On this World Book Day, I am reflecting on how my love of bookshops has informed my recent research. I am originally from the US and I worked in all sorts of bookshops throughout college and after – a chain retailer, independent, and second hand – and, for a time, I was surrounded by thousands of books on a nearly daily basis, but also the people and worlds they were linked to.

I attended bookshop-hosted events, including poetry readings, music sets, and performance art pieces. And I met all sorts of odd and interesting characters.

There was Paul, who wandered into my friends’ second hand shop and spun wild tales of living abroad (including in a castle) I didn’t believe until I bumped into him in a bookshop in Berlin years later; there was Mike, who had a rough go after a few decades in Paris, and who, while I assisted him in building bookcases for the independent we worked at, insisted I couldn’t go to graduate school until I read Moby-Dick; and Carolyn, who, at my first bookshop job at a chain retailer, quietly but insistently prodded me into considering a world of literature outside of the little corner of interests I then held.

Bookshops, in my formative years, brought together my university life, the literary and arts community, and all the readerly local characters of my hometown.

So, when I was researching my doctoral dissertation on modernist periodicals and learned that Dylan Thomas’s first book, Eighteen Poems, had been published by the bookseller David Archer, I had to know more about the seller.

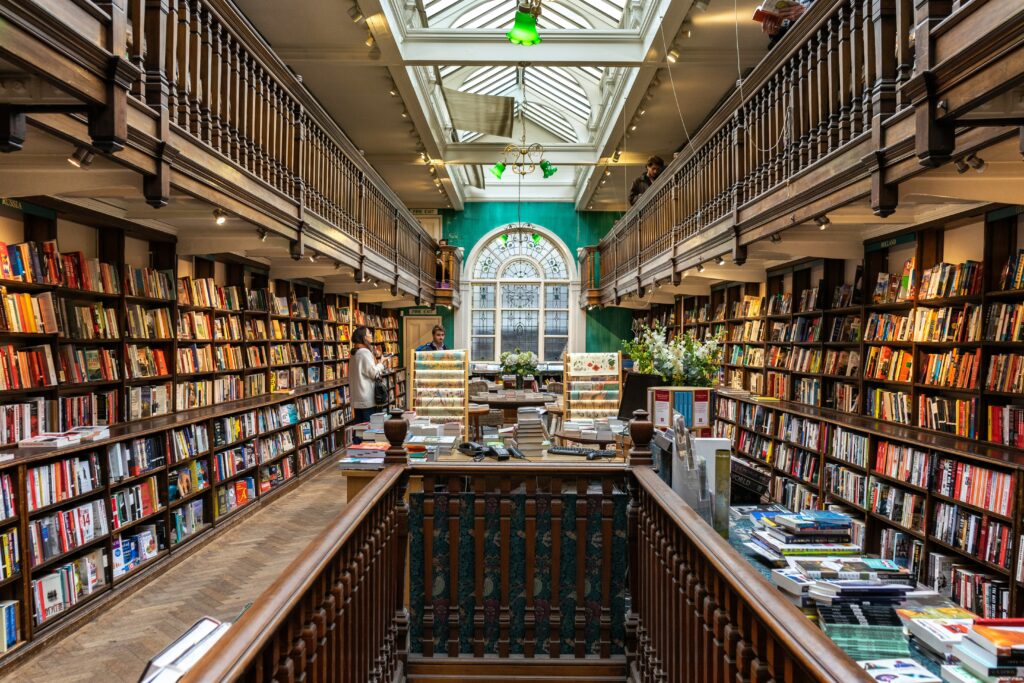

I wasn’t disappointed. Archer’s bookshop in 1930’s London, much like the independents and second hand shops I frequented, was more than a retail space – Archer published, housed, and otherwise aided his friends, the shop became known as a meeting-place, and occasionally a hiding-place, and for a brief time seemed to be the centre of all that was interesting in literary London.

It was with the publication of Huw Osborne’s The Rise of the Modernist Bookshop in 2015, where I was introduced to other booksellers contemporary with Archer, that I began to appreciate this cultural institution as a possible area for further scholarly inquiry. And presently, I am researching early twentieth-century booksellers who, like Archer, had some vital role in local literary, social, or political networks.

There is Sylvia Beach, who famously published James Joyce’s Ulysses in 1922, and whose Shakespeare and Company was a vital source of reading material for the expats and other visitors of interwar Paris.

Harold Monro opened The Poetry Bookshop in 1913 in London with an eye on providing a centre for all things poetry-related, and he published periodicals, anthologies, and broadsheets, as well as hosted regular readings at the shop.

Madge Jenison and Mary Mowbray-Clarke opened The Sunwise Turn in 1916, and Jenison’s memoir about the bookshop captures the eclectic world of literary and artistic characters they and their shop were involved with.

Yet, beyond these three, there were dozens, if not hundreds of bookshops adopting the model of the bookshop as more than a retail space at this time – a real centre for literary and artistic production.

And while today this form of bookshop feels increasingly rare, there are plenty of bookshops who publish, promote, or are otherwise engaged in their local communities: Five Leaves Bookshop (Nottingham), Book-ish (Crickhowell), New Beacon Books (London), and many, many others. (One valuable resource for finding more is the London Bookshop Map).

Finally, to note, there are also plenty of scholars similarly engaged and interested in bookshops – there is University of Reading’s own Centre for Book Cultures and Publishing and MAPP Project, as well as the Bookselling Research Network, formed in the UK but comprised of scholars and booksellers from around the globe. The research world of the bookish is large and largely friendly, and I am delighted to be a part of it in Reading.

Dr Matthew Chambers is a Visiting Research Fellow in the Centre for Book Cultures and Publishing at the University of Reading.