This year marks the twentieth anniversary of World Blood Donor Day when the World Health Organisation (WHO) and its global partners join to celebrate the lifesaving work of blood donors. In this blog post, PhD researcher Tyler Horn highlights the importance of platelet donation, since this can be done more frequently than whole blood donation and each donation can treat up to 12 children or 3 adults who have blood clotting disorders, are undergoing surgery or are in intensive care.

For platelet donation, blood is taken, the platelets removed and then the other blood constituents, such as red blood cells, are returned to the donor. Because the other blood components do not become depleted, donations can be more frequent, and one donor can help many people.

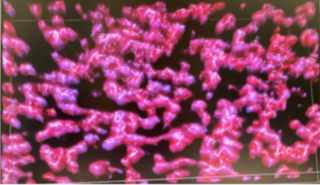

Platelets are unique cells within the blood; they are tiny cells whose primary function is to help prevent bleeding after an injury. To do this, they are covered in receptor proteins which can detect damage sites after an injury. Once the damage has been detected, the platelets can stick to the damaged area and start attracting other platelets to stick to the area, forming a blood clot and preventing further bleeding. Although this is the best-known role of platelets, they also have secondary functions in inflammation and other diseases.

Pictured: A 3D projection of platelets thrombi formed in vitro using confocal microscopy by Kirk Taylor.

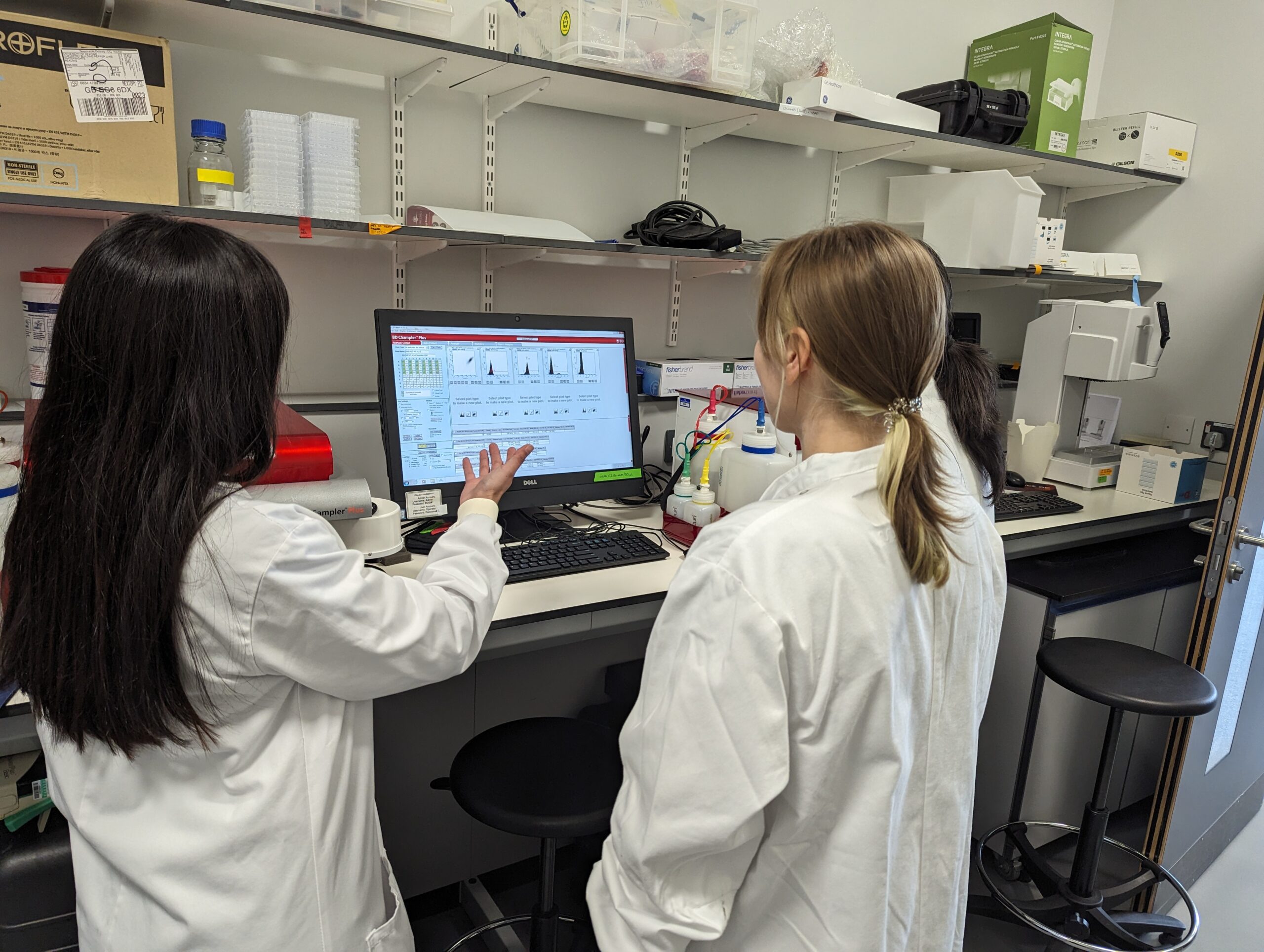

Our understanding of platelet function is constantly evolving, facilitated by researchers across the world. The Platelet Research Group at the University of Reading focuses on the underlying molecular mechanisms that control platelet function in health and disease. To do this we use a series of cutting-edge techniques such as flow cytometry (a lab test used to analyse, count and characterises cells or particles) and confocal microscopy (to generate high-resolution images of material such as platelets stained with fluorescent antibodies).

The Group has strong links to our wider community to harness the knowledge and experience of our local experts. For example, we work with the Royal Berkshire NHS Foundation Trust as part of the Health Innovation Partnership (HIP) between the university and the hospital to further research and improve clinical care excellence.

One of the research projects facilitated by the HIP is a study of platelet function in critical illness and liver disease. Patients with liver disease are prone to both thrombosis (clotting which blocks blood vessels) and bleeding complications but the relationship between patients and these events is more complex than simply having too many or too few platelets.

Thrombosis and its subsequent blocking of blood vessels can cause heart attacks or strokes. Or the bleeding consequences of liver disease can make diagnostic procedures such as biopsies tricky. Therefore, in this study, we are attempting to examine the function of platelets in patients to see if there is a difference between healthy individuals and those with liver disease. Once we have categorised function in this way, we can further investigate platelet function changes based on disease state and organ dysfunction.

Pictured: Left Maria Diaz Alsonzo and Right Dr Valentina Shpakova analysing flow cytometry data.

This information is vital as by understanding what changes and by how much in these patients we can use this information to help us treat symptoms or implement early diagnosis of patients who are likely to experience thrombosis or bleeding.

The Reading Platelet Research Group aims to further our understanding of platelet functionality and use this knowledge in conjunction with our patient research to improve our understanding of disease. By furthering our understanding of platelet function, we hope to launch further research into methods to better treat these patients improving clinical outcomes as we move towards a world of personalised medicine.

Tyler Horn is a PhD researcher working alongside Dr Craig Hughes and Professor Jon Gibbins from the Reading Platelet Group and Dr Matthew Frise and Dr Liza Keating from the Royal Berkshire Hospital as part of the HIP study on platelet function in critical illness and liver disease.