Winner of the Research Output Prize 2025 – Heritage & Creativity

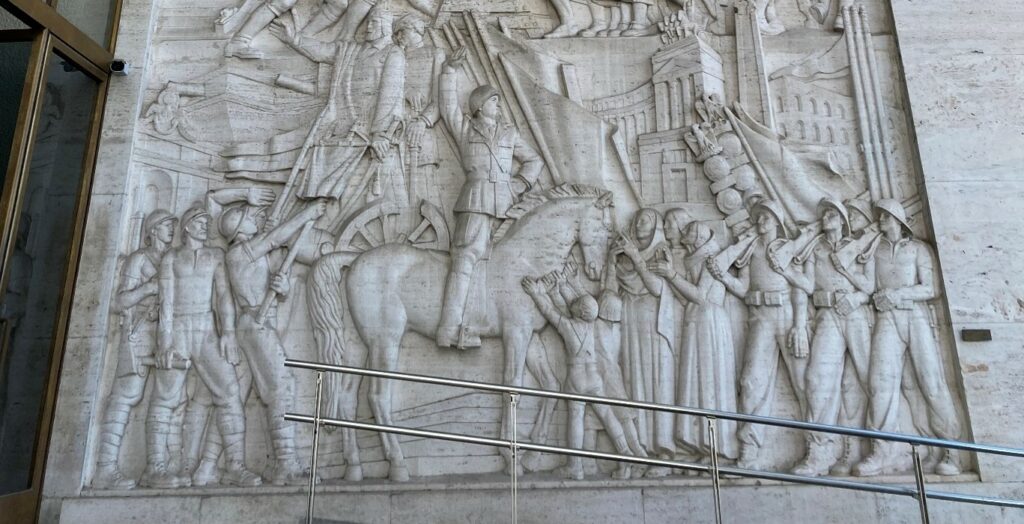

Samuel Agbamu, Lecturer in Classics, explains how modern Italy sought to legitimise its colonial ambitions in Africa by evoking the ancient Roman Empire.

When you think of the Roman Empire, what do you imagine? The massive silhouette of the Colosseum looming over the city of Rome, perhaps, or the straight roads that connected the ancient capital with the distant corners of its provinces? The well-drilled legionaries of its armies, marching down said roads to quell pesky natives – whether in far-off Britain or scorching-hot Palestine – rising up to gain their independence? Or maybe the traces of Roman culture left behind through the Latin language, underfloor heating or sparkling mosaics come to mind?

Whatever the Roman Empire means to you, the signs that ancient Rome has left behind an indelible legacy remain startlingly clear in contemporary politics and culture. To give a recent example, Elon Musk attracted controversy in early 2025 when he performed a gesture, which many interpreted as a fascist salute, but which his followers claimed as a “Roman salute”. Those who defended the gesture pointed to Musk’s claim that he thinks about the Roman Empire every day, as a way to distance his salute from fascism.

Yet throughout fascism’s history, it has been closely interlinked with ancient Rome. Elon Musk was not the first person to base his political visions on the empire of antiquity. In fact, since the collapse of the Roman Empire, countless leaders, states and empires have looked to it for inspiration. Perhaps no leader from history so aggressively cultivated associations between himself and ancient Rome as the Fascist dictator of Italy, Benito Mussolini. Mussolini, who came to power in 1922 and was killed in 1945, even went so far as to declare that he had re-established the Empire of ancient Rome.

In my 2024 book, Restorations of Empire in Africa, I trace the ways that the history of the Roman empire in Africa was used by modern Italy’s empire in Africa. This is a story that begins before Mussolini’s rise to power and ends long after his eventual fall, but which nonetheless reaches its most dramatic chapter under the Fascist regime.

The return of Rome

Italy is a relatively new country. It was only in 1861 that it became unified, and Rome itself was only absorbed into the new nation in 1871. Yet almost as soon as it became a unified nation-state, it embarked upon a project to become an empire. At the time of Italian unification, other European countries were carving out empires for themselves in Africa, a period of history known as “the Scramble for Africa”. If Italy wanted an empire for itself, therefore, it would be in Africa. Because ancient Rome had conquered vast swathes of North Africa, and because Rome was now in Italy, Italian imperialists claimed that North Africa was rightfully Italian since it had once been Roman.

On the fiftieth anniversary of Italian unification, Italy invaded the parts of North Africa which are today Libya. This invasion was startlingly modern, featuring the first bombing of a city by aeroplane. It was also a strikingly atavistic military campaign. As Italian colonial troops swept through the Libyan landscape, they were closely followed by archaeologists who excavated Roman remains as a way to prove the legitimacy of the Italian invasion. Italian propaganda from the time emphasised the links between ancient Roman and modern Italian imperialism. Part of this involved reviving ancient Rome’s characterisation of the Mediterranean as “our sea” – mare nostrum in Latin.

When Mussolini’s Fascist Party came to power, these links were even more aggressively promoted. In 1935, Fascist Italy invaded Ethiopia, committing war crimes on a genocidal scale which would, a few years later, be echoed in Europe. When the invasion was completed in 1936, Mussolini delivered a speech in which he declared that the empire of ancient Rome had been re-established – never mind the fact that Ethiopia had never been conquered by the Roman Empire. Tellingly, Mussolini’s speech was translated into Latin and disseminated widely.

The defeat of Fascist Italy during the Second World War and the formal loss of Italy’s African colonies following the 1947 Treaty of Paris did not end connections being made between the modern country and the ancient Roman Empire.

Migration in mare nostrum

In the wake of Western military interventions in the Middle East and North Africa during the so-called “war on terror”, the Mediterranean became one of the most dangerous routes for refugees seeking to flee war zones and enter Europe. One of the busiest routes was from Libya to the Italian islands of the central Mediterranean. In 2008, the then-Prime Minister of Italy, Silvio Berlusconi, made a deal with the dictator of Libya, Muammar Gaddafi. In exchange for preventing people from migrating northwards across the Mediterranean, Libya received the Venus of Cyrene, a Roman statue stolen from Libya by colonial troops during the 1911 invasion.

In 2011, on the centenary of the Italian invasion of Libya, NATO jets bombarded the North African country in an effort to topple Gaddafi. The conflict saw an upsurge in refugees attempting to cross the Mediterranean. Migration from Libya to Europe became an urgent issue after two ships, carrying hundreds of refugees, sank off the coast of the Italian island of Lampedusa in October 2013. At least 360 people died.

In response, the Italian government launched an operation to police the Mediterranean. They called this “Operation Mare Nostrum”, recalling not only ancient Rome’s claims to the Mediterranean but also modern Italian imperialism’s evocation of the Roman Empire. But now, mare nostrum was not about facilitating movement in and around the Mediterranean, but preventing it.

The transformation of mare nostrum from a tool of expansion to one of exclusion reflects a broader shift in attitudes towards – and debates about – migration. In the UK, the last two summers have seen explosive demonstrations of anti-migrant sentiment which have left me, the descendant of immigrants from Asia and Africa, feeling deeply unsettled. Restorations of Empire in Africa is a small contribution to the contextualisation of these current debates, not only in relation to histories of modern empires which continue to shape migration patterns, but also the ancient empires that have defined the imaginations of more recent imperialisms.