by Professor Iwan Morgan, Professor of United States History, University College London

In my chapter for Mara Oliva and Mark Shanahan, eds., The Trump Presidency: From Campaign Trail to World Stage, I compare Ronald Reagan and Donald Trump’s first year as president. One of the issues I discussed was the difference between Reagan and Trump’s early approach to Supreme Court nominations. Given the recent controversy over Brett Kavanaugh’s Senate confirmation, it is interesting to move the Reagan-Trump judicial comparison on from their first year as presidents. I discuss here the controversy surrounding Reagan’s nomination of Robert Bork in 1987 and what the episode portended for present day Supreme Court nomination politics.

Firstly, however, it is worth exploring Reagan’s nomination of the first woman to sit on the Supreme Court. Less than a month before Election Day in 1980, polls showed Jimmy Carter drawing level with Reagan for the first time since the start of the campaign. Reagan’s pollsters warned him that he needed to shore up support from women voters who worried about his belligerent rhetoric on Cold War matters. On October 14, Reagan announced at a press conference that he would name a woman to ‘one of the first Supreme Court vacancies in my administration.’ Within weeks of him entering office, Associate Justice Potter Stewart announced he would retire at the end of the current Supreme Court session. Despite the reservations of Attorney General William French Smith, who wanted a reliable conservative jurist, Reagan insisted on honouring his campaign pledge with the immediate nomination of a woman. From a list of four names, Reagan interviewed Sandra Day O’Connor, who came with endorsements from two of his key campaign supporters, Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona and Senator Paul Laxalt of Nevada.

Such was the good impression O’Connor made on Reagan, he decided to put her name forward without interviewing anyone else. The only real opposition to her nomination came from the Moral Majority and the New Right, who objected to her support of the Equal Rights Amendment and refusal to limit abortion rights as an Arizona state senator and then appeals court judge. Rapidly confirmed by 99 votes to nil by the Senate on 21 September, she became one of the swing votes on the Supreme Court until her retirement in 2006 – supporting its liberal bloc in cases involving state government restriction of abortion rights and gay rights and voting with the conservative bloc on affirmative-action judgements.

Donald Trump’s 2016 campaign promise was to appoint a conservative to the Supreme Court vacancy created by the death of Antonin Scalia, a seat kept open by the refusal of the Republican-controlled Senate to consider President Barack Obama’s nomination of Circuit Judge Merrick Garland to fill it. Trump’s choice was Neil Gorsuch, who carried the endorsement of the libertarian Federalist Society as a reliable judicial supporter of original intent constitutional interpretation. He also received the top rating of ‘well qualified’ from the American Bar Association, the voice of the legal profession. Nevertheless, an allegation of plagiarism pertaining to a book he had written on euthanasia gave Democrats cause to question his integrity. Accordingly, the Senate voted on party lines to approve his confirmation by 54 votes to 45 on 7 April 2017. As anticipated, Gorsuch has consistently sided with the Supreme Court’s conservative bloc, but his appointment did not change the balance-of-power on the Court because he was a like-for-like replacement for the highly conservative Scalia.

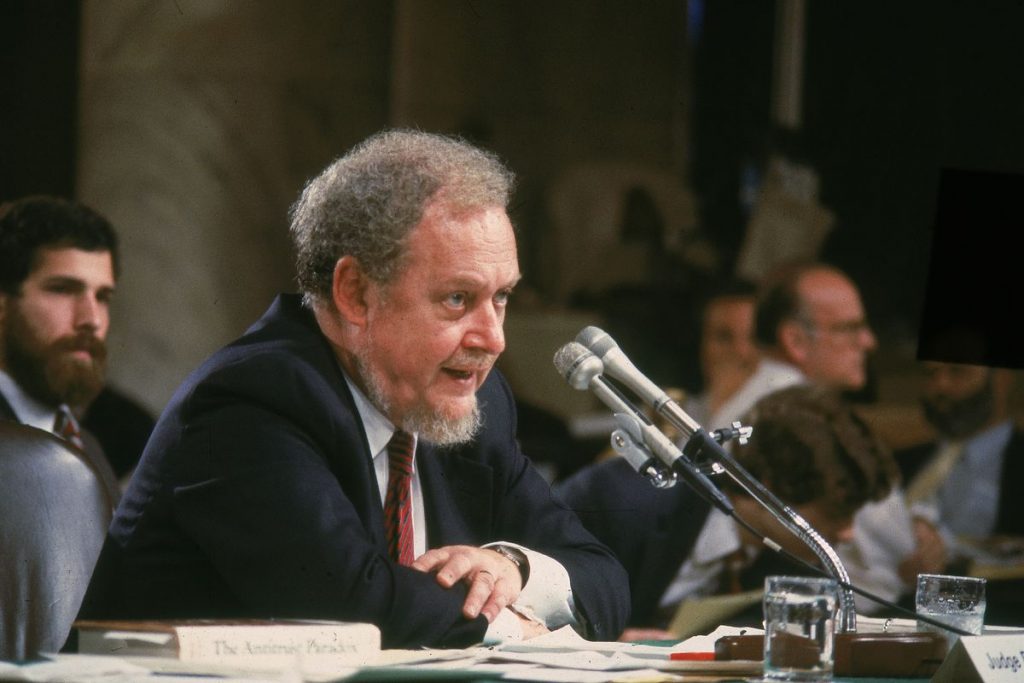

The Gorsuch confirmation imbroglio confirmed the recent trend to assess Supreme Court nominees on political considerations rather than their legal expertise. Arguably it was the Senate’s rejection of Reagan nominee Robert Bork that set this in motion some thirty years ago. Bork had been on the Justice Department’s radar as a highly qualified and brilliant conservative jurist since day 1 of Reagan’s presidency, but he came with the considerable baggage of his provocative writings as a legal scholar over a quarter-century and his decisions as a US Court of Appeals judge for the District of Columbia since 1982. Civil rights groups considered him an enemy of affirmative action, women’s groups thought him opposed to abortion right, and civil liberty organizations were also hostile to his stand pertaining to First Amendment rights.

When Nixon appointee and swing-voter Lewis Powell announced his retirement from the Supreme Court, Reagan justified Bork’s nomination to replace him as a recognition of his formidable legal mind. However, Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts framed the Senate’s consideration of the nominee with his statement of opposition;

‘Robert Bork’s America is a land in which women would be forced into back alley abortions, blacks would sit at segregated lunch counters, rogue police could break down citizens’ doors in the midnight raids, schoolchildren could not be taught about evolution, writers and artists could be censored at the whim of government, and the doors of the federal courts would be shut on the fingers of millions of citizens for whom the judiciary is – is often the only – protector of the individual rights that are at the heart of democracy.’

As Washington Post White House correspondent and Reagan biographer Lou Cannon noted, this set off a lobbying campaign by various organizations that used the kind of symbolism and simplicity against Bork that Reagan himself had long employed to promote his conservative agenda. Perhaps this was a justifiable case of tit-for-tat, but it also opened the Pandora’s box of subordinating Supreme Court appointments to politics.

Whatever Bork’s conservatism, it was grounded in careful jurisprudence. He was not the enemy of Brown v. Topeka as some critics claimed, but he had significant reservations about Roe v. Wade as an ‘unjustifiable usurpation of state legislative authority.’ Bork did his own cause no good in his five days of Senate testimony in which he conducted himself with dignity but came across as aloof and distant, particularly to the television audience (polls showed public opinion turning against him afterwards). Reagan himself was missing in action at the critical time on a 21-day vacation at his California ranch, arriving back too late to lobby individual senators for support. On October 23, the vote would go 58-42 against Bork in the now Democrat-controlled upper chamber.

Perhaps the line from Bork to Kavanaugh is not a wholly straight one. Bork did not face personal allegations about his past. Reagan did not whip up base support for his nominee in the manner of Trump’s gross and disgraceful comments about Professor Blasey Ford at a rally in Mississippi in advance of the Senate vote on Kavanaugh’s confirmation. That said, the current subordination of the Supreme Court nominations to partisan politics dates to the Bork confirmation.

Very rarely in the past had political considerations resulted in the rejection of a Supreme Court nominee – the refusal to confirm Herbert Hoover’s nominee, John J. Parker, was the most recent occasion in 1929. True, politics had a hand in the Democratic-controlled Senate’s rejection of two Richard Nixon nominees in 1969, but each had other liabilities to justify this course of action. After Bork, however, almost every presidential nominee to the Supreme Court has become the subject of partisan scrutiny regardless of the quality of their jurisprudence.

There is also a further connection between the Bork and Kavanaugh nomination processes. With Bork’s rejection by the Senate, the Reagan White House put forward Douglas Ginsburg but media revelations of his pot smoking as an undergraduate and then as a young Harvard academic led to his withdrawal. It was third time lucky for Reagan – Anthony Kennedy, his next pick, sailed through his confirmation hearings, during which he expressed disagreement with the more extreme claims of original intent doctrine. For the next 30 years, Kennedy was a swing voter, and has effectively held the balance on the Roberts Court in recent years, sometimes voting with the liberal bloc and sometimes with the conservative one. It was his announcement of retirement that opened the way for Trump’s nomination of Kavanaugh.

Kavanaugh’s successful confirmation means that an avowedly conservative jurist replaces a swing justice. It therefore shifts the balance of power on the Supreme Court to the right. If Trump wins a second term, he may well be able make further nominations should octogenarians Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsberg, liberal justices appointed by Bill Clinton, decide to retire. In that event he would complete the ideological transformation of the Supreme Court, a goal that conservatives have been seeking since the Reagan presidency. Should the Democrats recapture the Senate in 2018 or 2020, however, they will do all they can to defeat his nominations.

So, ‘supreme controversy’ and the resultant politicization of judicial nominations are not going away any time soon.