In many ways the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us some valuable lessons about how we can do things differently in our towns and cities: homeworking, active mobility such as walking and cycling, reduced congestion and emissions, and better air quality (at least for a time) were all a direct consequence of the first 2020 lock down, and many people were able to enjoy parks and green spaces. But for others, such luxuries were few and far between as COVID exacerbated the real inequalities in income, health, and wellbeing we see in so many of our towns and cities.

Meanwhile the climate crisis remains and the declaration of climate emergencies across local authorities in the UK and globally have focused the minds of decision-makers and people in many towns and cities as to just how we can achieve the challenge of ‘net zero targets’, often by at least 2030.

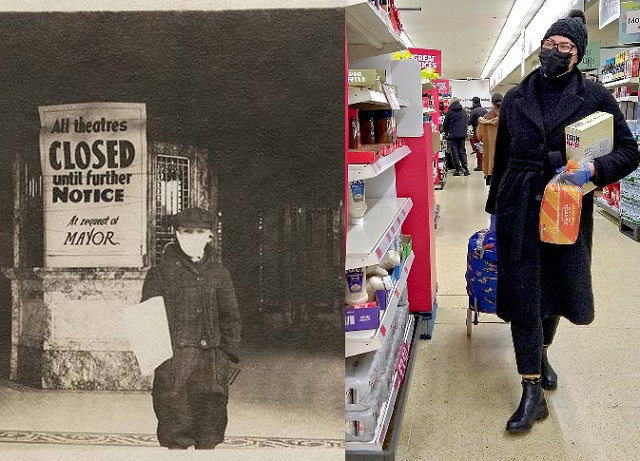

But what of the longer-term through to 2050? Many have questioned the future of our towns and cities by suggesting that they face an existential threat from COVID, climate change and other future, yet unknown, hazards. Although this might have some element of truth, cities have faced many threats in the past 4000 years (including pandemics such as Spanish Flu), but they have continued to bounce back and act as hubs for economic growth and centres for innovation and social learning.

So, rather than writing cities off, there are now even stronger and more powerful arguments for thinking that instead, we need to plan and think about the longer-term future of our cities much more strategically, and so overcome the potential disconnections between short-term political horizons and longer-term environmental change.

In my new book, with Professor Mark-Tewdwr-Jones of UCL, we explore how the concept of ‘urban futures’ can be used to develop city visions which are co-created. We define the concept of ‘urban futures’ as meaning to imagine what cities and urban areas will be like in the long-term, how they will operate, what infrastructure and governance systems will underpin and co-ordinate them, and how they are best shaped and influenced by their primary stakeholders (civil society, governments, businesses and investors, academia and others).

Urban futures thinking requires city stakeholders to work together in terms of co-creating a city vision in a highly participatory way. This means that four main groups (civil society, local government, business and academia) need to work together to build and develop city visions, and as part of ‘urban futures’ thinking, city visioning is the formal process of creating a ‘city vision’, or a shared and desirable future for a particular city or urban area.

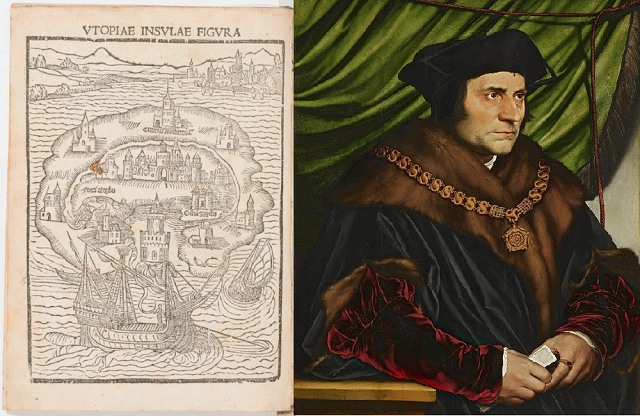

Thomas More’s Utopia

In the book we explore the history and evolution of city visions, placing them in the wider context of art, culture, science, foresight, and urban theory. After all, visionary thinking has been part of human culture, religion, and politics for many thousands of years. Visions are fundamental to thinking about the future and often related to preferred or desirable futures and to a shared sense of change and transformation. Early examples of what might be termed humanistic visionary thinking emerge in the writings of Plato (fourth century BC) and later on, Thomas More’s city-based Utopia (16th century). This sense of ‘futurism’ is also seen in the writings of Patrick Geddes and Ebenezer Howard, two of the early visionary planners in the late 19th/early twentieth centuries, who developed generic visions of what an ideal city should be.

Reading 2050 Workshop (Images courtesy of Reading2050 – a collaborative initiative, jointly led by Barton Willmore, Reading UK and the University of Reading)

The book also draws on my work with Reading 2050, and we also show how important futures thinking is in linking climate change strategy and sustainable economic growth (see for example the Reading Climate Emergency Strategy and the Reading Economic Recovery Strategy). It highlights and critically reviews examples of city visions from around the world including the UK (e.g. Newcastle City Futures), contrasting their development and outlining the key benefits and challenges in planning such visions.

Creating a coherent vision for a city is a challenging process, and requires resources, a clear plan and leadership. Thinking at city scale also requires thinking across boundaries, working with different interest groups, and using imaginative and innovative ways of engaging with communities. Cities will almost certainly survive just as they have done before, but in living with COVID and the climate crisis, we need to ‘fast forward’ the development of long term visions for our cities so that we can plan for smart, sustainable (and resilient) futures.

Tim Dixon is professor of sustainable futures in the built environment in the School of the Built Environment.

Urban Futures: Planning for City Foresight and City Visions is available from the Policy Press website.