As part of the University’s Centenary Celebrations, a team led by David Stack in History has been researching the experiences of students and staff from working-class backgrounds at the University of Reading. Beginning with the widening participation roots of the University in the 1890s Oxford Extension movement and coming right up to date with policy recommendations for a more socially inclusive campus, the team have aimed to highlight working-class presence, celebrate success, and acknowledge ongoing challenges. Today, Jacqui Turner reflects on her experiences.

What does it mean to be working class? Let me add another layer to that: what does it mean to have a northern accent and be working class? And another: what does it mean to be working class, with a northern accent, and a woman?

Let’s start with the accent. In part it is a matter of time, attitudes have changed somewhat. However, even today the sound of a northern accent invariably provokes at least a moment of being considered less intelligent. A means of expression that is perfectly coherent but not quite in step with what is expected, marks you out as not speaking the ‘proper’ language of school, university and the professions. Of course it isn’t just northern accents, it is accents and expressions deemed to be working class, but with northern accents, especially Lancashire and Yorkshire, it’s the… ‘Sorry, can you repeat that I didn’t quite understand you?’

I was born in Lancashire at a time that unfortunately now appears as a topic or occasionally a module here in the History Department. I was brought up in a large, loving, political and very Northern extended working-class family. I was lucky enough to go to an outstanding girls’ grammar school and on to Manchester University in the early 1980s. After university I moved south and married a southern boy. I followed a career in marketing, completing my professional qualifications on the job at an earlier incarnation of Henley Business School, before coming back to university when my son went to school. But I came back to university a different person on the surface having lived in the south and worked in a professional job for many years.

My home and upbringing undoubtedly influenced my research, and I completed my PhD here at Reading. My thesis broadly considered the changes in the way that the working classes perceived themselves at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, predominantly in the North West of England, in and around Manchester. Two books led me down this path, Robert Tressell’s Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (1914) and George Orwell’s Road to Wigan Pier (1937).

There was a great deal I did not recognise in either book, unsurprising considering they were written almost a century earlier, but there were also some themes and vignettes that I did:

‘In a working-class home … comparatively prosperous homes–you breathe a warm, decent, deeply human atmosphere which it is not so easy to find elsewhere. I should say that a manual worker, if he is in steady work and drawing good wages – an ‘if’ which gets bigger and bigger – has a better chance of being happy than an ‘educated’ man.

Especially on winter evenings after tea, when the fire glows in the open range and dances mirrored in the steel fender, when Father, in shirt-sleeves, sits in the rocking chair at one side of the fire reading the racing finals, and Mother sits on the other with her sewing, and the children are happy with a pennorth of mint humbugs, and the dog lolls roasting himself on the rag mat – it is a good place to be in, provided that you can be not only in it but sufficiently of it to be taken for granted.’ (Road to Wigan Pier (1937), p.107)

Is this an overtly romantic image of working-class life by a middle-class writer who had never lived this life (no matter what his credentials)? Yes, it is. Is there an assumption that working men are barely educated or at least uninterested in the intellectual that completely misses the desire to improve your family’s lot in life? Yes, there is. But there is also something familiar, a security, comfort and sense of place that seeped into my childhood and spoke to the precariousness of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Tressell, an early working-class socialist writer, expressed frustration throughout his semi-autobiographical novel Ragged Trousered Philanthropists at the attitude that ‘if it was good enough for me its good enough for you [children]’, of ‘knowing your place’ in the hope of ‘getting on’ and earning a ‘decent wage’. That seeped through sometimes too. Not for me, thanks to my parents, but I heard it, especially towards men and boys, but altogether if you were the first or only one to ‘make the break’, to move on. If it all failed of course I was a woman, I could ‘settle down’ marry and have children, something that women were under more pressure to do. I remain the only person in my entire extended family who has ever been to university. There is something in this ‘first generation’ stuff.

What changed for me? It started when I went to my local girls’ grammar school in the days when no one was privately tutored to within an inch of their lives and at least some of the teachers spoke a little like me although others refused to speak to us unless we modified our speech. Doing well at school was essential, as was ‘not wasting your opportunities’.

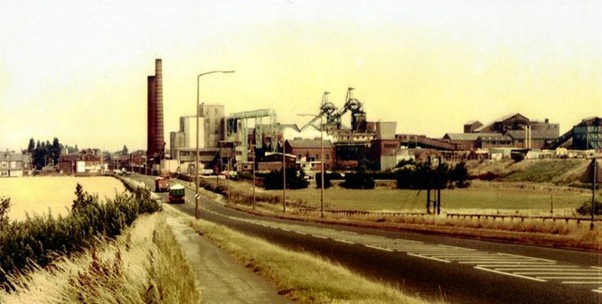

For girls, the threat of the Beecham’s Factory, the clocktower on the right, was where you would end up ‘making pills’ if you didn’t do well at school; downhill looking toward Pilkington Glass was where you could get a job as a secretary if you did OK, were polite, spoke properly and scrubbed up well. The brightest were encouraged to go to university, obviously to be teachers and others less keen on university into nursing. That was about it! Boys earned ‘good money’ in the colliery, often better money than a degree might bring, certainly in the short term. Otherwise, they needed to ‘get a trade’. For boys, it was all about potentially being ‘a good provider’ and financial security.

I did OK, and well enough to earn a place at university in the early 1980s. These were the days when we were lucky enough to get a ‘grant’, a means-tested allowance to support your time at university. My grant duly arrived but it did not nearly cover everything, certainly not rent after the first year. My family lived in a house with no central heating or double glazing and a kitchen in a lean-to with no heating at all (though what my mum produced while freezing in there was miraculous). Both of my parents worked ‘every hour god sent’ in blue collar jobs, so I lived at home and commuted into Manchester University working in Dixons Electric to try to cover my costs. Needless to say, it didn’t go well! I almost ‘settled down’. Almost.

I came back to university in my 30s, a very different person on the surface. In my early 20s I had taken Norman Tebbit’s advice and ‘got on my bike’, taken my dad’s advice too – ‘there’s nothing left for you up here’ – and moved south to fuel the burgeoning IT industry in the Thames Valley. But to do that I had to leave behind everything I knew, my family, friends and my cultural upbringing as I mostly moved into a world peopled by middle-class graduates with southern accents or who spoke a non-descript ‘estuary English’. I changed the way I spoke, not deliberately but gradually and inevitably. It was this change in the way I spoke that was the most obvious difference to my family in the north too. Why did I make the move? How had I done it?

As such, my desire to inspire my students stems from my own past. I am proud to call myself a feminist; life growing up in a northern post-industrial town meant I was surrounded by the political turmoil of the 1970s and 1980s before something changed for the better in the 1990s. I witnessed women becoming increasingly politically active, while my dad, an active trade union man through and through, encouraged me to engage with politics and never to be pigeon-holed by what I, or others, thought I could do as a woman. In terms of class, I also inherited his ingrained belief that ‘no one is any better than you’. My parents desire that I should have more opportunities than they ever had provided the bedrock for a self-confidence and resilience that working class kids needed and many young people from all walks of life, but especially working-class kids, desperately need today. However, it does also come with its own set of pressures.

Have I answered the questions I set out to at the start of this missive? Probably not and it isn’t all about accent; speech is just the most immediate factor. But my roots and indeed what I consider my cultural heritage, has shaped who I am and will always be. And I would not change it for the world.

Jacqui Turner teaches in the Department of History at the University of Reading.