This page introduces digital work by Reading colleagues on Samuel Beckett, whose archive is held in large part at the University, which is also home to a research centre and foundation devoted to Beckett studies.

The Beckett Digital Manuscript Project is one of the longest-standing digital resources in its field, and aims to reunite Beckett’s manuscript and typescript drafts from across 25 holding libraries, along with other material related to his writing process, in order to provide a comprehensive account of the development of each of his works. The project team has also contributed to the field of textual analysis by developing new tools to cope with specific challenges posed by the nature of Beckett’s corpus. In 2018, the project won the prestigious Modern Language Association (MLA) Prize for a Bibliography, Archive, or Digital Project, the highest award that can be given to a digital scholarly edition.

Staging Beckett was an AHRC-funded collaborative project (2012-15) between the Universities of Reading and Chester and the Victoria & Albert Museum, which examined the impact of productions of Beckett’s plays on cultural practices in the theatre across Britain and Ireland. The project produced a searchable database of productions, making use of Reading’s extensive Beckett archive. Although the project has concluded, new material, such as transcribed interviews and learning resources, continues to be added to the website.

- Samuel Beckett and the University of Reading

- The Beckett Digital Manuscript Archive: Towards best practice in genetic editing and criticism

– Technical Features - Staging Beckett: The Impact of Productions of Samuel Beckett’s Drama on Theatre Practices and Culture in the UK & Ireland

- The role of the repository

- Project teams

- Bibliography

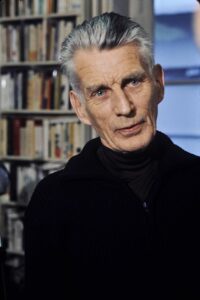

Samuel Beckett and the University of Reading

Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) was an Irish late-modernist playwright and novelist. He lived in Paris for most of his life and wrote in both English and French; he also usually translated his own works into the other language. Some of his most instantly recognisable titles are his plays Waiting for Godot and Endgame.

Samuel Beckett (1906-1989) was an Irish late-modernist playwright and novelist. He lived in Paris for most of his life and wrote in both English and French; he also usually translated his own works into the other language. Some of his most instantly recognisable titles are his plays Waiting for Godot and Endgame.

Beckett was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1969. A practitioner of surrealism and absurdism, he is the subject of consistent conversations about whether his work, which often has complex and ambiguous conclusions, has now become a marker of establishment theatre or retains its subversive origins.

Beckett was active from 1930 to 1988, producing a prolific body of work. His drafts and notes for most of his work has survived, creating the unusual opportunity to trace a writer’s development over a career of over half a century.

The University of Reading’s holdings of collections relating to Beckett are the largest in the world, and officially Designated by Arts Council England as an outstanding collection.

The collection took shape in 1971, when James Knowlson (Professor of French at the University, now Emeritus Professor), James Thompson (then University Librarian) and Jim Edwards (then University Archivist) organised an exhibition relating to Beckett. Since the University only had copies of 6 of Beckett’s published works, a mutual friend put Knowlson in touch with Beckett himself, who donated some of his manuscripts, which he later suggested that the University should keep. The opening of the exhibition, by playwright Harold Pinter, was only the start of the initiative. It was the start of a friendship between Knowlson and Beckett that lasted until the latter’s death – Knowlson wrote Beckett’s authorised biography – and also the start of the Beckett Archive.

Over time, the archive grew to become the Beckett International Foundation (est. 1988), a charitable trust which works with the University’s Special Collections department to care for the Beckett collections. The University is also home to the Samuel Beckett Research Centre, which hosts and promotes research activities relating to Beckett. Since 2017, it has hosted annual Creative Fellowships, enabling writers and other creative practitioners to derive inspiration from the unparalleled Beckett collections. The Foundation partnered with Trinity College Dublin to extend the scheme and the academic year 2022-23 saw the first Trinity Fellows.

(Image on the right – Harold Pinter opens the University’s Beckett exhibition in 1971. Behind him are James and Elizabeth Knowlson, and Librarian James Thompson)

The Beckett Digital Manuscript Project

Genetic editing is the account of a work’s genesis. It involves gathering and collating as many documents relating to the writing process as possible. These are further distinguished into ‘endogenesis’ (documents produced by the composition of the work, e.g. drafts) and ‘exogenesis’ (documents that contributed to the composition, such as the author’s copies of books quoted in the work). The editor then tries, as far as possible, to determine a chronological order to these documents: usually some will be part of an absolute chronology, because they are dated by the author, while others are inferred logically by the editor.

Why create genetic editions? As in other fields of literary studies, genetic editing examines narrative voice, perspective, and character, but lifts the lid to see how it’s made. Every writer has a blueprint which shapes how and where they get their ideas, and how they process them. This is of interest to a wide range of scholars, from creative writing students seeking examples of the craft, to historians who want to learn what events may have formed a work that went on to have significant cultural impact.

Genetic editions also expose the scholar to the physical and mental environment in which a writer worked, revealing aspects of which they go on to determine the significance. For example, Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn speaks in dialect, but in drafts of the work, his dialogue was written in normal English – the fact that this was a retrospective change may have bearing on a scholar’s assessment of the role of the character’s speech in his development. The poems of William Wordsworth are traditionally published in collections of his poetry alone, even though many of them were written in notebooks which he shared with his wife Dorothy, and he may have been writing with some of her work on the opposite page.

Samuel Beckett’s oeuvre presents distinctive opportunities and challenges for genetic editions:

- His publications span over 50 years, with an unusually high rate of survival of archival material.

- Relationships between his works are complex and non-linear, with linked motifs in multiple works, similarly to James Joyce’s fictional characters.

- Beckett wrote in English and French and self-translated his work into the other language (he did not consistently write in one first).

- 25 institutions hold manuscripts and other material relating to Beckett’s work, presenting legal and practical challenges.

The Beckett Digital Manuscript Project was born in the early 2000s, after an initial effort to produce physical variorum editions of Beckett’s bilingual works, in a series edited by Charles Krance: these proved unwieldy to use. It unites digitised images and encoded, searchable transcriptions of manuscripts from across all 25 holding libraries. A recent major update saw the addition of a catalogue of Beckett’s own library.

The immediately obvious benefit is that all the genetic material for a work is now in one place, and more accessible. But the digital editions’ features also allow intellectual engagement with Beckett’s work that would be far more difficult, if not impossible, to do by traditional means. The digital mark-up of the works allows scholars to make links across corpora that might otherwise have been missed. If Beckett underlined a sentence in a book he owned, and went on to use that sentence in a manuscript, it is possible to click through from one document to another, and to explore the materials that way. Since the resource focuses on one author, it is possible to delve deeper into the details than most.

Prior to these digital tools, it would be difficult to hold that amount of information in your brain, or indeed to remove the layers of structure relevant to your enquiry. The BDMP allows you to zoom in and out, both vertically and horizontally.

BDMP co-director Mark Nixon describes Beckett’s work as ‘like an art gallery in layering – most of it is down in the cellar’. In the BDMP, everything is on display. Beckett usually wrote on only the recto of his notebooks, leaving the verso for doodles: all the doodles are digitised, and you can search them by broad topic. The team has aimed to encode everything, explaining how they did so, and then leave the choice in the hands of the individual scholar. You might not be interested in which parts of a manuscript Beckett wrote in black or blue pen – but that information is there. It is up to you to determine what information is relevant to your own research question.

For some scholars, nothing replaces the experience of handling a manuscript: the poet and librarian Philip Larkin famously spoke of the ‘magical value’ of encountering ‘the words as [an author] wrote them, emerging for the first time in this particular miraculous combination’. He had particular incentive to insist on this, as he was giving a lecture on the need for British libraries to act together to acquire literary manuscripts to keep them in the UK. While the BDMP team acknowledge this deficit of a digital edition, they regard it as the only deficit, and point out that getting to have the miraculous experience in the first place is a privilege: now, a PhD student in Tokyo can look at Beckett’s manuscripts, instead of having to travel to 25 different libraries.

The BDMP is accessible on a subscription model, in accordance with the royalty agreement with Beckett’s estate, which owns the copyright. The project has a good relationship with the estate and the resource is good value within the sector, as well as being free to access from within any of the institutions that have contributed archival materials.

Nonetheless, the team have undertaken to be as open as possible in other ways: for example, the technology behind the project is fully documented, with any analysis tools the team has developed made available to others, the TEI/XML source file is available for each transcribed document, and the metadata submitted to ‘Modernist Networks’ (ModNets).

It is worth noting that although the BDMP has been going strong for 20 years, the team do not receive any payment for their work, and put any share of the subscription fees back into the upkeep of the resource. A close network of volunteers – many drawn from summer schools run by the project in Dublin – have also contributed to the bank of transcriptions. This situation emphasises the goodwill involved in digital projects, but also the fact that goodwill is a luxury commodity in which only scholars with permanent employment contracts can trade.

BDMP Technical Features

This section provides an overview of some of the features of the BDMP site. The technical functionality of the BDMP was provided by colleagues in the Centre for Manuscript Genetics at the University of Antwerp.

Overview

Each genetic edition of one of Beckett’s works is called a ‘module’.

The team works on modules together and the process is collaborative – colleagues can add comments or query a transcription.

So far there are 10 modules:

- Not I / Pas moi

- That Time / Cette fois

- Footfalls / Pas

- Fin de partie / Endgame

- En attendant Godot / Waiting for Godot

- Malone meurt / Malone Dies

- Molloy

- Krapp’s Last Tape / La Dernière Bande

- L’Innommable / The Unnamable

- Stirrings Still / Soubresauts

- Comment dire / What is the Word

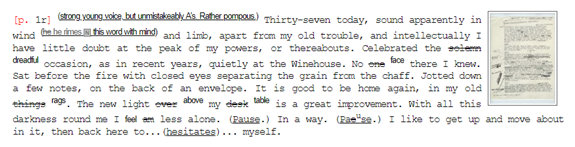

The screenshots in this section come from the edition of ‘Knapp’s Last Tape’, which is freely available as a demo.

TEI (Text Encoding Initiative) – The project uses TEI-XML, a form of XML (extensible markup language) for most of its search functionality. XML makes a document readable by a computer. The Text Encoding Initiative is a community that designed specific XML parameters suited to textual analysis.

At its most fundamental level, XML tells the computer how to display a document. This is particularly crucial for Beckett’s manuscripts, which contain high amounts of deletions and insertions. The markup can also split documents into sections, so that the transcription for one particular section can be displayed, and to identify units of the text for the collation engine.

From the user’s point of view, XML significantly increases search capabilities across a database. For example, if ‘Shakespeare’ was sometimes spelled ‘Shakspere’ in a document, a Ctrl+F search would not return those instances. But if a scholar marked up both ‘Shakespeare’ and ‘Shakspere’ as referring to a named entity, then a query on the data would yield all examples. As noted above, digital markup allows users to make connections across multiple works that might otherwise have been missed, because the query will return results from all works even if they were transcribed by different members of the team.

What is crucial to note here is that XML is a layer of interpretation. The BDMP has endeavoured to make this as transparent as possible, with full documentation of their editorial principles available on their site.

Extract from the transcript of a corrected typescript of ‘Knapp’s Last Tape’, and a section of the XML encoding, beginning, ‘The new light’, which contains deletions, insertions and crossing-out.

Handwritten Text Recognition – The team also used Beckett as a case study for advancements in machine-assisted transcription. 400 transcribed pages of Beckett’s notoriously difficult handwriting were used to train algorithms for Handwritten Text Recognition. In the course of this, the team found that the results were more accurate if separate algorithms were created for French and English.

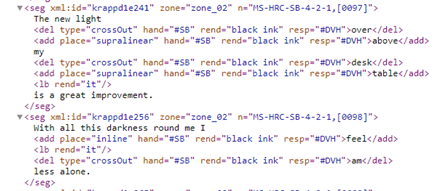

Collation – Collation is the process of comparing variations in manuscripts and is a key stage of creating an edition of any text. Collation can involve establishing what the author wrote (particularly in the case of ancient manuscripts), or examination of changes made from draft to print can illuminate the author’s intent behind a scene. Manual collation is a painstaking process, especially for works with many drafts.

In the BDMP, this is done with computational tools. Every single sentence is numbered, in every single version, from draft manuscripts up to printed proofs. Clicking on the numbers will lead to the composition history of that sentence.

A sample transcript of one of the notebooks that form part of the drafts of ‘Krapp’s Last Tape’, showing numbered sentences.

The website integrates CollateX, a tool developed for digital collation. The team took this one step further and developed HyperCollate, specifically designed for collation of texts that include revisions.

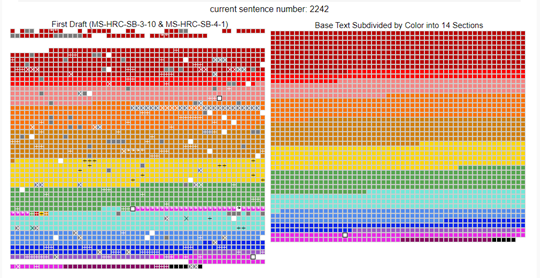

Visualisations – The website includes animations showing the composition of a text in the order it was written. Sentences are colour coded to show where each of them ended up in the final version.

Below is a visualisation of the writing sequence for L’Innomable (The Unnamable). The cursor is held over sentence 2242 (the first magenta box on the left-hand block): the corresponding position in the final version is whited out (in the right-hand block).

You can find more information on the development of these visualisations here.

Staging Beckett

Staging Beckett examines the impact of Beckett’s theatre as performances, on the theatre community including directors, designers, performers, companies and institutions. It also considers how particular productions were responding to their specific cultural, political and economic contexts. To aid in addressing these questions, the project created a database of all known productions of Beckett’s work, thus making a claim for performance history as an important aspect of knowledge, traditionally under-recorded because the live event itself cannot be captured.

Where BDMP is about genetics and Beckett’s creative process at the point of composition, Staging Beckett examines the collaborative creative process of putting together a production, with the various people, venues, and funders involved. It helps scholars to understand the ecosystem of theatre in different forms. This is not solely about the audience but reception more widely – not Beckett’s works as written, but as performed and seen.

The team’s archival research found ephemera relating to productions that were not known to scholarship. While the database does not capture the performance itself, it is a starting point for knowing there are questions there to be asked. There has occasionally been a perception that Beckett’s plays were primarily performed to London’s intellectual club theatre scene, but the database shows that they have consistently been performed widely across the UK. Waiting for Godot, for example, was performed in Halifax in 1958 as part of a touring production that was only known from a programme in the Victoria & Albert Museum. How did it relate to mainstream audiences? Was it niche? Theatre-goers who do not know much about Beckett are often surprised to find that Godot has considerable comedic elements as it comes from the music hall tradition, an important factor when considering how audiences received it. The database has created a legacy that enables scholars to look into this.

Another benefit of having the database is to make these data authoritative and show transparently where the information came from, and where users can go for more. In the Staging Beckett data schema, ‘Bibliographic, archive and web resources’ are recorded separately from ‘Record/data source’ – the latter refers only to the item used to confirm the details, whereas the ‘Resources’ section includes institutions that have holdings related to the production. This provides reliable data that are not available elsewhere. The BFI database, as well as the popular platform IMDB, contain cast and crew data for films but this information is not as easily accessible for theatre. The project uncovered production data about many non-canonical productions of Beckett, and had somewhere reliable to record it. As with any performing arts history, having the data aggregated means you can slice into it in different ways.

The role of the repository

The University of Reading’s Museums, Archives & Special Collections Services (UMASCS) has had a key role in the development of both Beckett projects. As well as being the custodians of the materials, staff have used the projects to increase both skills and equipment for digitisation. They have also brokered relationships with other holding libraries or record source providers, and advise on permissions and relationships with the Beckett Estate where applicable.

When the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project began, the team scanned everything themselves, and the role of archival staff was to provide the equipment, room, and materials. Over time this has evolved into much more of a partnership. A Museum of English Rural Life project secured some money for digitisation, leaving archival staff more scope to manage assets.

The BDMP was a conduit to getting the University’s Beckett materials scanned, which has had a knock-on effect on preservation. Traditionally, the Reading Room issues copies of Beckett manuscripts to reduce handling (in situations where the physical state of the original is not at issue). Prior to the BDMP, these were poor-quality photocopies, but now the BDMP’s high-resolution images can be used instead. Soon the Reading Room will have digital terminals especially for viewing them at the highest quality possible.

UMASCS managed the technical side of Staging Beckett, commissioning the database from Knowledge Integration and working with them to devise the data schema. The database uses Knowledge Integration’s CIIM, a piece of middleware, to aggregate data from various sources including theatre listings websites. The resulting website displays this information with filters to show only information relevant to Beckett.

The library or archive (of any institution) is often crucial to the sustainability and preservation of resources like this one, as it was for Staging Beckett – after the end of the project, the database was in danger of becoming unusable owing to a technology refresh. Staging Beckett was saved by the efforts of Guy Baxter (Head of Archives Services) in partnership with Knowledge Integration, who moved the database onto the newest iteration of the CIIM, which may now also be used as a starting point for other data-driven projects at Reading.

Both the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project and Staging Beckett highlight the potential of DH projects to continue to generate research investment for their institutions. The specific needs of the BDMP have led to new developments in the field of computational technical analysis; while the BDMP team are able to work on this on a long-term basis, other projects may be able to build cases for follow-on funding. As in the case of Staging Beckett, digital projects can be used as ‘proof of concept’ for new technologies and approaches, fronting the initial costs of new software or hardware at prices that fall through the cracks (too low for internal funding bids, but too high for centralised budget) and allowing professional services to experiment with how they will support future projects. Naturally, some projects are better suited to this sort of initiative than others – the key is to build a positive relationship with the repository for any collections-driven project. For both projects, this has proven essential to their longevity and continued scholarly impact.

Project team

Below follows short biographies of the team and contributors, to give an idea of the wide range of expertise that went into this research. Please feel free to contact them if you wish to know more about the projects, or to enquire about doing something similar.

Beckett Digital Manuscript Project

Mark Nixon (Co-Director) is Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of Reading, and Co-Director (with Anna McMullan) of the Beckett International Foundation. He has edited many of Beckett’s works, including his German diaries, and recently co-edited the volumes Beckett and Media (2023) and Samuel Beckett and Technology (2021).

Dirk Van Hulle (Co-Director) is Professor of Bibliography and Modern Book History at the University of Oxford, chair of the Oxford Centre for Textual Editing and Theory (OCTET) and director of the Centre for Manuscript Genetics at the University of Antwerp. His research focuses on literary writing processes and he has edited many volumes by and on Beckett, Joyce, and others. He is also the author of Textual Awareness (2004), Modern Manuscripts: The Extended Mind and Creative Undoing from Darwin to Beckett and Beyond (2014), and Genetic Criticism: Tracing Creativity in Literature (2022).

Vincent Neyt (University of Antwerp) is responsible for the design and implementation of the BDMP’s technical interface and code. Vincent is a doctoral researcher on the project ‘Creating Suspense Across Versions: Genetic Narratology and Stephen King’s IT’, working with Luc Herman and Dirk Van Hulle.

Other editors include:

- Wout Dillen, Senior Lecturer in Library & Information Studies, University of Borås, Sweden

- James Little, Marie Skłodowska-Curie Postdoctoral Fellow, University College Dublin

- Edouard Magessa O’Reilly, Professor in the Department of French and Spanish at Memorial University of Newfoundland, Canada

- Pim Verhulst, postdoctoral researcher, Centre for Manuscript Genetics at the University of Antwerp

- Shane Weller, Deputy Vice-Chancellor for Research & Innovation, University of Kent

Staging Beckett

Anna McMullan (PI) is Professor of Theatre at the University of Reading and Co-Director (with Mark Nixon) of the Beckett International Foundation. Her main area of research is the drama of Samuel Beckett, on which she has published two monographs (Theatre on Trial: The Later Drama of Samuel Beckett and Performing Embodiment in Samuel Beckett’s Drama), a co-edited volume (Reflections on Beckett), and many essays.

David Pattie (Co-I) is Professor of Drama at the University of Chester. He is the author of The Complete Critical Guide to Samuel Beckett (2001) and Modern British Drama: The 1950s (Bloomsbury Methuen Drama, 2012).

Graham Saunders (Co-I) is Professor of Theatre at the University of Birmingham. He is author of numerous monographs, most recently Harold Pinter (2023) and Elizabethan amd Jacobean reappropriation in Contemporary British Drama: ‘Upstart Crows’ (2017).

Trish McTighe is a Lecturer at Queen’s University, Belfast. She was a postdoctoral researcher on the Staging Beckett project and co-editor of the project’s two edited volumes. She has recently published Carnivals of Ruin: Beckett, Ireland, and the Festival Form (2023).

David Tucker teaches on the writing programme at the American College of Greece. He is the author of Samuel Beckett and Arnold Geulincx: Tracing ‘a literary fantasia’ (Continuum, 2012) and the short book A Dream and its Legacies: The Samuel Beckett Theatre Project, Oxford c.1967-1976 (Colin Smythe, 2013).

Matthew McFrederick is Lecturer in Theatre at the University of Reading. He was a PhD researcher on the Staging Beckett project, and in December 2016 he successfully defended his thesis on the production histories of Samuel Beckett’s drama in London. In 2015 he co-curated (with Professor Anna McMullan and Dr Mark Nixon) the exhibition Waiting for Godot at 60 for the Happy Days Enniskillen International Beckett Festival. He is also a theatre practitioner.

Lucy Jeffery is Assistant Professor in English at ADPoly, Abu Dhabi. She was a Teaching Fellow at the University of Reading and Postdoctoral Researcher for the Samuel Beckett Research Centre. She updated the design of the Staging Beckett website, wrote the learning materials, and edited the recorded interviews and talks for the project (made available as transcripts).

Guy Baxter (Associate Director of Archives Services, University of Reading) oversaw the development of the Staging Beckett database with partners Knowledge Integration and Obergine. Guy was PI of ‘Sustainable Infrastructure for the Digital Shift’, a project funded by AHRC under the Capability for Collections programme, and is currently overseeing the development of DH research infrastructure at the University of Reading.

The technical team also included Ramona Riedzewksi (Archivist & Conservation Manager in the Department of Theatre & Performance at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London) and Siobhan Wootton (Database Co-ordinator, University of Reading).

Bibliography

The Beckett Digital Manuscript Project. Access is free to University of Reading users logged in on campus.

[Article] Haentjens Dekker, R.; D. van Hulle; G. Middell; V. Neyt; J. van Zundert (2015), ‘Computer-supported collation of modern manuscripts: CollateX and the Beckett Digital Manuscript Project’, Digital Scholarship in the Humanities 30.3, 452–470.

[Article] Bleeker, E.; B. Buitendijk; R. Haentjens Dekker; V. Neyt; D. Van Hulle (2022), ‘Layers of Variation: a Computational Approach to Collating Texts with Revisions’, Digital Humanities Quarterly 16.1.

[Article] Sichani, A. (2017), ‘Literary drafts, genetic criticism and computational technology. The Beckett Digital Manuscript Project’, RIDE (A Review Journal for Digital Editions and Resources), Volume 5.

[Article] van Hulle, D. and M. Mixon (2007), ‘“HOLO AND UNHOLO”: The Beckett Digital Manuscript Project’, Samuel Beckett Today / Aujourd’hui 18, 313-22.

[Article] Doran, M. and G. Nugent-Folan (2021), ‘Digitized Beckett: Samuel Beckett’s Self-Translation Praxes Mediated through Digital Technology’, Anglia 139.1, 181-94.

The Staging Beckett project website.

[Book] Tucker, D. and T. McTighe (2016), Staging Beckett in Great Britain. Bloomsbury.

[Book] Tucker, D. and T. McTighe (2016), Staging Beckett in Ireland and Northern Ireland. Bloomsbury.

[Article] McMullan, A. and G. Saunders (2018), ‘Staging Beckett and Contemporary Theatre and Performance Cultures’, Contemporary Theatre Studies 28.1, 3-9.

[Article] McMullan, A.; T. McTighe; D. Pattie; D. Tucker (2014), ‘Staging Beckett: Constructing Histories of Performance’, Journal of Beckett Studies 23.1, 11-33.

~

Notes:

Text of this page by Olivia Thompson (Digital Humanities Officer 2021-23) based on discussions with the project teams and publications; views do not necessarily reflect those of the project teams.