Around 300,000 years ago, early humans were busy around a lakeshore in what is now a disused lignite mine in the town of Schöningen, Germany. The climate was cooling, and an ancient species of humans – possibly early Neanderthals – repeatedly visited this lake to hunt and then butcher animals. They mostly focused on large horses (Equus mosbachensis), but also hunted red deer, bison and aurochs. The wooden weapons they made and used at this lake for hunting were then discarded, sometimes because they were broken, and other times because they got lost among the tall reeds. What makes the archaeological site exceptional, and a focal point for understanding this period in human evolution, is that the weapons were rapidly buried in organic muds, beautifully preserving them until they were discovered during rescue excavations in the 1990s. Although early humans potentially used similar weapons to hunt throughout Africa and Eurasia, we rarely have the evidence of it, as typically wood rots very quickly.

Writing the biography of a long-lost tool

Over the next decades archaeologists recovered at least eight large wooden spears, and six double-pointed shorter weapons thought to be ‘throwing sticks’, thrown rotationally (a bit like a boomerang) at prey animals. Nearly 30 years after the initial discovery I led this publication, a detailed investigation of one of the throwing sticks, involving a team of experts at institutions in Hannover, Berlin and Göttingen. We applied an array of modern state-of-the-art imaging techniques, as well as a newly-developed terminology and recording system to illustrate the entire ‘biography’ of this weapon.

The double-pointed throwing stick. Photo credit: Volker Minkus, NLD

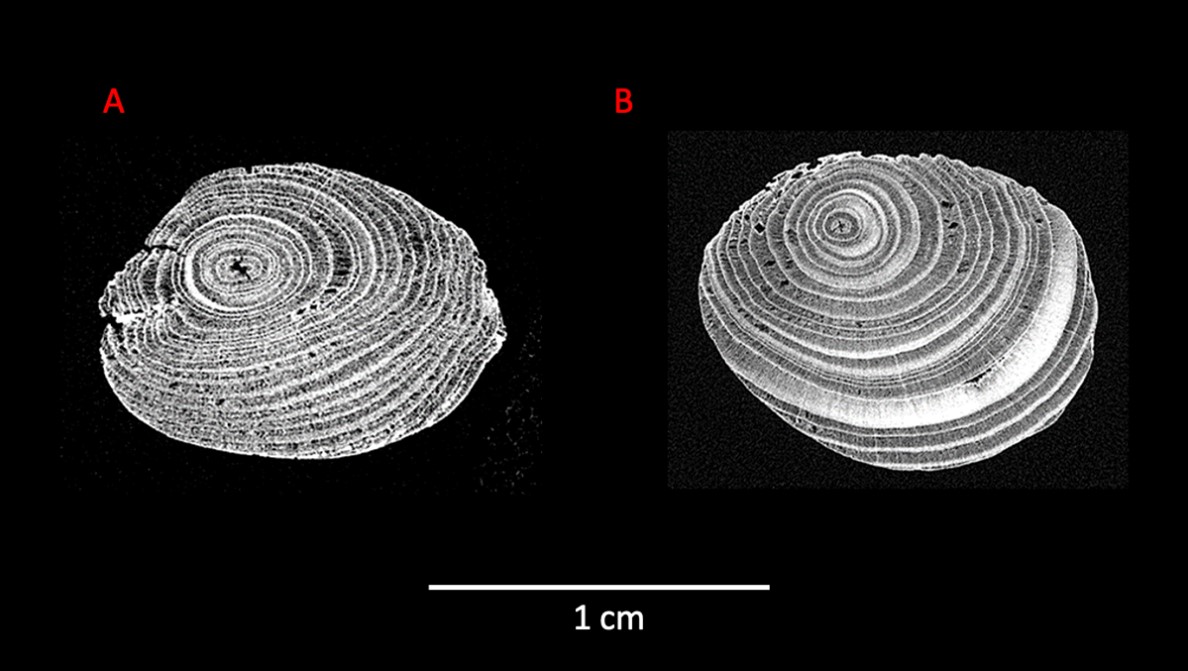

This biography begins with the initial selection of a branch of spruce, which would have been sourced somewhere away from the lake. The initial cutting of the branch was likely followed by seasoning the wood to prevent future cracking and warping. MicroCT scans showed not only how many annual rings the original branch had (representing 63 years worth of incredibly slow growth), but also exactly how the woodworker chose to shape the tool.

They used stone tools to remove the bark and then carve it and shaped the points so that the softest inner part – the pith – emerged not at the very tip of both points but to the side, making them stronger. It was uncertain whether the darker points involved use of fire, either to help shape the hard wood by charring it first or to harden the wood. Unfortunately our exploration of this question, using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, did not yet yield clear answers.

Micro-CT scans of both points.

An ergonomic and aerodynamic design

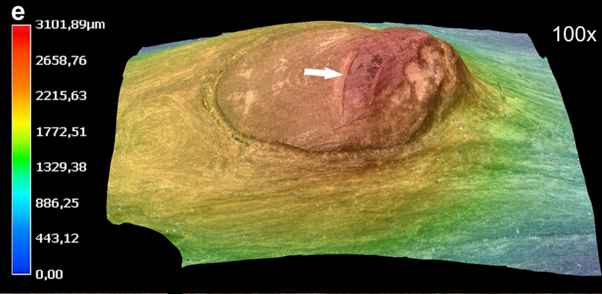

The weapon was crafted to be slightly elliptical in cross-section, which probably improved its ability to fly. 3D microscopic images illustrate different types of tool marks, helping us recreate their multi-step approach to woodworking. We could see mistakes, like a slip of the tool while removing bark, and also how they worked down knots to improve the ergonomics and aerodynamics. Finishing the tool probably included sanding to make it smooth, while a shiny polish around the middle shows where it was held, indicating a long period of use before being lost.

3D microscopic image showing the woodworking on one of the knots.

Finally, we mapped the effects on the wood after the humans lost this weapon at the lakeshore. For example, oddly shaped damage on this and other weapons at the site happened when hooved animals trampled on them, probably after they had been lying in the water for some time and had become quite soft. We made a detailed 3D model which allows us to share this tool more widely, which otherwise can only be seen on display at the Forschungsmuseum Schöningen.

A Neanderthal child’s weapon?

Recently archaeologists have begun engaging more in the lives of children in the deep past. We explore the possibility that a smaller tool like this may have been used by children involved in hunting. Among recent and contemporary forager societies, children begin playing with weapons in early and middle childhood, and usually learn to hunt larger game in adolescence. Throwing sticks are a type of weapon used by kids, alongside kid-sized bow-and-arrow sets and spears. Just like today, humans in the Middle Pleistocene would have needed to learn key skills early in life while their bodies and brains were developing. Shorter and lightweight tools like this provided good opportunities to learn key survival skills like how to throw with accuracy, and how to hunt different types of animals.

This study aimed to tell a story not just about the life of a weapon, but about the lives of those people who made and used them so long ago. The knowledge and skill around making seemingly ‘simple’ tools was rich, and highlights yet another way in which Neanderthals were similar to our own species.

Dr Annemieke Milks is British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Reading. Annemieke was awarded the 2024 Research Output Prize (Heritage & Creativity theme) for her article as co-author in PLOS ONE: ‘A double-pointed wooden throwing stick from Schöningen, Germany: Results and new insights from a multi-analytical study’.