Dr Simon Willems, Lecturer in Art, argues that workplace wellbeing has been depoliticised by corporate culture, and explores how contemporary art can expose the hidden power structures behind wellness programmes.

How do we rethink wellbeing in the workplace and what can art add to this debate? Since the turn of the millennium, wellbeing has become a staple theme in organisations, in tandem with neoliberal ideals. This has instituted an ethos of self-regulation and personal responsibility, carrying the implicit message that if you are ill it is ‘your’ fault.

Yet artistic research has tended to splinter on the question of wellbeing. On the one hand, it gravitates towards wellness at large, addressing a culture of metrics and self-optimisation; on the other, it gravitates towards ‘immaterial labour’ – creative and emotional work that often goes unpaid – and assumes the lone worker in precarity.

Worthy though these pursuits are, what they obscure – what demands attention – is the reality that most of us work, in part if not entirely, in organisations and do so with others. My research aims to advance understanding of wellbeing as something situated in relationships as much as it is politics and economics, revealing where, as a narrative, it has been co-opted and depoliticised by market forces.

Beyond the zeitgeist

Workplace wellbeing is fundamentally a moral question – one that’s as much about imbalances of power and privilege as it is about what meaningful work might look like. By examining the strategies artists deploy and media that they draw upon, we can unpack how neoliberalism has coopted the language of ‘mental health’ and wellness. Even if, as curator Robert Leonard rightly notes, we should stay alert to how this fits within the wider wellness culture that surrounds us.

Art has a unique case to make in critically exposing notions of wellbeing which abstract employees from their needs and lived experience, treating them as tools for productivity rather than people. But, as Leonard suggests, this critical power is blunted if artists are downplayed and the reasons they make art undermined; if art is reduced to a therapeutic role for the sake of box ticking and securing funding.

As a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow based between Henley Business School and Reading School of Art, I’ve spent four years addressing these questions through an interdisciplinary lens, consulting with experts from fine art, social science, moral philosophy and digital humanities. The research covers topics such as mindfulness, self-tracking, gamification and institutional wellness – forming the basis of my forthcoming book, Rethinking Wellbeing Through Art: How Artists Critique Wellness Narratives in the Workplace (Palgrave Macmillan).

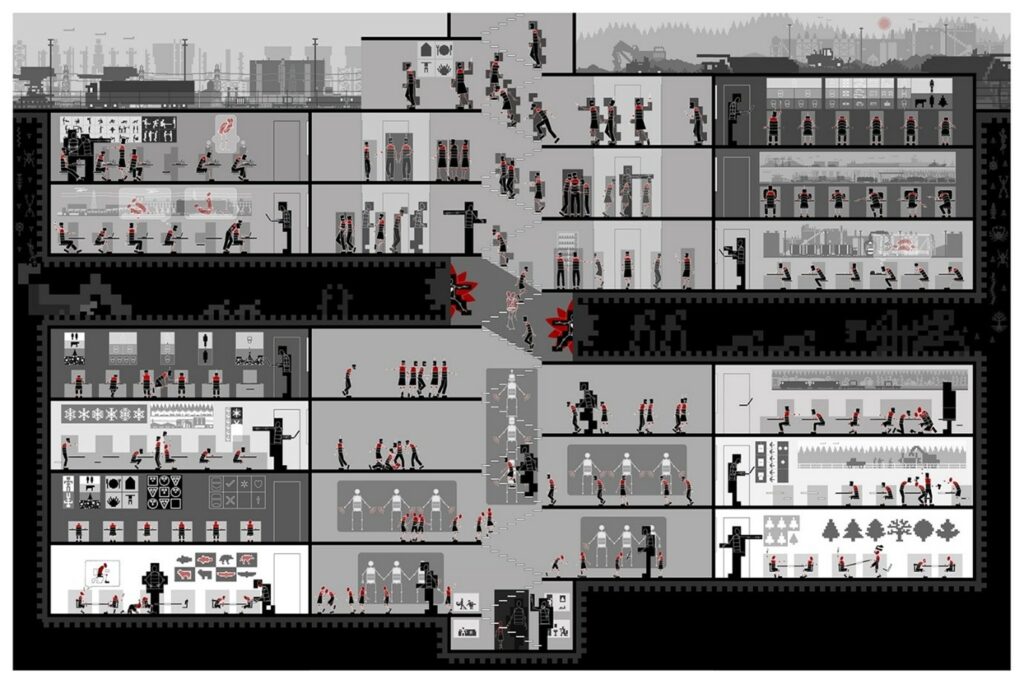

My collaborations throughout the project led to a two-day symposium and a group exhibition entitled HARDER, BETTER, FASTER, STRONGER at the Stephen Lawrence Gallery in Greenwich in July 2025. This provided an opportunity to evaluate workplace wellbeing from multiple perspectives whilst also considering, across disciplines, how the ‘therapeutic turn’ in organisations and the ‘turn to health’ in artistic production raises the stakes in recognising wellbeing as a political and ethical question.

Reclaiming ethics

Before the 2020 pandemic, a spate of exhibitions focusing on mental and physical health placed renewed emphasis on personal and collective wellbeing. Key survey-exhibitions such as Group Therapy at Frye Art Museum, Seattle (2018-19) and Hyper Functional, Ultra Healthy at Somerset House, London (2020) presented work that looked beyond the neoliberal obsession with individual wellness towards alternative solutions that take account of structural inequalities and social injustice.

This renewed focus on wellness and self-care was not only felt in curatorship, but also in public programmes, as museums hosted yoga and meditation classes, mindfulness workshops and other therapeutic activities to cushion the stresses of contemporary life. Yet what these developments lacked, whilst raising the question of wellbeing, was a deeper appraisal, as Leonard highlights: both of the political structures using wellness narratives in the production of art and its institutions, as well as a focus on how narratives of wellness play out, specifically in workplace contexts.

My research has similarly revealed that it is not enough to frame wellbeing solely in relation to corporate wellbeing programmes in which any assessment is limited to tertiary sector white-collar work and the knowledge economy. This is a point laid bare in Pilvi Takala’s film The Stroker (2019) in which the artist doubles-up as a wellness consultant employed to greet young entrepreneurs and startups in a trendy East London workspace. Contracted to assume intimacy as she works the floor, Takala’s arm-stroking efforts are radically reframed upon ‘greeting’ the cleaner, revealing the film’s hole, exposing precisely that strata of blue-collar work that props up ‘wellbeing’ as a white-collar narrative.

More than this, if we want to properly address the complex, overarching question of wellbeing – beyond a reductive therapy-infused proposition – the struggles for equality of women and marginalised groups must be critical to this undertaking. ‘Employee wellbeing’ infers both an undifferentiated mass and the abstract disembodied self, negating what Lisa Tessman aptly describes as the question of ‘burdened virtue’ afflicting these parties.

Education and health

So where does this take us? Thinking about what art contributes to the discussion is one thing; determining where it seeks real-world application is quite another. The fellowship has allowed me to build an interdisciplinary network of scholars and practitioners, as the Greenwich symposium and exhibition demonstrate. But what matters most is where this leads.

The ongoing crisis in UK Higher Education is a good place to start. When surveyed in 2022, 60% of UK academics expressed a desire to quit within 5 years. Yet no society can flourish in a culture which reduces education to a business, treating it purely as an investment that must deliver financial returns.

I believe that contemporary art is uniquely positioned to expose, interpret and communicate systemic harms to physical and mental health in Higher Education. I’m now developing a project in which artists will work directly with university staff to tell their employee wellbeing stories, alongside embedded community-based social practice in mapping out and translating their lived experiences.

Bridging art and management studies, my research challenges how corporate wellness narratives have stripped workplace wellbeing of its political and ethical meaning. Workers are human beings, not resources to be optimised, yet this is precisely what gets lost in the language of self-care and resilience. Where wellness programmes ask us to meditate our way through impossible workloads, art exposes the structures that create those conditions in the first place. That’s why we need artists in this conversation – to cut through the corporate speak and reclaim workers as individuals within a culture of short-termism and competition.