by Dr Mara Oliva, lecturer in modern American history, University of Reading

In the final chapter of the Trump Presidency: from Campaign Trail to World Stage, I looked at Sino-American relations and argued that despite the aggressive rhetoric, the new Trump administration lacked a clear China policy. This will not only lead to a failure to implement campaign promises but more importantly, it will also create a power vacuum in the Pacific region that Beijing will be quick to fill, thus leaving US long-term allies confused. One year on, has the president finally identified US objectives in Asia?

To start with, the rhetoric has not toned down. If anything, it is more aggressive than during the campaign. Although Trump has been broadcasting his personal friendship with Chinese president, Xi Jinping, to all corners of the world, he has also repeatedly accused China of putting the US economy at a disadvantage, manipulating currency, being an intellectual property theft and cyber terrorist, and more recently interfering in the US mid-term elections. Vice-President Mike Pence’s October 4 speech at the Hudson Institute pretty much summed up the administration’s public stance. Though the target audience was the American people, comparing China to Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan did not go down well in Beijing. The VP was right in drawing attention to China’s unfair trade practices, its aggressiveness in the South China sea, and its disrespect for human rights, but the speech was not seeking to lower tensions. It was a strong re-affirmation of US unwillingness to negotiate, reflected in the so-called “trade war” initiated in early 2018.

In its second year, the administration seems to have made good on its campaign promise to hold China accountable for its unfair trade practices that damage US economy and industry. Accordingly, Trump imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels and washing machines and then quickly escalated them to covering $250 billion of US imports from China. Beijing retaliated by imposing tariffs on the bulk of US imports. This tactic best exemplifies how the administration’s lack of a grand strategy in Asia can lead to damaging long-term consequences for all parties. While Trump has skilfully turned these tariffs into a propaganda manifesto to promote his ‘America First’ agenda, they are not an effective solution to contain a rising China or restart the declining US manufacturing industry.

On the contrary, in the long run the tariffs will prove to be costly and will not push the Chinese into negotiating. They will, instead, harden their positions. They will make American products less competitive and, ultimately, consumers will have to cover the extra costs. It would be better to step back and re-engage in meaningful dialogue. Something voters in the Rust Belt have already figured out. In 2016, Trump won the presidency with victories in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin, mainly because industrial decline had left working class voters angry. Last Tuesday, Democrats in these three states swept the races for Senate and Governor, and picked up valuable House seats. Perhaps, that’s why Trump and Xi have agreed to meet next month at the G-20 summit in Buenos Aires.

The president’s erratic approach to foreign policy is clear in dealing with North Korea too. In 2017, he threatened nuclear war. One year later he declared that he and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un had fallen in love. Not surprisingly, he was quick in taking credit for what, on the surface, looks like a breakthrough in stabilizing the Korean peninsula. In reality, much credit should go to the South Korean leader, Moon Jae-in, who did most of the groundwork to make the Singapore summit possible. Singapore was a great diplomatic victory for Kim. It consolidated the legitimacy of his regime. Whereas Trump looked unprepared and weak. Negotiations have now reached a deadlock. The US’s one remaining ace is the possibility of formally ending the state of war between the two Koreas. The Korean War ended with an armistice in 1953, not a peace treaty; both North and South Korea want to put one in place this year. North Korea has made a peace declaration an essential precondition for denuclearisation, while South Korea hopes that the mere prospect of a peace treaty will make Kim more amenable to abolishing his nuclear programme for good. Trump, like all previous US presidents, wants denuclearisation.

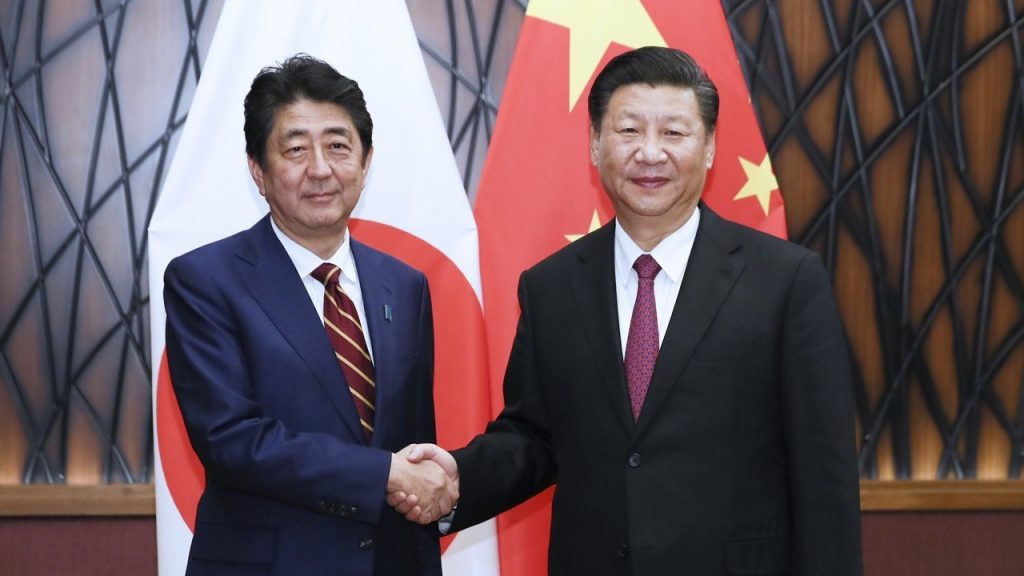

This administration’s China policy has made America’s position in Asia more unsettled than any point in recent history. It has also pushed historical US allies, such as Japan, closer to China. Last week, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe travelled to Beijing to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the China-Japan Treaty of Peace and Friendship. It was the first time a Japanese leader visited China in seven years. The two countries share a concern over Trump’s unpredictable actions. The US has imposed tariffs on Japanese exports too. The administration’s withdrawal from major international agreements, such as the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), the Paris Climate Accords and the Iran Nuclear agreement, its handling of the North Korean threat, and its overall isolationist approach to foreign policy, have turned Washington into an unreliable partner. Though Sino-Japanese relations are bound to be influenced by old grudges, the two understand that a coordinated economic approach is in everybody’s interest. Indeed, Tokyo and Beijing are currently collaborating on the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), a multilateral arrangement that would encompass all of Asia’s major trading partners and exclude the US.

Trump has disguised his lack of understanding and knowledge of diplomacy under the slogan of ‘America First.’ Foreign policy is simply another domestic propaganda tool to consolidate support from his conservative base. His rejection of expert advice might give the impression to voters that he is keeping his promise of ‘draining the swamp’ but, in reality, it undermines strategic thinking about the US role in the world and its long-term goals in specific regions. The confused China policy is one of many examples. My chapter in the edited collection is entitled Much Ado About Nothing. The assumption behind this was that despite Trump’s crazy campaign threats to bring trade cases against China, among others, the international order constraints would eventually force him to follow his predecessors’ policies. Although in his second year in the White House, he has broken away from traditional approaches and taken some bold initiatives, these have weakened American position in the Pacific region and have created a leadership vacuum that China has quickly filled. US objectives in Asia are still not clear. Trump’s transactional approach to the area resembles more a Comedy of Errors and reinforces the general perception that he was unprepared for the job.