By Professor Kevern Verney, Associate Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Edge Hill University

Media images of Trump rallies for Republican candidates in the midterm congressional elections are commonplace. Addressing his political base, the President has highlighted policy pledges made during the 2016 election. Pledges he has fulfilled in office. The message is clear. In contrast to previous administrations, ‘promises made’ have been ‘promises kept’. That is the unique character of his presidency. There is some justification for such claims. The Affordable Care Act, or ‘Obamacare’ as it is known, may not have been repealed. Still less replaced by a cheaper, more efficient, form of health insurance, or ‘Trumpcare’. But in other ways Trump has delivered. He has appointed two socially conservative justices to the United States Supreme Court. There have been sweeping tax cuts. The economic recovery, began under the Obama administration, has been maintained. Unemployment is at a 49-year low. A new free trade deal has been negotiated with Canada and Mexico. Islamic State has been driven from its powerbases in Iraq and Syria.

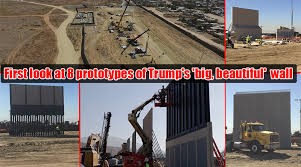

But, arguably, Trump’s best-known 2016 campaign commitment was to ‘build a great, great wall’ along America’s southern border. He also pledged to make ‘Mexico pay for that wall’. These promises remain unkept. The question is why? After all, the Republicans have enjoyed majorities in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. Addressing a joint session of Congress, in February 2017, Trump said construction of the wall would begin ‘ahead of schedule’.

Thus far there has been little progress. Congress has approved funding for the repair and maintenance of existing stretches of wall, but they were built during the second George W. Bush administration. Work on the Trump wall has been limited to the construction of desert prototypes.

My essay for Mara Oliva and Mark Shanahan, eds., The Trump Presidency: From Campaign Trail to World Stage, examines the viability of a border wall. It highlights the formidable financial, legal, logistical and political problems that would have to be overcome. If anything, those challenges are now even more daunting.

Most electoral forecasts suggest the Democrats will gain control of the U.S. House of Representatives in the midterm elections. They could be wrong. Trump’s victory in 2016 defied the predictions of most pollsters. But even if Republicans retain control of the House it will be with less seats. The current Republican House majority of 236-193 could be reduced to single figures. And that’s by the most optimistic forecasts. The more than $1 trillion annual budget deficit incurred by Trump’s other spending commitments is another problem. Tax cuts and big increases in military expenditure come at a price. Politicians from either party will be reluctant to authorize the additional $25 billion, or more, needed to build the wall.

South of the border there will be a change of government. In July 2018, Socialist candidate Andre Manuel Lopez Obrador was elected as Mexican President. He campaigned on promises to ‘make Trump see reason’ and ‘put him in his place’. Since then relations between the two men have been more cordial. But it is a safe bet that he doesn’t share Trump’s view that Mexico should pay for a wall. Obrador will take office in December.

Unable to make progress on the wall Trump has shown his tough anti-immigration credentials in other ways. In May 2018 his administration introduced a controversial new immigration policy. Undocumented adult immigrants from Mexico were arrested and criminally charged. Parents were separated from their children. Shocking images of traumatized children caged in government detention centres prompted widespread outrage. Both within the United States and internationally. The Trump administration abandoned the family separation policy the following month.

More recently, Trump has threatened to cut off U.S. aid to Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador. The move is an act of retaliation. Trump blames the governments of those countries for failing to stop a caravan of migrants. The caravan is now journeying through Mexico to seek entry into the United States. Coinciding with the midterm elections, Trump has made much of the issue. He has cited dubious reports that the migrants were funded by George Soros, a billionaire liberal philanthropist. He has claimed that the exodus was encouraged by Democrat politicians.

Trump clearly hopes this will influence the outcome of the elections. But such manoeuvring may have another motive. To deflect blame. If the wall is still not built in 2020 it will not be Trump’s fault. It will be the fault of a Democrat controlled House of Representatives.

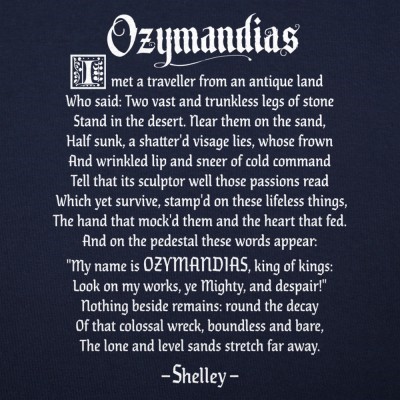

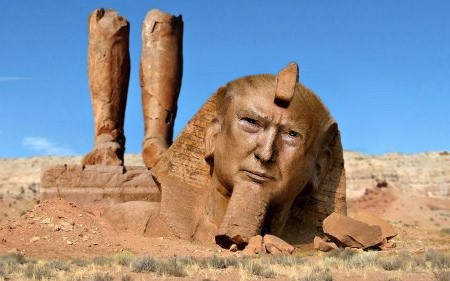

Trump’s scapegoating of others for his own shortcomings follows a familiar pattern. It reflects the President’s past business dealings, as Republican party strategist Rick Wilson has observed. ‘It was classic Trump pitchmanship; promise an impossible project, get someone else to pay for it, and leave investors holding the bag when it never gets built’. Meanwhile, there is still no wall. The desert prototypes could end up being the only tangible realization of the President’s campaign promise. If so, they may become like the broken monument in Shelley’s poem Ozymandias. A poignant reminder of a grandiose vision and the fleeting nature of political power.