Medieval people have a reputation for being superstitious – and many of the supernatural phenomena found in the pages of medieval chronicles, miracle stories and romances are still alive in modern culture. Think ghosts, werewolves, demons, vampires, fairies and witches. But while (almost all) people today regard these beings as entirely fictional, many medieval people believed in them.

Christian theologians accepted the existence of the supernatural, categorising such beings broadly as “fallen angels” who viewed humanity as a battleground in their ongoing conflict with God. Their enormous power meant they could even appear as deities, including the pagan gods and goddesses – they were seen to take on a monstrous appearance mainly when claiming the souls of the damned or being defeated by a Christian leader.

The smaller and less powerful supernatural creatures known in Old and Middle English as “elves”, however, were seen to have less straightforward explanations.

Elves, fairies and sirens

Medieval elves were not usually as powerful as the glamorous beings envisioned centuries later by J.R.R. Tolkien. They merged with demons in some accounts and with fairies in others.

For the 13th-century English priest Layamon, it was elves (alven) who gave King Arthur magical gifts and who, in the form of beautiful women, carried him away to the mythical island of Avalun to heal. However, Layamon was careful to say that this was the belief of “the Britons” (Celtic people), which he was simply recording.

Fairies first appeared in French-language accounts and quickly blended with other categories of supernatural being. They were apparently more human in appearance than elves, though wings were added later.

They formed one category of the large group of tempting, supernatural female creatures who lured human men into dangerous relationships. Perhaps most famous is the fairy Melusine, who was strongly linked to water.

Melusine was half-human, half-serpent and was both beautiful and powerful. She brought prosperity and numerous sons to her human husband, but forbade him to see her at a specified time (Saturdays). When he broke his promise, Melusine’s true form was revealed, and she left forever.

It is unclear whether the chroniclers and readers who enjoyed such stories entirely believed them, but it seems likely that fairies were considered more real in the middle ages than now.

Medieval abductions and miracles

For medieval people, elves, fairies and sirens inhabited the ambiguous territory between fact and fiction. The same may be said of mysterious beings who abducted unsuspecting humans, often women, and carried them off to strange and frightening regions. Those who allegedly reported these experiences believed them to be real, although they were condemned as demonic illusions by moralists.

Being taken high above the Earth is a recurring theme in medieval writing, including tales of witches deliberately flying on the backs of animals. These abduction tales could be compared to modern accounts of alien abductions.

While tales of abduction by fairies were sometimes dismissed as delusions, stories of saints’ miracles and natural marvels were usually accepted as true. It might be tempting to compare the powers of miracle-working saints with those of modern superheroes – but miracles were considered overt demonstrations of the power of God, whereas superheroes tend to result from scientific or technological extremes.

A particularly sensational example was recorded in the Life of St Modwenna (an early Irish princess and abbess), written by the abbot Geoffrey of Burton circa 1120-1150. In his account, two tenants of Burton Abbey stirred up a violent feud between the abbot and Count Roger the Poitevin. The troublemakers died suddenly and were buried in haste, but apparently reappeared at sunset carrying their own coffins, before transforming into terrifying animals.

These revenants (spirits or animated corpses) reportedly brought death to the village – only three people were left alive. When the graves of the runaways were opened, they were found to be bloodstained but intact. A formal apology to the abbey and the saint was followed by ritual dismembering of these corpses and burning of their hearts. This apparently led to the expulsion of an evil spirit and the recovery of the surviving peasants.

Natural marvels

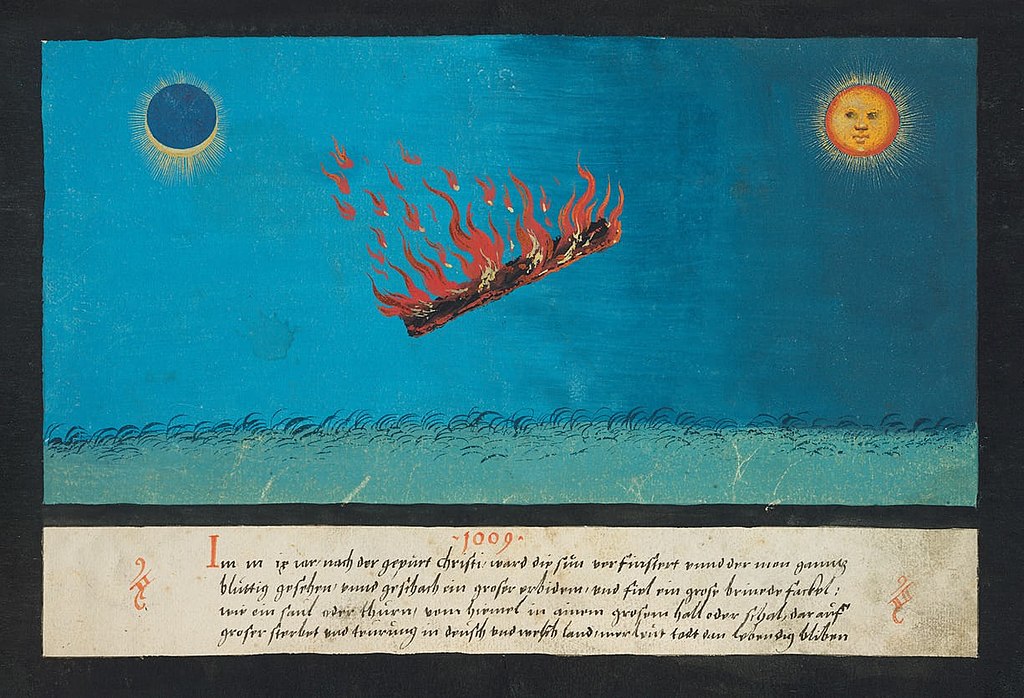

“Natural marvels” were medieval phenomena which were accepted as parts of God’s creation, but could not be scientifically explained. Many of the creatures found in bestiaries (medieval encyclopedias of animals both real and mythological) fitted here, such as dragons, unicorns and basilisks.

Dragons and unicorns remain popular fantasy characters today, but basilisks are less well known – although a giant one once proved a fearsome opponent for Harry Potter. Basilisks were said to be so poisonous that their scent, their fiery breath and even their gaze could kill. They were attested not only by bestiaries but by the Roman philosopher and botanist Pliny in his book Natural History (circa AD77). They were found in the province of Cyrene, in modern Libya.

Similarly, different regions of the Earth were characterised by natural marvels recorded in works such as priest and historian Gerald of Wales’s book, The History and Topography of Ireland (1185-88).

Gerald noted that some readers would find his stories “impossible or ridiculous”, but testified to their accuracy. They included strange islands where no female creature could survive and nobody could die a natural death, as well as strange creatures and humans forced to transform periodically into wolves by the power of St Natalis (an Irish monk and saint).

Medieval people believed in a wide array of supernatural beings. While today we mostly see them as the stuff of nightmarish fiction, our enthusiasm for this diversity hasn’t waned – just look at the breadth of supernatural costumes on display every Halloween.

![]()

Anne Lawrence-Mathers, Professor in Medieval History, University of Reading

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.