by Dr Jacqui Turner, Department of History, University of Reading

This week was International Women’s Day and women were everywhere.

We were in the media, online, on TV, and crowded around both front benches in the House of Commons as, in the Budget, the Chancellor announced a further £5 million for projects to celebrate the centenary of the partial franchise in 1918, which first gave women a vote:

‘It is important that we not only celebrate next year’s Centenary but also that we educate young people about its significance. It was the decisive step in the political emancipation of women in this country and this money will go to projects to mark its significance and remind us all just how important it was.’ –Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond MP

Yes, it was, and yes, it is. My initial reaction, of course, is that this should be done in schools every year and beyond a few weeks on the GCSE History curriculum.

Maybe we do need that £5 million from Mr Hammond, which was allocated alongside £20 million to tackle domestic violence and abuse and £5 million for ‘returnships’ to support people returning to work after long breaks.

Maybe we do need that £5 million from Mr Hammond, which was allocated alongside £20 million to tackle domestic violence and abuse and £5 million for ‘returnships’ to support people returning to work after long breaks.

The positioning of women around the front benches on significant days or when key legislation is being announced is a long-standing tradition –very few ever find themselves there by seniority, some maybe, but they are often window dressing.

And why do they need to be there at all? Are we harking back to the days of our first female MP, Nancy Astor, who would ‘disrupt proceedings’ with claims that she knew best on issues relating to women because she was a woman? She may have done, but it is the very old feminist debate – equal rights versus inherent suitability based on gender difference (whilst acknowledging that the gender debate is much wider today).

The history of women in parliamentary politics is much broader than the centenary of the partial franchise, it also concerns those women sitting in the chamber of the House of Commons. I am a historian and as such I cannot help but look back, it is in my DNA and I research the work of female MPs in the 1920s. Who, you may ask? Exactly my point: can you name any?

I am also inclined to point out that the partial franchise in 1918 was not the only monumental piece of legislation relating to women and political power passed in 1918. While we joyously prepare to spend the Chancellor’s £5million to celebrate the centenary of the partial franchise, a very small, seemingly innocuous piece of legislation that is of equal importance also passed through Parliament that year.

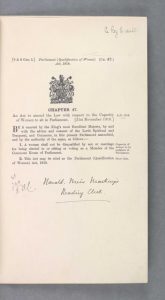

Sandwiched between two major pieces of legislation The Representation of the People Act 1918 and the Sex Disqualification Removal Act 1919 came 26 words that changed British democracy forever. The Parliament (Qualification of Women Act) 1918 enabled women over the age of 21 to stand for election to Parliament and changed our democracy forever. It simply stated that

Sandwiched between two major pieces of legislation The Representation of the People Act 1918 and the Sex Disqualification Removal Act 1919 came 26 words that changed British democracy forever. The Parliament (Qualification of Women Act) 1918 enabled women over the age of 21 to stand for election to Parliament and changed our democracy forever. It simply stated that

“A woman shall not be disqualified by sex or marriage for being elected to or sitting or voting as a Member of the House of Commons. “

That was it. No more and no less. It was ushered in quietly, three weeks later and arguably it was timed to avoid women reasonably organizing a campaign to stand in any great numbers at the 1918 General Election.

It was also something of a contradiction when taken alongside the Representation of the People Act – some women over the age of 30 and with property qualification gained the vote but any woman over 21 could stand for parliament and sit as an MP.

Jennie Lee MP, elected to Parliament at the age of 24 in 1929, sat in the chamber but still could not vote as the 1928 Equal Franchise Bill had not passed into law.

Jennie Lee MP, elected to Parliament at the age of 24 in 1929, sat in the chamber but still could not vote as the 1928 Equal Franchise Bill had not passed into law.

In her 1926 pamphlet ‘What the Vote has Done’, Millicent Fawcett (National Union of Societies for Equal Citizenship) championed the importance of the Parliamentary Qualification of Women Act amongst other legislation passed in the early 1920s.

Fawcett described the performance of women in elections as a result of the passing of the act that “renders it possible for a constituency to choose a woman as its representative in the House of Commons”. Few did and even fewer women succeeded when they stood. Despite Fawcett’s pride in the success of women in the successive general elections throughout the 1920s they were few in number. Fawcett argues that those women who failed to get elected “merely shared the fate of their respective Parties.” However, the continued presence of women in the House was a reminder of the wider female electorate and the need for progressive legislation.

And so back to the £5 million windfall for the centenary. Thank you very much Chancellor but the partial franchise was arguably not the only important piece of feminist legislation in 1918.

To find out more about the centenary, the continuing magnificent job done by the Vote100 project in Parliament can be found at

Link to more information on early female MPs from the Parliamentary Archives

Here at the University of Reading we are also looking forward to continuing the work on women in Parliament with the vote100 project but we are also looking forward to launching the centenary of Nancy Astor taking her seat in Parliament in 2019. Watch this space for more information relating to Astor100 coming soon.

More information about the Nancy Astor Papers in the University of Reading Special Collections