Director of the Museum of English Rural Life (The MERL), Kate Arnold-Forster, reflects on a recent overhaul to transform a niche-interest collection of farming objects to a museum for all, exploring the link between land and people. Read on, and join Kate on 25th October, when she presents the next Reading 2050 lecture.

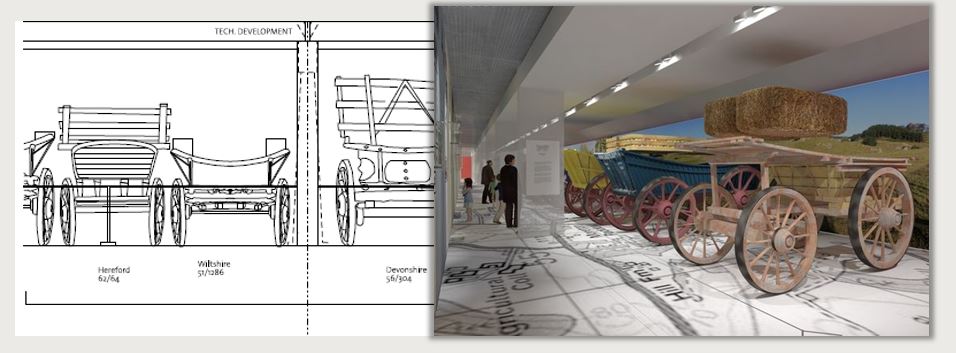

It is now almost two years since the Museum of English Rural Life reopened following a major capital redevelopment. We have created ten new galleries, re-displaying more than 20,000 objects. We have changed almost every aspect of the physical spaces that are accessible to the public.

The project took more than five years from inception to completion. For everyone involved – and this was a whole team effort – it is hard to exaggerate the importance of being part of this transformation.

For me, one of the both necessary and scariest aspects was taking the decision to change. We had to let go of what many valued and enjoyed about the old displays and how we presented the rural past. Yet for many reasons it was time to move on. We needed to re-frame the Museum not just physically, but in ways that would excite and inspire new, wider and more diverse audiences.

We wanted to re-engage with rural communities whose heritage is at the heart of the Museum. But our challenge was equally to change perceptions so that Reading people, in particular, would discover new ways of engaging with us.

As a museum dedicated to the history of English rural life, our project was about renewing our original purpose, but also about place-making on many levels: helping people identify with their own heritage and the rural places that mark their histories.

A key aim was to show how people lived and worked in the past and how this must inform the sustainable management of the countryside and its scarce natural resources for the future.

My forthcoming talk will reflect on the impact of the redevelopment: how new approaches to attracting audiences are shaping new forms of engagement for local visitors, including initial findings of the project evaluation and how we have changed as an organisation. Looking ahead to 2050, it will consider the future of the Museum in a changing social, cultural and economic context in contributing to Reading’s wider cultural regeneration.

The Reading 2050 project, including Professor Tim Dixon from the School of the Built Environment, has led to the development of a vision for Reading 2050 in consultation with local communities, organisations and business. Tim is hosting a series of public lectures to encourage debate on delivering the vision to ensure Reading can provide the jobs, living spaces and facilities that will allow us to enjoy Reading in a sustainable way.

Kate will give her talk on The MERL’s redevelopment on 25 October, as part of the Reading 2050 lecture series. Find out more.