TRT Project Blog #1 23.02.22.

Naomi Flynn reflects on the opening weeks of the Talk Rich Teaching project and gives readers a summary of how the team are working with schools to support teachers’ practice for multilingual pupils.

In this first blog for the Talk Rich Teaching Project I am reflecting on what has happened so far in the opening weeks of our research implementing The Enduring Principles of Learning (EPL). These principles have underpinned successful development in the US, for teachers in linguistically diverse classrooms, by changing teachers’ practice in ways that improve pupils’ academic outcomes. If, after reading this blog, you want to find out more about our project and The Enduring Principles of Learning (EPL), you can visit the other pages of our website https://research.reading.ac.uk/talk-rich-teaching/ .

In summary, we are working with teachers and children in four primary schools with high numbers of multilingual pupils to evaluate the potential for translating this US-designed approach to English settings. The project has two parts: a) my work providing professional development for the schools and teachers; and b) our PhD student Aniqa Leena’s project testing the children of teachers engaged in one-to-one coaching for the EPL and those of our control teachers. Our team includes Professor Suzanne Graham who is supporting the rigour and implementation of the testing. The project’s purpose is to support teachers with adapting their practice to maximise the social and academic well-being of their multilingual pupils, in ways that will also support the language and literacy development of all learners. It is a joint researcher and practitioner project in which we are learning from each other to find ways of making this US pedagogy one that works in English classrooms.

The Kindness of Teachers and Schools

Before I get to telling you how that is going, I need first to pause and reflect on the extraordinary kindness, generosity and professionalism of the schools and teachers working with us. This project started life in 2019 – in ‘the before times’. Schools committed to take part not only to support my practitioner research, but also to supporting Aniqa’s ESRC-funded PhD. Fast forward to the present and none of us would ever have guessed that we would be running the project in schools fighting the impact of a pandemic on all fronts. Teacher and pupil absence has affected our programme of professional development and the pre-project testing of pupils significantly. This has demanded remarkable flexibility and adaptability from everyone involved, and yet we are still all here and still standing. There are no words to express our gratitude to the schools and teachers involved in making that happen; the three experimental schools receiving professional development and the control school letting us use their teachers and pupils for a measure of ‘business as usual’. They are a tribute to the profession and demonstrative of its remarkable resilience and commitment to children’s futures. Thank you all.

Getting started with The Enduring Principles of Learning

I first got to know about the EPL through visits to the US state of Indiana where my colleague Professor Annela Teemant has pioneered their use with teachers in elementary, middle and high schools in several states. Working with her research team at Indiana University (Indianapolis) School of Education, Annela has delivered systematic professional development to many schools and teachers through a one-week introductory workshop in the school summer recess, and seven rounds of follow-up one-to-one coaching with individual teachers in the following academic year. She has found that this cycle of professional development has led to enhanced teachers’ practice, positive changes to teachers’ mindset for their multilingual learners, and improved school test results in language and literacy for both monolingual and multilingual learners. The improvements are greater for multilingual pupils. You can read more about my three-month Fulbright funded project, July – October 2021, learning about the EPL in detail from a series of blogs I wrote for NALDIC.

So far, our three experimental schools have received professional development at whole staff level, in which the Enduring Principles of Learning (EPL) were introduced. Alongside that, four teachers (2 x Year 1 and 2 x Year 4) have had me into observe their early experimentation with changes to practice using The EPL, followed by what we are calling ‘coaching conversations’. The post-observation coaching conversations match the model of professional development used by the US team who have already pioneered the EPL, but in practice our conversations are very much collaborative as we work out next steps together.

Alongside this professional development programme, the pupils in the experimental and control classes were tested by Aniqa before the programme started, and they will be tested again at the end of the summer term. Aniqa’s tests have been developed with the consent of the US test provider WIDA, and they measure pupils’ speaking, listening, reading and writing in English. They will tell us whether the professional development programme impacts on both multilingual and monolingual pupils’ academic outcomes. We also hope they will be teacher-friendly and could feed schools’ understanding of how best to assess multilinguals’ progress in ways that focus on what they can do rather than on what they cannot do in English.

Joint Productive Activity and Instructional Conversation

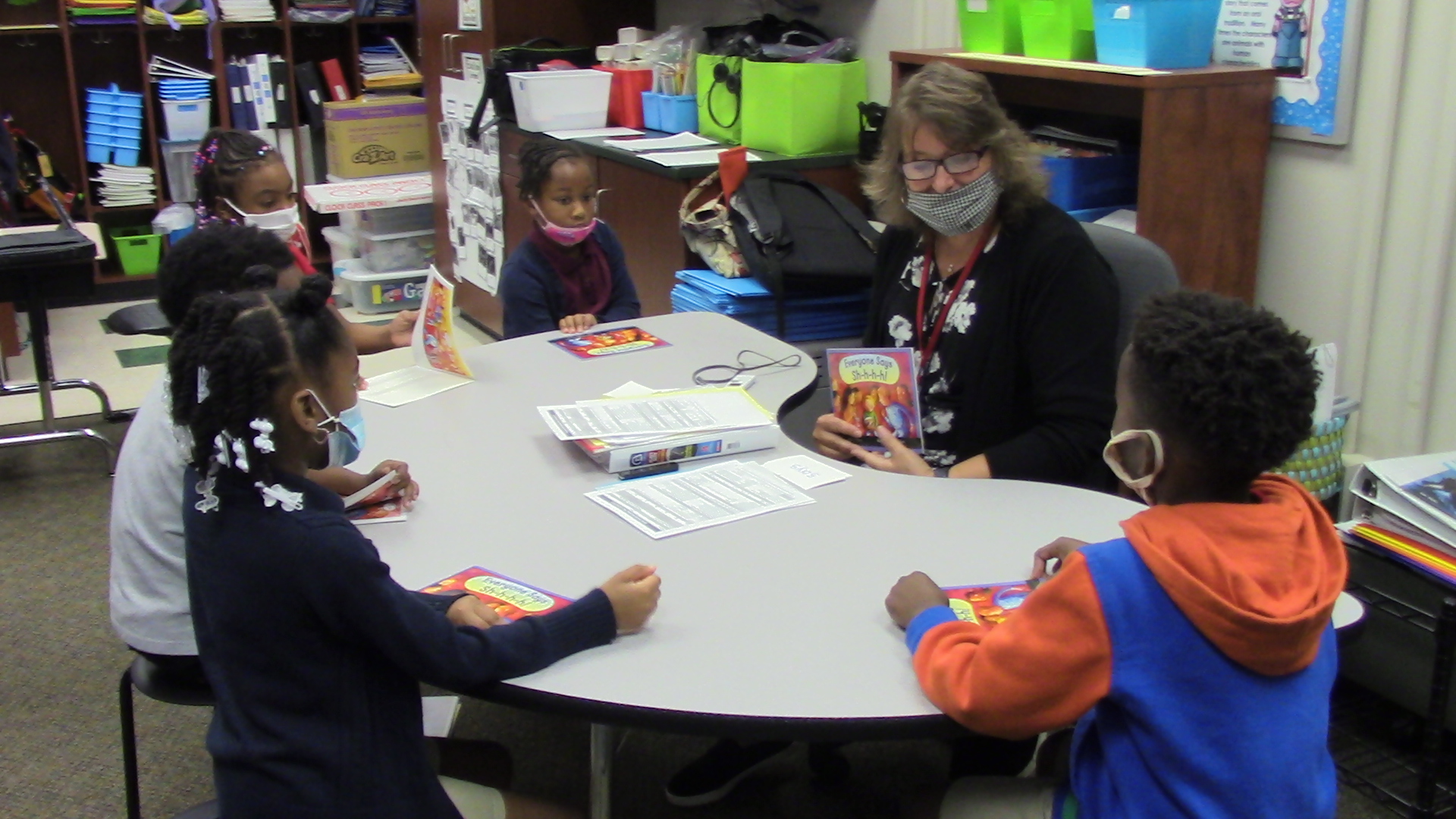

We decided early in the project that one of the key principles we would start with would be that of Joint Productive Activity (JPA). JPA is the first of The Enduring Principles of Learning and something of a driver for the rest because it requires that teachers work with small groups of learners for at least 10 minutes in concentrated dialogue; this towards an output which can be talk-based or concrete (e.g., written). It was the first principle that teachers I have observed working with the EPL in the US tackled, because this allowed them to focus on the mechanics of setting up small groups first. Whole class teaching has become something of a norm in English classrooms – particularly for classrooms in Key Stage 2 (ages 7 – 11 years) – and so our project teachers have been looking at ways in which they can operate small groups without too much change to what the children are used to. I’ll be saying more about this in our next blog.

In addition to JPA we are working to develop the principle of Instructional Conversation (IC). This principle focuses on how teachers have conversations with their pupils that prioritise pupil talk over teacher-talk. The teacher has a clear academic goal/ learning intention and uses the conversation to assess and assist pupils’ understanding through listening to pupil-pupil interaction and questioning pupils on their views and judgements. This is not something that is readily achieved by teachers more accustomed to whole class teaching, and so I am working with each of the schools to match the expectations of this principle to initiatives already part of school development. For example one school is working with Voice 21, another is using Talk Through Stories and the third is using the Let’s Think approach with young learners. So, in our March professional development meetings we’ll be observing some great US practice using IC, analysing the transcript of teacher versus pupil talk, and considering how this dialogue matches other talk-rich initiatives each school has up and running.

Interestingly, in all of the classroom observations tracked so far, the level and quality of teacher modelling is high and undoubtedly a driver for lesson success regardless of whether teaching is small group or whole class. While modelling is one of the Enduring Principles of Learning, it is not one we need to work at explicitly at this stage because this principle is already a well-honed part of the practice in the experimental schools.

Research into successful practitioner-researcher relationships tells us that projects work best where they grow from the schools’ own priorities. The Talk Rich Teaching project attends to the three experimental schools’ desire to raise their multilingual learners’ attainment while keeping in mind how this new approach can complement existing strengths. The joy of this project is that we are participatory – teachers and researchers finding out together how to make something work for the benefit of multilingual learners. We’ll let you know how we get on with further blog posts over the coming weeks and months.