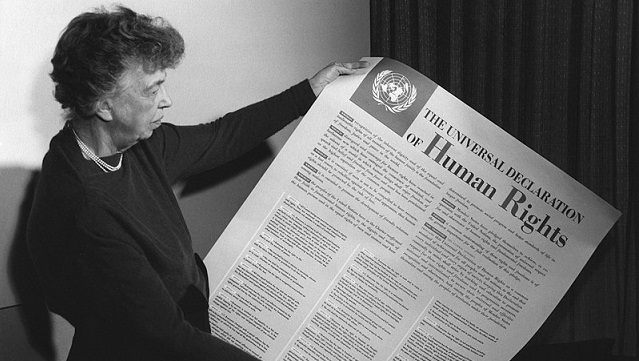

As stated by Professor Rosa Freedman, human rights belong to all people by virtue of them being human this is the first core principle of the UDHR. Yet more than 7 decades after the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the notion of having access to rights just because you are born is not a guarantee. In 2020, rights are politicised, criticised and not fully implemented into institutions, some of which I will discuss.

Accessibility of rights is left to the state to implement them (i.e. the government). This means that the government has to ensure our rights are protected. However, over the years this theory has not been easy to fulfil as we have found certain rights such as Article 3 ‘Right to Life’ or Article 15 ‘Freedom from Torture’ may be easier to fulfil as they require, the state to not harm humanity directly. But a right, such as everyone should have the ‘Right to Housing’ or the ‘Right to Education’ is harder for the government to achieve as these are economic social rights which require the government to intervene and create laws/ policies in order to achieve this right.

The COVID-19 Pandemic was a shock to the world and in no way was any country prepared for another pandemic to hit. But if predictions were to be made on countries that should have been able to recover and tackle the effects of a pandemic the UK would be considered. The UK is measured as being the 6th richest country in the world, has a free healthcare system, is advanced in technology, and in widely apart of the global north which means it is well established in its resources to provide for its citizens. Yet with all of its accolades, Britain is the first European country to hit 60,000 deaths in the UK. I believe one of the main contributing factors to their failure to protect the UK from COVID-19 is due to the deep inequalities and discrimination as well as lack of investment in prioritising health.

The ‘Right to Health’ can first be found in Article 25 of the UDHR, this is linked along with rights to ‘Standard of Living’ and other necessities. From the outside it seems as though the government has fulfilled their obligation in creating The National Healthcare Service. (NHS). A free healthcare system which allows all UK citizens to have access to health care. This same healthcare system, however, has suffered decades of, austerity cuts, which limits its ability to provide health for all and to gather resources. Therefore, in the event of a pandemic where it is a state’s obligation to priorities matter of public health and use the maximum of its available resources and the majority of the country is relying on this healthcare system, the NHS is already limited in its capacity. Which then, highlights the government’s failures in providing and ensure adequate healthcare.

But like all rights, the Right to Health is also dependant on it being actualised in a non-discriminatory manner. One of the core principles of human rights is that they are all interdependent and indivisible, which means that each right must operate equally and together. And a state must prioritise access for all and not some.

In the peaks of the first wave reports emerged that members of the Black, Asian and other Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities were up to 50% more likely to die of corona virus than their white counterparts.

There were many different factors and theories of why this was, but deep-rooted inequality is at the heart of this too. The NHS has had issues with its discrimination of certain groups in healthcare before COVID-19. For example, in 2018, an inquiry was made into why black mothers were x5 more likely to die in childbirth and the results of this study were discrimination in patient care. So even though we have a system that intends to provide free healthcare and adequate healthcare for all. Its intrinsic link to discrimination and bias to certain groups, makes the ascertainment of that Right to Health in effective for all.

In the height of a pandemic when providing PPE for NHS workers is a priority, it was found that the government could not provide resources for PPE quick enough when the pandemic first hit. The NHS staff made up of 13.8%, who have a non-British nationality, this means that not providing PPE is exposing certain groups to COVID-19 more than others. This leads to COVID-19 spreading disproportionality in certain communities as it is those of BAME background working the frontlines and are therefore over exposed to the virus. Therefore, actualisation of the right to basic healthcare and protection seems to be only available to those who are privileged in society to not be over-exposed to COVID-19. I use this as an example to build on the point that when the government ignores the unequal places individuals hold in society, then measures taken will always have an unequal effect.

It is in this ignorance that Matt Hancock: (Secretary of state for Health and Social Care) can boldly blame the continual spread of the corona virus on the Muslim community because they are ‘not abiding by social distancing’ rules. By creating a narrative that the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on minority groups is an individual fault, it perpetuates an idea of individual blame for deaths across the nation. It also renders the UK government blameless in its failure to slow down the spread of the virus. Furthermore, this public slander and Islamophobic rhetoric can have drastic effects on the Muslim community and public perception of certain groups. Claiming that a community is responsible it can desensitise empathy; if another report comes out targeted towards the risk of COVID-19 to certain communities, the public perception and focus will be on the rebellious spirit of a that community. And not on other economic and social factors such as overcrowding, poor sanitation and the effects of poverty, which all have a role in the spread of a virus.

Article 2 of the UDHR states that we are all entitled to ‘the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status’

As stated earlier the first principle that governs the UDHR is in knowing that all human beings are born equal. But the 2nd core principle of human rights is in having a foundational understanding that rights cannot be discriminatory.

The issue with the UK in failing to provide ascertainment of certain rights is rooted in not having an equality as its foundational approach. So, how can you adequately provide healthcare, food, and adequate living for all if the principles of this country do not believe all deserve it.

The ‘Right to Food’ is an explicit example of this. In emergencies such as a pandemic the committee of Economic Social and Cultural Rights stated that is a state’s obligation to make sure food resources are available for all. Yet the government debated providing children access to free school meals over the holidays. It is understood that COVID-19 had an impact to many sectors including jobs being cut, schools being closed, but this measure has an effect on those most vulnerable in society i.e. children living in poverty. Closure of schools during pandemic is the difference between access to food for some children. Yet the government did not want to accept obligation to provide food for all based on their ideology regarding poverty. This decision was overturned after campaigning by Marcus Rashford a famous football player and public outcry. This, however, is the same government that endorsed food banks being set up for NHS staff key workers and their families, without the need for debate. This has a discriminatory undertone as it shows that providing food to those who are often ostracized by society (those that are poor) is not seen as a priority. Furthering a moral complex, the UK has in fulfilling obligations for people who they believe to deserve it.

In order for the government to recover from this pandemic it must acknowledge the disservice it has caused to minority and vulnerable groups in society. The government’s lack of proactive and targeted implementation for the future has led to frustrations, protests, more race reports from committee’s and an overall dissatisfaction no matter which political party you are affiliated with. As human beings our rights cannot be actualised until they are built into our systems. The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights states that ‘violating the right to health may often impair the enjoyment of other human rights, such as the rights to education or work, and vice versa.’ Therefore, in the government failing to secure the Right to Health they are at risk of creating further damage to people’s Rights to Work, livelihood and much more.

What can be learned?

Save your pennies for a rainy day – this sweet sentiment should be applied to how the NHS is built. They need to rebuild and restructure the healthcare system in the UK look at impact to years of mismatched budget spending and austerity cuts to the NHS has had on the system in order to provide adequate/ basic and non-discriminatory care.

They need to re-evaluate policy and laws in the UK that continue to discriminate access by certain groups. The UK need to have policies that protect and target the most vulnerable in society not harm them further. Example of harmful legislation passing of the 2020 Immigration Bill which gave powers to unjust deportations of legal migrants for sleeping rough. Now would be a great time for the Conservative government to pass S.14 of the Equality Act 2010. People need to feel they have access to justice and a legislative system that acknowledges the intersectionality of discrimination which can be found in S.14 Equality act 2010. If the state continuous to violate rights on the grounds of public interest it, should be my right to access the domestic law and have a judicial system that will understand discrimination on grounds of my position in society, be it gender, class or race.

COVID-19 has highlighted that in order for us to move forward the UK must not be complacent in its position on inequality and preventing access to the rights declared in the UDHR and until the UK can deal with that, we are at great risk of repeating history’s mistakes.

Tallulah Mbangweta is an undergraduate student studying for a Bachelor of Laws in the School of Law.