by Dr Steph Adler, CBCP Early Career Visiting Fellow

New boxes come across the sea

From Mr.Mudie’s libraree [sic]

(W.S Gilbert, Babs Ballads 1868)

In May 2022 I was delighted to embark on an early career visiting fellowship at the University of Reading’s CBCP. The fellowship afforded me the opportunity to build a picture of the international nineteenth /early twentieth-century publishing scene as part of my potential postdoctoral project examining the global impact of Mudie’s library, 1842-1937. Despite the significance of Mudie’s to the English literary marketplace, there has been no full-length study of its influence abroad. My project hopes to address this gap and examines the complexity of ways that Mudie’s ‘select’ branding inadvertently reinforced and resisted English middle-class values through the process of exporting his subscription model while facilitating it to be repurposed and revalued for different audiences.

Firstly, some context. According to James Milne, writing in the Graphic in 1919, ‘when a batch of “Mudie [book] boxes” were wrecked with a ship, they were full of novels. So well made were those boxes that the novels came out of them smiling and unhurt.’ While the image of books by Gaskell, Eliot and Hardy, amongst many others, languishing at the bottom of the ocean is arresting enough in itself, it points to an even more intriguing story.

The idea for the project came out of my doctoral research that rethinks Mudie’s ostensibly censorious influence on the novel as inadvertently producing literary innovation rather than repressing it. Through an article by William Preston in Good Words in 1894, I discovered that from approximately 1844, Mudie was exporting second-hand books to Germany, Austria and Russia. Likewise, ‘…schools of art in Australia, the literary institutes of New Zealand, the Mechanics’ Institutes of Polynesia… all received large consignments of books from Mudie’s…’ Preston also discovered 15,000 volumes from Mudie’s in the Kimberley Public library of South Africa.

The project aims to investigate the extent to which Mudie’s impacted networks of libraries and their readers on a global scale. These libraries held a unique position in that they required subscription fees from their English clientele while simultaneously enabling their excess stock to be consumed free of charge abroad. While conventional scholarship positions the colonial library as perpetuating imperial discourse, I hope to explore how the global dissemination of Mudie’s books could be seen to have also democratised reading, facilitating access to texts (for example, by Ouida and Hardy) that called into question dominant Victorian ideas such as imperialism. On the one hand, the library furthered an imperialist agenda by distributing fiction to readers in the colonies. On the other, its ‘select’ nature was undermined by the act of transporting books from the private realm of the English subscription library to public and military libraries and mechanics institutes across the world.

For example, the Borroloola Library of Australia was founded through donations of Mudie’s books and welcomed indigenous readers. Described by Nicholas Jose as ‘…a wild little outpost in tropical Australia,’ Borroloola is a township in the northern territory, near the Gulf of Carpentaria and 970 km from Darwin. The library was founded in 1891and presided over by local policeman Corporal Cornelius Power who organised the purchase of around 3000 books, most of which came from Mudie’s Select Library. Apparently, the collection was stored ‘in a narrow cell at the back of the old iron courthouse’ where they were subject to the ravages of white ants, silverfish and the tempestuous weather. The courthouse where the library was housed was damaged by a cyclone in 1937 which meant the library closed by the end of the second World War and all its remaining books were sent to Darwin. Although the surviving books are difficult to track down, archival records of library catalogues give a tantalising glimpse into its diverse circulation. These included novels by Hardy, Kipling, Stevenson, Dickens, Conrad, Schreiner, Austen, Zola and plays by Strindberg and Wilde. It is important to note here, that these authors represent a spectrum of attitudes to empire from Kipling who could be accused of jingoism to Hardy who, in 1918, declared, as Angelique Richardson notes, ‘“better let Western ‘civilization’ perish”. He placed “civilization” in inverted commas.

If we think about this library in the context of what we know about Mudie’s select cliente, new perspectives on transnational connections can be revealed as the ‘select’ library books that were consumed by the metropolitan middle-class to whom Mudie catered, become repurposed and revalued for a different audience with different needs. Rather than positioning Mudie’s library then, purely within a national framework, we can rethink it as a more complex enterprise where the national and international combine in a symbiotic relationship. The Victorian Library was not simply a static symbol of Britishness but a transnational network that narrowed the gap between otherwise disparate communities and crossed boundaries of culture, ethnicity and class.

So that is the project in theory. In practice though, it is a little more complicated. One of my stumbling blocks has been finding material evidence of Mudie’s overseas subscribers. I have come up against several brick walls so far: for example, the Kimberley Library in South Africa that subscribed to Mudie’s no longer exists and my many attempts to contact its archive have been met with silence. Likewise, the author of the one book that has been written about Borroloola is proving to be enigmatic. However, I have found some rays of hope in the University of Reading’s special collections thanks to Danni Corfield’s discovery of a collection of Mudie catalogues spanning between 1881 and 1931.

Adorning the cover of the October 1896 catalogue is a Pegasus image symbolising Mudie’s as a globe trotting brand.

(UoR, Reading, MS 5799)

The catalogue includes an ‘Enlarged List of Cheap Editions’ dated Sept 1896 and a ‘Home and Colonial Library’ section. Significantly, in light of the affordable but not too cheap subscription rates for its middle-class readers, it offers reduced rates for public libraries on out-of-circulation books. Lists of second-hand reviews and magazines ‘can be forwarded, shortly after the publication of the Numbers ensuing, Postage Free, to all parts of Europe…’ And here, we have evidence to substantiate Preston’s claims of Mudie’s as a genuinely global brand: ‘Books for free libraries and public institutions… will be forwarded freight free to any port in the United States of America, Canada, China, India, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa’.

The catalogues also reveal the sheer entrepreneurship of the Mudie family with adverts for stationary, bookbinding, library furniture and even ‘Mudie’s Ocean Travel Department’.

Although the Mudie’s brand has become synonymous with Victorian middle-class small c conservatism, the library did not see or market it itself in that way. For example, note the caption to this picture of the library in the 1927-1928 catalogue:

‘A Corner of Mudie’s —The House that Supplies the World with Books’. Indeed, the description of the library as ‘progressive’ is born out with its offers of joint subscriptions with ‘special rates’ for ‘Reading Clubs, Welfare and Literary Institutions, Banks, Offices etc…’

(UoR, Reading, MS 5799)

While cynics could see this expansive enterprise as a way for the library to rid itself of cumbersome excess stock, by 1928, bulky three-volume novels were long gone and, while Mudie’s was certainly limping towards its inevitable demise in the wake of expanding public libraries, it was still doing its bit to democratise reading for the socially disadvantaged both at home and abroad. The question now is, who were those readers and how did the selection policies that underpinned Mudie’s books – regardless of their cost and accessibility – impact the lives of those who consumed them?

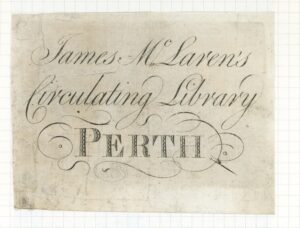

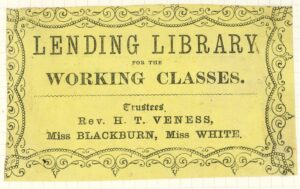

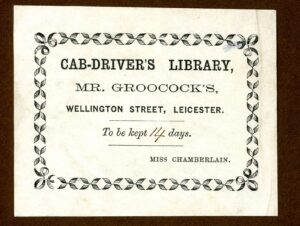

During my time at Reading, I also had the privilege of being shown around the Lettering, Printing and Graphic Design Collections in the Department of Typography & Graphic Communication. Tucked away in the farthest and perhaps leafiest reaches of the Whiteknights Campus, the collection includes a geographically diverse range of library book plates from Penzance to Kilmarnock and even as far afield as Perth. In addition to the well-known circulating library, it revealed those that catered for a more niche audience, for example, cab drivers’ libraries in Carlisle and Walsall. Likewise, there were plates for officer’s libraries, medical libraries, Mechanics Institutes and ‘a lending library for the working classes’.

(Amoret Tanner Bookplate Collection, Centre for Ephemera Studies, Lettering, Printing and Graphic Design Collections, Department of Typography & Graphic Communication)

While there are still many unanswered questions, both the collection of Mudie’s catalogues and the hidden gems in the typography department reveal the complexity of Victorian and Edwardian library consumption and the extent to which it transcended ostensibly fixed subscription models. Ultimately, then as now, the library shaped and grew, not simply according to the books it held but to the people who read them.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Nicola Wilson and the CBCP team for so generously supporting my research. Huge thanks also to Danni Corfield and Emma Minns for all their help in the archives.