Is Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book a simple allegory for colonial rule in India? Or is it about what it is to belong, and to be human? Ahead of her BBC Radio 3 talk to be broadcast during a Prom featuring music inspired by the book, Dr Sue Walsh provides her take on Mowgli’s famous adventures.

Some of the music to be played at the Prom on the evening of 20 August will be Charles Koechlin’s Les Bandar-log, a piece that was part of his nearly life long effort to set the whole of The Jungle Book to music. It’s for this reason that I will be taking part in a BBC Radio 3 Proms Plus talk on the subject, to be broadcast during the interval.

Imperialist relic?

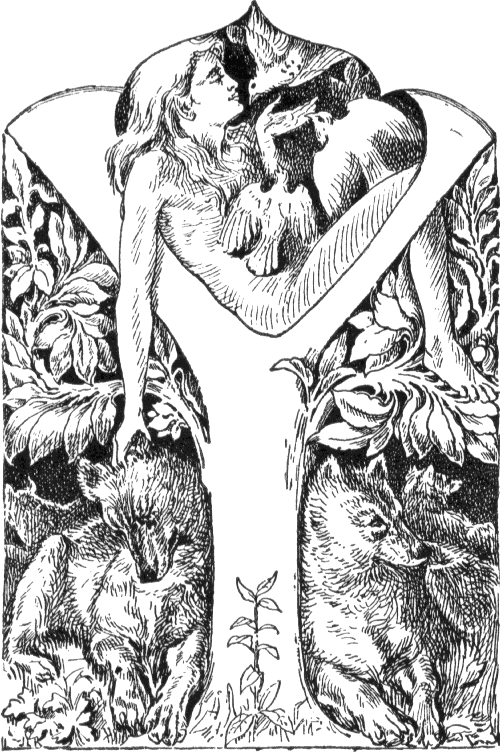

The Jungle Books themselves were first published in 1894 and 1895, and they feature stories about Mowgli, a boy raised by wolves in the Indian Jungle. The stories have remained popular, inspiring numerous adaptations, but their attitudes have been questioned by some parents and critics, who see them as a relic of Britain’s colonial past.

Indeed, a classic way of reading the tales is as an allegory for the position of the white colonialist born and raised in India, and Mowgli, the Indian boy who becomes ‘Master’ of the jungle, is understood to be ‘behaving towards the beasts as the British do to the Indians’ (as John McLure, author of Kipling and Conrad, interprets it).

This account, while persuasive in many ways, seems to me to be a bit reductive. It misses some of the interesting questions the stories raise about notions of belonging and identity.

The standard account relies on the idea that the human and animal identities within the stories are clearly distinguished from each other and fixed, and that this fixed distinction extends via allegory to ‘white’ and Indian identities.

Fluid identities

But what happens to our understanding of the stories if we don’t treat the human and animal identities within them as predeterminedly distinct? I would argue that a species name doesn’t necessarily fix identity. For example, Bagheera, the black panther, is described in terms of a series of other animals: he is ‘as cunning as Tabaqui [the jackal], as bold as the wild buffalo, and as reckless as the wounded elephant’.

Here then, attributes that are supposedly intrinsic to one animal can be found in another. This undermines any claim that those attributes are in fact the preserve of a particular species and it also implicitly undermines narratives of essential difference between species.

Also doesn’t a closer look at the relationship of the child Mowgli to the inhabitants of the jungle complicate accounts of the Jungle Books as straightforwardly imperialist in character?

Also doesn’t a closer look at the relationship of the child Mowgli to the inhabitants of the jungle complicate accounts of the Jungle Books as straightforwardly imperialist in character?

The eyes have it

Mowgli’s stare subdues the animal’s instinctual response and could be said to assert and fix a distinction between him and them. But Mowgli’s difference from Bagheera is written precisely not as an absolute difference from the animal, but as the difference between the expressed and repressed animal.

Bagheera the panther’s eyes convey exactly how he feels: they ‘blaze’ when he is angry. But Mowgli’s eyes, even when he is angry, are ‘like a stone in wet or dry weather’ and, according to Bagheera, ‘they say nothing’. Thus Mowgli is constructed as having a hidden aspect to him. He has the same emotions as the panther but these feelings are repressed and it is this that marks him as human. But it also means that at the heart of Mowgli there is the animal.

What’s more, the Jungle Book stories return to the issue of belonging over and over again, raising questions about the grounds on which one may claim to belong to a particular group or community: is belonging a matter of essence or of convention and social agreement?

All of these aspects of the stories lead me to feel that there is more to them than an imperialist narrative. In my monograph, Kipling’s Children’s Literature: Language, Identity and Constructions of Childhood I deal with all these questions and extend my discussion to a number of Kipling’s other books for children.

To hear Sue discussing The Jungle Book with Costa Book Prize winning novelist Frances Hardinge and New Generation Thinker Anindya Raychaudhuri, tune into Radio 3 at 17:45, 20 August 2019.

Dr Sue Walsh is an academic in the University of Reading’s department of English Literature. Her specialist interests include 19th and 20th century American Literature, post-colonial fiction and children’s literature.