The latest archaeological and geological studies are helping us discover more about Europe’s first ‘early human’ (hominin) occupants and highlighting how they coped with the practical challenges of life such as finding food and staying warm. In his new book Dr Rob Hosfield explains that early humans were more sophisticated than you might think.

H. heidelbergensis child and adult female (© Mark Gridley).

Living with the seasons

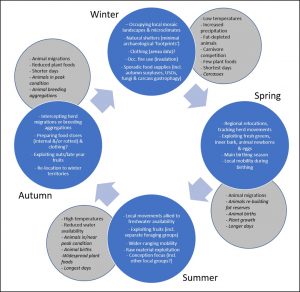

Ancient remains of small animals such as snakes, beetles and shrimp-like animals called Ostracods reveal that hundreds of thousands of years ago, early humans were mainly found in Europe during the warmer periods known as interglacials. In these periods summer temperatures were similar to recent, pre-industrial times, but with colder winter temperatures, especially in northern Europe.

Evidence from pollen and other plant remains, and bones from large animals such as horse and red deer, tell us that a wide variety of potential foodstuffs were available to people living at that time. Plant foods ranged from the green shoots of springtime to the nuts and fruits of summer and autumn; animal products included lean meat and fats, and organs including stomachs and brains.

By comparing these ancient records with wild foods available in modern ecosystems, such as the Białowieża Forest in Poland and Belarus, we can see how the availability and quality of foods would have fluctuated through the year. For example, in late winter animals would be severely fat-depleted and in generally poor condition.

Rob’s research has identified four critical ‘moments’ in the early human year:

- the depths of cold winters

- the spring renewal of plants and animals

- the bountiful foods of late summer

- the autumn concentrations of breeding animals.

So in light of these seasonal fluctuations in weather conditions and food resources, just how did Europe’s earliest humans keep safe and warm, and fed and watered, 1.6 million to 300,000 years ago?

Clothes and shelters

Archaeological evidence suggests that to survive cold winters early humans wore animal skins (probably un-tailored) and used natural shelters, such as spaces under fallen trees, to stay warm, rather than being reliant on humanly-produced fire.

Fossil evidence, particularly tooth growth rates, suggest a relatively long childhood, and it seems likely that children, as well as adults, were involved in springtime foraging for newly available plant and animal foods. Such foraging would continue into the summer months, but those longer days may also have been a critical time for older children to observe and practice the skills required to survive in ‘ice age’ Europe.

Autumn would see people drawn towards congregating animals, such as deer ruts, and likely resulted in encounters between different human groups, each made up of a few people, which provided opportunities for sex and reproduction with social and genetic strangers.

Archaeological and geological records are therefore helping us to build a clearer picture of the early human year, combined with insights from modern ethnography and zoological studies. Rob’s new book adopts a novel seasonal perspective which also looks beyond the visible data to construct a viable picture of how early humans survived the challenges of the northern hemisphere and sheds light on the question of what sort of ‘humans’ these earliest Europeans really were.

Dr Rob Hosfield is a researcher in the Archaeology division. His new book ‘The Earliest Europeans — A year in the life: Seasonal survival strategies in the Lower Palaeolithic’ is available Open Access here and to purchase here.