Duncan relays the story: “After the metal detectorist found the mirror he did the right thing and phoned local archaeology unit – Wessex Archaeology – and an archaeologist called Dave Murdie was sent out to investigate. He realised it was a grave so he went back to the farm house to ring the boss to ask for more people to be sent out, as it was in the days before mobile phones existed.

He crept in a bit cautiously to use the phone and the farmer’s dog came up and bit his leg! Classically it was also found on a Friday so they had to dig it as it was getting dark, in time honoured fashion.”

Former Children’s Laureate and University of Reading alumnus Michael Rosen has written three poems about the objects featured in this post. He read them to children for the first time on 31 October 2019 at the British Museum. You can hear the poems in the videos below:

‘Objects and death: on the trail of grave goods’ took place at the British Museum on 31 May and explored how people have confronted, explained and come to terms with death through objects across time and around the world.

The Grave Goods project preceded a major partnership between the University of Reading and the British Museum established in 2017. A new collection storage and research facility: the British Museum Archaeological Research Collection (BM_ARC) is being built at Shinfield to house part of the Museum’s research collection. With a focus on global research, the facility and associated study rooms will give university students and academics access to the unique objects housed there.