Blog post from The History of Parliament by Dr Jacqui Turner from the University of Reading and PhD student, Kate Meanwell, discussing Nancy Astor’s role as a mother to her five children as well as a representative of mothers and women as the first female MP to be elected to the House of Commons in 1919:

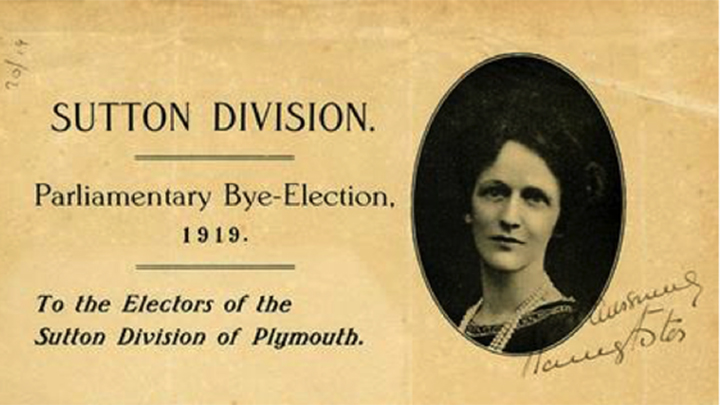

Nancy Astor was not just the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons, she was the first wife and the first mother. Throughout her 1919 by-election campaign, the images painted of Nancy Astor were of ‘A fighting woman’ for Plymouth Sutton; ‘A voice for women and children’; ‘A champion of the disadvantaged’; ‘A woman, wife and mother’ and in turns a ‘proxy’ for her husband. Astor’s image was constructed and deployed as deemed necessary though the issue that caused the greatest debate was that of Astor as a working mother.

Viscountess Astor won the by election in 1919 and became the first female voice heard in the chamber of House of Commons. She was elected to Plymouth Sutton in with more votes than the Labour and Liberal candidates combined, replacing her husband as the sitting Conservative and Unionist MP after he ascended to the House of Lords on the death of his father. Nancy’s time in the seat was initially intended to be temporary as Waldorf worked to extricate himself from the Lords and return to his seat in the Commons or negotiate a means of sitting in both. He could not.

In addition to her position as a role model and voice for women, what seemed to make Nancy the “right woman” in many minds was her ability to embody ordinary ‘feminine virtues’ associated with mothers and caregivers. In addition to being the first woman in the House, Nancy was the first mother to take her seat – she entered Parliament when her youngest child was under two years old.

It may have been a useful device in the campaign to present Nancy as in some way ‘tried and tested’, lending her a sense of familiarity and credibility, but her position and standing was nevertheless unique and indeed historic. Many correspondents sum up the multi-faceted nature of Nancy’s appeal as a woman as “a threefold representative: as woman, wife, mother…”(MS 1416/1/1/1721 – Letter from staff at The Observer, dated 29 Nov 1919). Undermining the idea that Nancy ever could have provided a seamless link with what had gone before. It may have been a case of “Astor once again” but it seemed likely that the similarities were confined to their shared name and Plymouth Sutton constituency.

This met with approbation amongst some of those who wrote to congratulate Nancy on her election – clearly, she was joining the ranks alongside many other parents. Nevertheless, in view of their wealth and privilege it may be that in this respect Nancy had more in common with the fathers she was joining than some of the mothers she was representing; one correspondent commented that “it will be a good thing to have in Parliament one who knows by experience as a mother…the responsibilities of the family”, although her day-to-day responsibilities in terms of her family were very different from the average voter (MS 1416/1/1/1723, Letter from B N Swinson, 29 November 1919).

There were dissenting voices who expressed concern at Nancy’s maternal status. Nancy’s opening speech at the meeting of the Party Association stated:

I have heard it said that a woman who has got children shouldn’t go into the House of Commons. She ought to be home looking after her children. This is true, but I feel someone ought to be looking after the more unfortunate children. My children are among the fortunate ones, and it is that that steels me to go to the House of Commons to fight the fight, not only of the men but of the women and children of England.

While for the most part the press did not make a feature of Nancy’s status as a mother; it is interesting to note when it did, she was consistently presented in a positive light and was feted as an “expert on matters pertaining to motherhood and womanhood”, suggesting it was a pioneering asset to her candidacy and appealing to Nancy’s own ‘difference feminism’ (MS 146/1/1/31 – Press cuttings 1919, Liverpool Courier, 8 November 1919). Inevitably, photographs were circulated of Nancy with her husband and children, The Sunday Pictorial of 9 November 1919 ran a photograph of Nancy with all six of her children, captioned ““OUR NANCY” AND HER BEST SUPPORTERS”.

Nancy’s maternal status was a previously unarticulated benefit for any MP and was a legitimate and logical extension of her position as a mother. However, the significance of Nancy’s maternal status should not be overstated –the idea of Nancy as a mother was dwarfed by the overwhelming and all-encompassing difference of Nancy being the first woman MP.

Nevertheless, Nancy was taken at her word and viewed as a special representative for vulnerable and disadvantaged members of society, in much the same way as she was regarded by many as a special representative for women. The Observer told Nancy “we are convinced that all your actions in the House of Commons will be on the side of those least able to speak or act for themselves.” (MS 1416/1/1/1721 – Letter from staff at The Observer, 29 Nov 1919)

An ambitious agenda lay before her.

JT/KM