So here we are again, after a weekend of press and parliamentary misogyny, the subsequent outrage will inevitably simmer down and go away until the next time…and the next time… and the next time.

Angela Rayner called out “sexism and misogyny” in politics, after the Mail on Sunday claimed that she crosses and uncrosses her legs during prime minister’s questions to distract Boris Johnson. The report was universally condemned by Johnson and MPs from across the House of Commons. The Mail on Sunday reported that an unnamed Conservative MP said Rayner’s actions constituted “a fully clothed parliamentary equivalent of Sharon Stone’s infamous scene in the 1992 film Basic Instinct”. I am not going to include a photograph of Angela Rayner’s legs here, rather her own take on the issue (forgive the awkward image but I needed to crop the inevitable male comment).

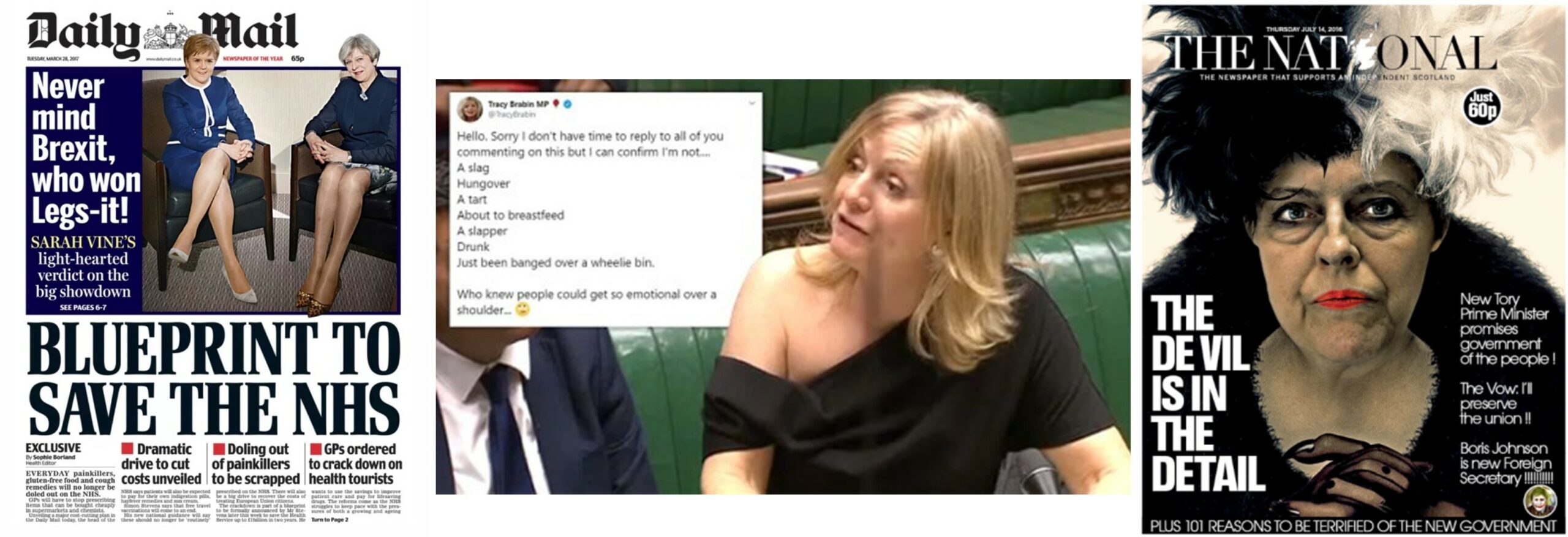

Of course, she is right, from the outset women in the House were considered an aberration, a passing phase, a temporary blip that would go away allowing business to return to normal. That clearly didn’t happen and while we may not yet have equal representation in parliament, things have improved. Unfortunately, the misogyny that lies just below the surface has not altogether, it is very often simply shielded. Edwina Curry’s confident statement that women were no longer at any disadvantage over men continues to be risible. From Sturgeon and May in ‘Legs-it’ to Tracy Brabin’s off the shoulder top, the obsession with women’s appearances and how this indicates or constructs their sexuality is never ending. Let’s not even go there with Diane Abbott who regularly receives more than half the abusive Twitter trolling of all women MPs.

Beyond comment on women’s sexuality, in 2016 the outrageous representation of Theresa May as Cruella Deville by the Scottish nationalist newspaper, The National, evidences the media continuing to question that second prong of femininity – women’s ‘special feminine qualities’ as wives and mothers and the fact that women who do not openly exhibit these are also questioned and pilloried.

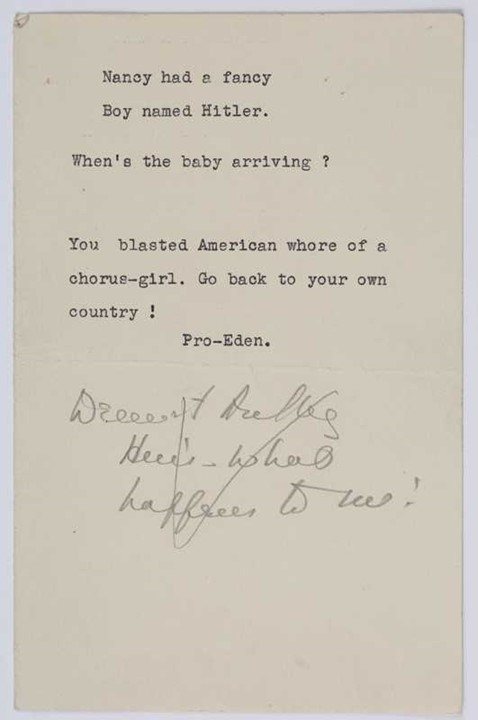

Thus it is and always has been. The first woman took her seat in Parliament against a maelstrom of press comment. Press comment was intrusive, invariably hostile and focused on her marital status and dress. Nancy Astor was elected to parliament for Plymouth Sutton at a by-election in November 1919 replacing her husband who had previously been MP. She stood as a Unionist candidate though many in the party had reservations, including the Unionist Party Chairman, Sir George Younger, who felt that ‘the worst of it is, the woman is sure to get in’. She did get in and on 1 December 1919 when she stood at the bar in the House of Commons, Astor’s words as she took the oath was the first time a female voice had been heard in the Chamber. The Chamber was not full but the Manchester Guardian reported that the proceedings generated a ‘flutter of altogether pleasant excitement’ though Astor sensed an undercurrent of nervousness: ‘I was deeply conscious of representing a Cause, whereas I think they were a little nervous of having let down the House of Commons by escorting the Cause into it’. Astor’s presence in the House had been commented on in The Times the day after her election. A woman MP, was a ‘tremendous breach in Parliamentary tradition’. The language used by The Times strongly suggested that Astor was an unwanted intrusion, an illegal intrusion and she was forcibly overcoming a bastion of male dominance. The notion of a woman had been ‘almost inconceivable’. Astor had to cope with a constant and insidious sexism that undermined her attempts to be taken seriously. She avoided comments on her clothing, by adopting a uniform of dark coat and skirt, white blouse and tricorn hat but she was less successful in evading the patronizingly flirtatious and ribald comments of her male colleagues.

Astor’s maiden speech in 1920 was in opposition to a proposal to relax wartime restrictions on opening hours for public houses. Sir John Rees, who was well aware of Astor’s abstentionist politics, concluded his speech by looking directly at her, and archly remarked:

I do not doubt that a rod is in pickle for me when I sit down, but I will accept the chastisement with resignation and am indeed ready to kiss the rod.

Astor wittily demurred, replying that Rees had gone ‘a bit too far. However, I will consider his proposal if I can convert him’. No such witticism is recorded for the occasion on which an inebriated Jack Jones, Labour MP for Silvertown, interrupted Astor. Refusing to give way, Astor told Jones he was drinking too much and should think of his stomach, to which he answered to loud guffaws, he would push his stomach up against hers any time she liked.

While the medium was different, the sexualised trolling was the same.

Possibly all of this may have been considered ‘understandable’ in the context of the interwar period BUT the insidious sexism that Astor experienced remains, overlooked and often sniggered at, over a century later. It might best be equated to the statement made by comedian Jo Brand on BBC One’s Have I Got News For You in 2017: within the context of the #MeToo movement and in the wake of a series of resignations over what Sir Michael Fallon had described as behaviour that had “fallen short” of expectations, the all-male panel discussed the issues raised. With a smirk, regular team captain Ian Hislop described some claims of harassment as “not high-level crime … compared to say Putin or Trump”. Brand’s response was measured but spoke volumes:

If I can just say, as the only representative of the female gender here today, I know it’s not high level, but it doesn’t have to be high level for women to feel under siege in somewhere like the House of Commons. And actually, for women, if you’re constantly being harassed, even in a small way, that builds up and that wears you down.

Questions of severity and degree are, for most of us, an ‘insidious’ undermining of sexual harassment which will never change until we have an equal power balance in society and in Parliament. All of this said, and with absolute support for Angela Rayner, not long ago, Rayner could not or would not define what was meant by ‘woman’, here is the reality of being a woman, Rayner can’t always have it both ways.

Dr Jacqui Turner is Associate Professor in Modern History. You can find out more about Dr Turner and her work at Dr Jacqui Turner – History (reading.ac.uk) and her work on the centenary of women in parliament at Astor 100 – Celebrating 100 years of women in parliament (reading.ac.uk).

For more historical comment on women MPs, the press and their appearances see:

Cowman, K., (2020) ‘A Matter of Public Interest: Press Coverage of the Outfits of Women MPs 1918–1930’, in Grey D. and Turner J. (eds), ‘Nancy Astor, Public Women and Gendered Politics in Interwar Britian’, Open Library of Humanities 6(2), p.17. doi: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.583