by Dr Maria Ryan, Assistant Professor of American History, University of Nottingham

It has become a truism to say that Donald Trump’s political style is incendiary and divisive. While Trump did not create the United States’ longstanding economic, racial, and cultural divisions, he has fed and manipulated them like no other President in modern history. His scapegoating of the media/the Democrats/the Clintons/immigrants for the country’s political, social, and economic problems is reminiscent of fascism. Most recently, this toxic atmosphere resulted in the largest single mass murder of Jews in US history at the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, and the attempt to maim or murder 14 prominent critics of Trump through pipe bombs sent in the mail by a right-wing extremist and Trump supporter.

Yet in foreign affairs, Trump has been less impactful – at least in substantive policy terms. His aggressive rhetorical style has certainly brought American power into disrepute even amongst longstanding Western allies. However, as I argue in my contribution to Mara Oliva and Mark Shanahan’s edited collection, The Trump Presidency: From Campaign Trail to World Stage, Trump’s handling of foreign affairs in his first eighteen months had much more in common with Obama’s foreign policy than most Democrats or Republicans would like to admit – and more than might be expected given Trump’s domestic record.

Since summer 2018, Trump’s approach to the world has remained largely within the parameters of the post-Cold War mainstream US foreign policy tradition, and especially within the mainstream of the Republican Party. Even for some of Trump’s most controversial foreign policy decisions, there are significant precedents in recent history.

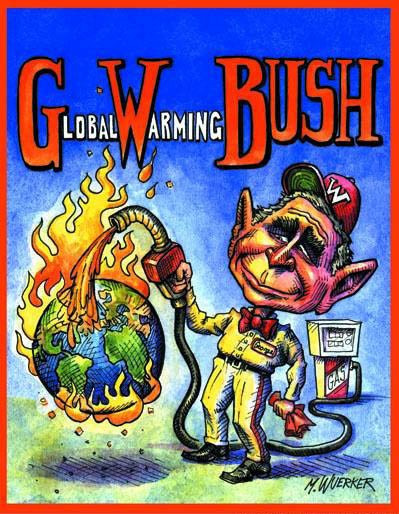

As regrettable as his withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement is, it is reminiscent of the Republican Party’s refusal to consider ratifying the 1998 Kyoto climate agreement, which – along with Clinton’s own reservations about the agreement, despite the fact that he signed it – meant the US never joined the accord. The George W. Bush administration rejected the science of global warming, agreeing only to selected non-binding emissions reductions in the 2005 Asia Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate. Rejection of the science of man-made climate change is a mainstream position within the Republican Party. This has hampered any attempts to tackle climate change at a global level, including the most recent effort by Obama.

Trump’s tariffs against China go against the grain of a gradual expansion of global free trade; but ‘free’ trade is not, and never has been, completely free. Protectionism remains integral to US foreign economic policy in certain areas, such as agriculture and sugar. George W. Bush imposed tariffs on imported steel from March 2002 – December 2003. Western economies developed through protectionism and despite the rhetorical embrace of free trade and the longstanding trend towards freer trade, we do not live in a world of completely free trade. Trump is unusual only in his open criticism of it, though this criticism was balanced, to some extent, by the signing of an updated version of the North American Free Trade Agreement – the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) – in October 2018, demonstrating that Trump was not opposed to pursuing freer trade.

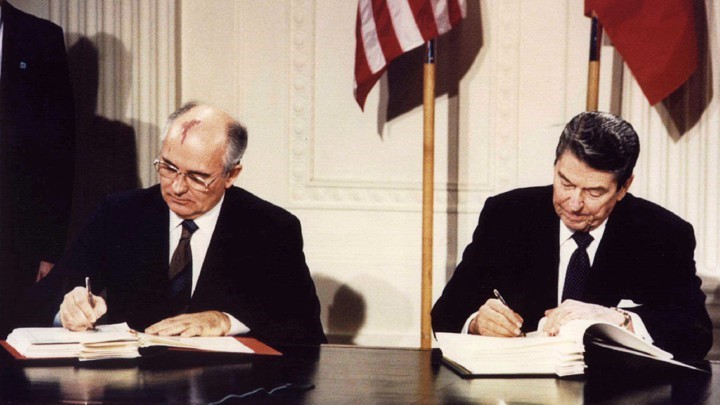

The President’s intention to withdraw from the 1986 Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty, the only arms control agreement to outlaw an entire class of missiles, is very worrying and, to be sure, a highly regressive step. But again, this is (unfortunately) not entirely without precedent. George W. Bush withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2001 – an agreement that outlawed National Missile Defense, perhaps the most potentially destabilising system that any nuclear power could develop (on the grounds that it would nullify every other missile programme in the world and thus permit offensive action without fear of symmetrical retaliation). Moreover, the United States has often failed to live up to the spirit and the letter of the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), generally implementing it in a selective way, such as through its support for the Indian civilian nuclear power programme – assistance that the NPT permits only to states that forgo nuclear weapons. Trump’s INF policy is bad – but it does not make him an outlier.

The US withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, signed by the Obama administration with Iran (as well as the EU, Germany, China, and Russia), is another regressive and dangerous step. But sadly, it was Obama’s effort to negotiate with Tehran that departed from the recent historical norm, not Trump’s rejection of that diplomacy. The Clinton administration’s 1995 trade embargo against Iran; its extraterritorial sanctions targeting countries that traded with Iran (and Libya); its designation of Iran as a “rogue state”; and the country’s subsequent inclusion in the Bush administration’s “axis of evil” – all of these measures were in keeping with the now-forty-year-old campaign to isolate and contain Iran. Obama’s agreement with Tehran was hugely unpopular with Republicans and even some Democrats. Trump’s position reflects mainstream Republican opinion and is in keeping with Washington’s longstanding refusal to recognise the Islamic regime in Tehran.

At the NATO leaders summit in Brussels in July 2018, Trump unleashed a broadside against Germany, which he claimed was “a captive of Russia” because of its reliance on gas imports from Moscow. Yet he signed onto the leaders’ summit agreement, which pledged to establish a new NATO Readiness Force capable of deploying thirty naval units, thirty ground units, and thirty air squadrons in thirty days – the ‘30 x 30 x 30’ plan – aimed largely at Russia. While the leaders claimed to prefer constructive co-operation with Moscow, they concluded that “there can be no return to ‘business as usual’ until there is a clear, constructive change in Russia’s actions that demonstrates compliance with international law and its international obligations and responsibilities.” Trump’s rhetorical prevaricating over his commitment to NATO did not seem to impact upon the final agreement of the summit.

Finally, the administration has also continued the Obama era bombing campaign in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Yemen. Echoing its two predecessors, it invoked the September 2001 Congressional Authorization for the Use of Force, passed after 9/11, as its legal justification, as well as the Obama administration’s extension of the AUMF to al Qaeda “and Associated Forces” – thus permitting action against groups that did not exist when 9/11 occurred.

Given Trump’s dire lack of policy knowledge, his penchant for frequently replacing cabinet members, and his erratic temperament, this picture may well change. In his first two years, however, Trump’s foreign policy has been characterised more by continuity than change.