The NHS turns 70 this year, giving us the chance to appreciate the fact it is there to turn to whenever we get ill. But what did people do before the NHS and the luxury of modern medicine? University of Reading historian Dr Hannah Newton reveals her findings from studying diaries and letters written by Early Modern families who faced serious diseases armed with little more than their faith.

Cancer survival has doubled over the last 40 years, and death rates from stroke have halved since 1990. These positive trends are reflected in the upsurge of survivor stories in social media, where individuals broadcast their experiences of illness and recovery, and describe how the close shave with death has changed their outlook on life. ‘I don’t let little things get on top of me as much anymore’, reflects Keith Hubbard, a musician from Merseyside, 14 years after treatment for prostate cancer.

We might assume that this is a recent phenomenon. In more distant times, when epidemics were rife and medicines ineffective, it would seem likely that death was the only possible disease outcome. However, a foray into the diaries and letters of seventeenth-century patients and their families reveals a happier history. My new book, Misery to Mirth, shows that getting better was a widely reported occurrence at this time, and one which gave rise to emotionally-charged outpourings comparable to those produced today.

Closest to my heart is the story of 11-year-old Martha Hatfield from Yorkshire, which I encountered while researching for a previous book, The Sick Child. Martha was diagnosed in 1652 with ‘Spleen-wind’, a disease characterised by vomiting and convulsions. For nine months, her family was ‘continually under sadnesse’; they longed for God to ‘ease…her pain, [so] that [their] eares…might not be filled with such dolefull cries, nor their hearts with those fears’.

One December evening, Martha suddenly felt strength returning to her body. She ‘rejoyced…with laughing’ and ‘clasping her armes about her [mother’s] neck’ in an embrace. The next morning, Martha ‘took some food without spilling’, and told her parents she’d had ‘a very good night’. Later that day, her older sister Hannah, who had been ‘very tender of her’ during her illness, ‘took her up, and set her upon her feet, and she stood by herself without holding, which she had not done for three quarters of a year’.

Over the following weeks, Martha ‘encreased in strength’ beyond ‘all expectation’, and finally announced, ‘me is pretty well, I praise God…I am neither sick, nor have any pain’. A thanksgiving day was arranged to celebrate Martha’s recovery. One of the guests recalled that the sight of Martha coming ‘into the Hall to…welcome us…was wonderfull in our eyes, so that our hearts did rejoyce with a kind of trembling’.

Martha’s story was published by her uncle, the Sheffield minister James Fisher, to encourage others to trust in God’s capacity to heal the sick. It depicts recovery as a ‘happie motion’ from anguish to elation, a trajectory marked and measured by a number of key milestones, such as sleeping through the night, eating solid foods, and standing unaided. The account inspired the subject of my book not only by revealing that recovery was thought to be possible in early modern England, but by showing that descriptions of this outcome of illness have the potential to shine light into practically every corner of life in the past, from sibling relationships to breakfast routines.

Designed to rebalance and brighten our impression of premodern health, the book takes three perspectives: the first is medical, asking what doctors and patients meant by recovery, and how it was thought to happen. People believed their bodies contained a divinely endowed healing agent called ‘Nature’. The precursor to the concept of the immune system, Nature was personified as a hardworking housewife, who removed disease through processes that resembled cooking and cleaning: the ‘concoction’ and ‘expulsion’ of the toxic substances that were believed to cause illness – the ‘humours’.

Doctors assisted Nature by giving medicines designed to expel these humours, such as laxatives. Once the bad humours had been removed, the next stage of recovery could occur: the restoration of strength (convalescence). This was achieved through eating easily digestible foods like chicken broths and possets and getting plenty of sleep – similar to today’s convalescent care!

The second perspective taken in the book is from patients themselves. Recovery was often experienced as a wonderful transformation from ‘sickenesse to health…from sadnesse to mirth, from paine to ease, from prison to libertie, from death to life’.

Patients enjoyed the exquisite ease of abated pain, and cherished the freedom and sociability that came after the spell in the ‘lonely prison’ of the sickchamber. They took particular satisfaction in being able to carry out simple actions that prior to illness would have generated no comment, such as getting dressed. Claver Morris, a Dorset doctor, recorded that after his fever in 1720, ‘I got up…and put on everything excepting my shoose, & completely dress’d myself in 2 minutes, by my wife[’]s watch!’ Recovery was also a deeply spiritual experience, since it was believed to be ordained by God.

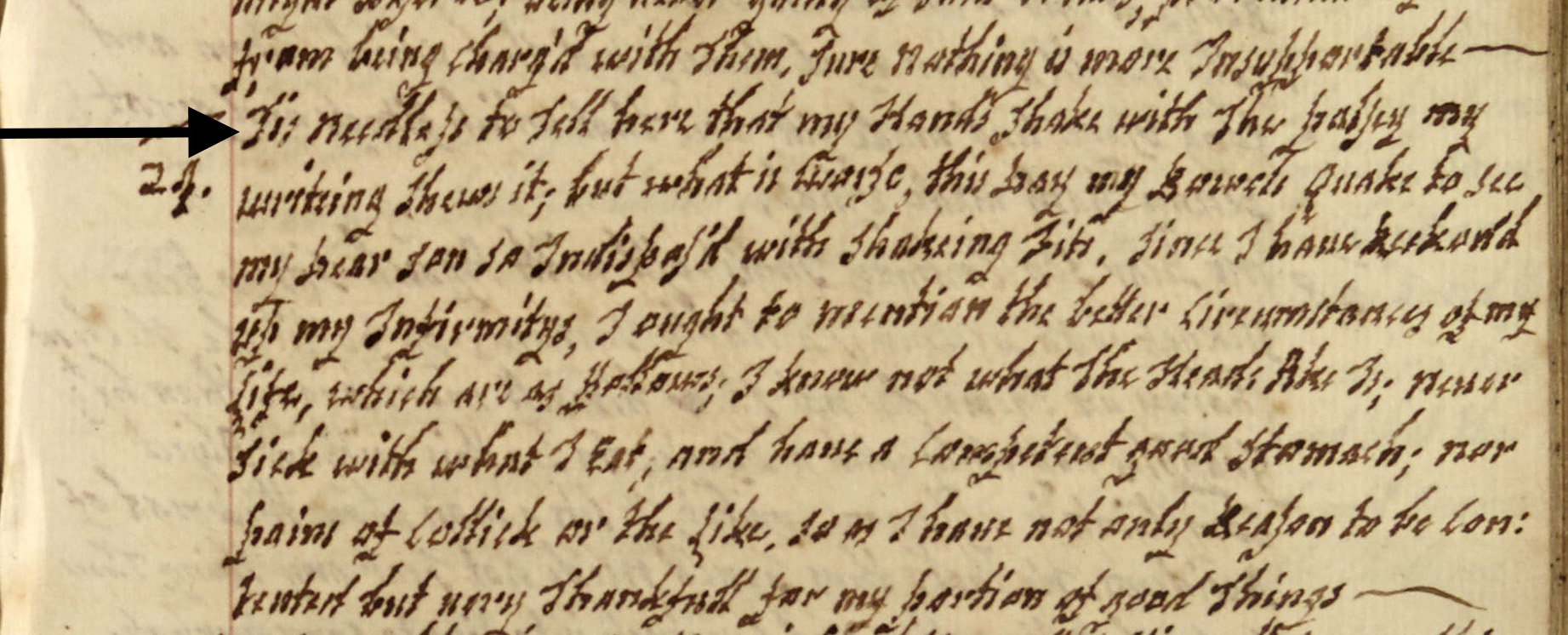

The third perspective is that of family and friends. I show that loved ones usually shared the feelings of patients, undergoing a dramatic transformation from agony to ecstasy. When his dear friend Robert Paston escaped death in 1675, Dr John Hildeyard told him, ‘My griefe[s]…are vanguished and…wholy swallowed up into joy’. This sharing of experiences – known as ‘fellow-feeling’ – was physical as well as emotional, since relatives claimed to share the patient’s pain during illness, and ease upon recovery. Modern neuroscientists wouldn’t be surprised – functional neuroimaging studies show that the ‘pain areas’ of the brain ‘light up’ when you see someone else in pain.

Although the book is mainly a happy history, it doesn’t ignore the gloomier side. Like today, getting better could take ages, and of course, not everyone made a full recovery. Nor did getting better always follow a linear motion: patients were ‘tremblingly afraid’ of relapse, and worried that the smallest action could rekindle sickness. For those who had longed for heaven during illness, survival could even be a disappointment! The minister Oliver Heywood reflected in 1691, ‘When many judged me a gone man, I was afraid it was too good to be true’.

To end we return to Martha Hatfield. As with modern survivors, Martha found that her recent sickness put life’s troubles in perspective. Before her illness, she been ‘much inclined to sadnesse and fretfulnesse’. From the time of her cure, she ‘walks on with much cheerfulness…[and] abundance of peace’, because she now knows that whatever ‘new Stormes’ await her, God will ‘come with healing under his wings’.