On Friday 5 March, the Stephen Dwoskin Project, led by Rachel Garfield, head of the School of Art, will mount the first in a series of screening and discussion events, Dwoskin, Disability and… Accessibility: Face of Our Fear.

Dwoskin was an experimental filmmaker who came to London from New York in 1964. He had contracted polio in childhood and walked with crutches; later he would use a wheelchair. Dwoskin was wary of being seen as a ‘disabled filmmaker’, but disablement became a subject of his always very personal films during the 1970s, from a variety of perspectives.

The film we are showing, Face of Our Fear, was made for Channel 4 in 1992, for the launch night of its season ‘Disabling World’. Outwardly a documentary about media representations of disablement – using clips, talking heads, and a voiceover – it is as personal as any of Dwoskin’s other films.

The event has grown out of our research in the Dwoskin archive, which is held by UoR Special Collections, and contains diaries, letters, all manner of documents, and thousands of still negatives, ones of which – scanned by archivist Jennifer Glanville – is shown below.

Dwoskin’s papers enable us to chart the development of Face of Our Fear in forensic detail, from its genesis in his failure to convince Channel 4 to make a film titled Diary of a Wheelchair, described in this blogpost, to the minutiae of post-production.

In particular, the Face of Our Fear papers enable us to tell a story about Dwoskin’s relationship with technology, which was always intimately bound up with questions of mobility and accessibility. His last films, from the turn of the millennium to his death in 2012, made early use of portable digital cameras and home computer editing programmes.

Face of Our Fear, however, was the first of his major films to be shot on video, specifically Hi8 video. Dwoskin’s editor Anthea Kennedy recalls: “video was easier for Steve because it’s less physical – more button pushing”. They would assemble a rough cut on video, then transfer the material that would go into the finished version on to 16mm film, with which Anthea would produce the fine cut; Dwoskin had both video and film editing equipment in the same room at his house in Brixton.

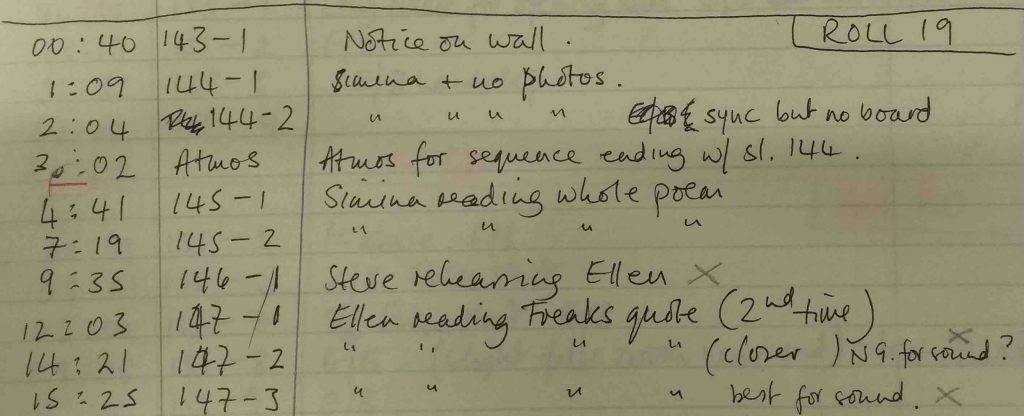

The evolution of the film from rough to fine can be tracked through Anthea’s minutely detailed logs of each shot, first on video (with timecodes), then on film (with each frame identified by number). Timecodes also figure at an earlier stage: to illustrate its thesis, Face of Our Fear includes footage from a number of Hollywood productions, and Dwoskin’s notebooks include his notes, with timecodes, on a number of these, including films that he used – such as Freaks (1932), and those that the rights-holders would not permit him to use, such as Coming Home (1978).

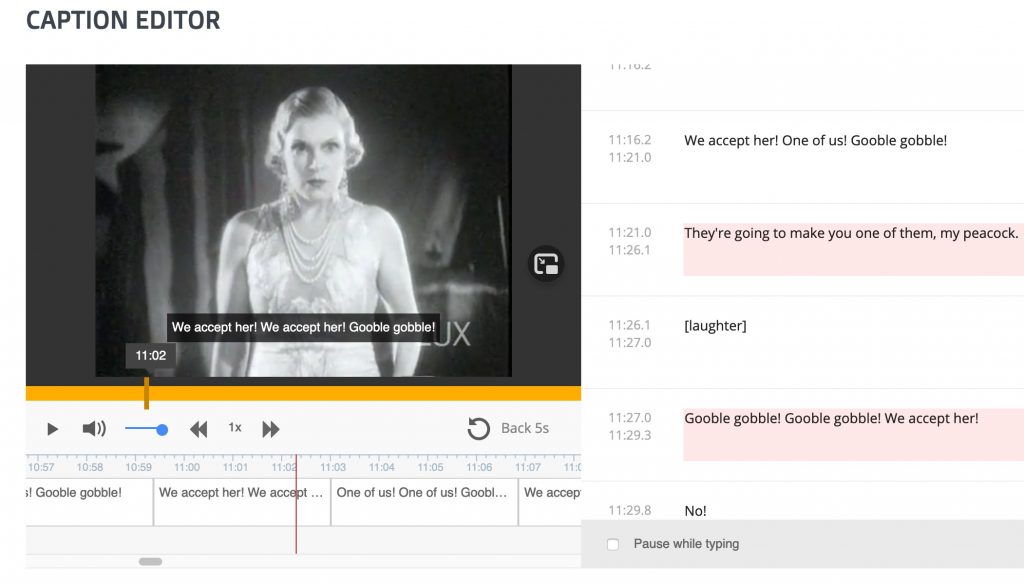

To bring things full circle, timecodes loom large in what might be called the post-post-production process of preparing the film for the screening. The discussion after the event will be BSL-interpreted and live-captioned; meanwhile I have been arranging closed captions for Face of Our Fear. The initial work is done by an online business, GoTranscript, which generates an .srt file, and provides an online platform where its customers can do further work on it, correcting the words and fine-tuning the timings. I’ve been able to draw on the materials in the archive, which include what amounts to a partial script, to get it right.

Captioning is incidentally a good way to research a film up close, since it requires you to attend to every shot, and the key question of how to make it clear who is speaking – especially, as in this instance, when there is a voiceover – makes you think about how sound and image relate to one another. It also, inevitably, generates more research questions. Face of Our Fear was originally broadcast with Teletext subtitles – but was Dwoskin involved in producing them, and were they somehow preserved?

Captioning is incidentally a good way to research a film up close, since it requires you to attend to every shot, and the key question of how to make it clear who is speaking – especially, as in this instance, when there is a voiceover – makes you think about how sound and image relate to one another. It also, inevitably, generates more research questions. Face of Our Fear was originally broadcast with Teletext subtitles – but was Dwoskin involved in producing them, and were they somehow preserved?

Dwoskin, disability, and… accessibility: Face of Our Fear will take place on the evening of Friday 5 March 19:00, you can book tickets for this free event through Eventbrite.

More information can be found on the Stephen Dwoskin Project website.

Henry K. Miller is a Post-doctoral Research Associate in the School of Art.