I recently completed the production of my first film. I started work on it last year following a successful bid to a Centre for Film Aesthetics and Cultures (CFAC) funding call for prospective film makers, in which applications were actively encouraged from those new to the field. As Outreach Lead in the Department of English Literature, I welcomed the opportunity to try and communicate complex ideas to a wider audience through a medium in which I had a long-standing research interest, but no practical experience.

I have recently published on the ideas of the controversial Slovenian philosopher and cultural commentator Slavoj Žižek, questioning his rejection of both close textual reading and identity politics. Žižek has a global following outside of academia and has been dubbed both the “Elvis of cultural theory” and “the most dangerous philosopher in the West”. Best known for his provocative insights into contemporary politics and culture, his style is infamously idiosyncratic. Žižek has found a significant audience for his ideas due to his communicative brilliance: his films feature highly entertaining yet seemingly shambolic monologues, visual jokes, irreverence, and weird connections between high and low culture. As I began to think about how I could utilise some of these techniques to create a film that could compete with Zizek’s own in a YouTube setting, the idea of ‘Žižek’s Sniff’ came to me. As strange as it may seem, Žižek is perhaps more famous for sniffing than he is for his controversial views. A recent YouTube video that edited out everything from his films other than a succession of sniffs gained half a million hits. Might I explain and critique Žižek’s philosophy in an entertaining fashion through talking about his sniff…?

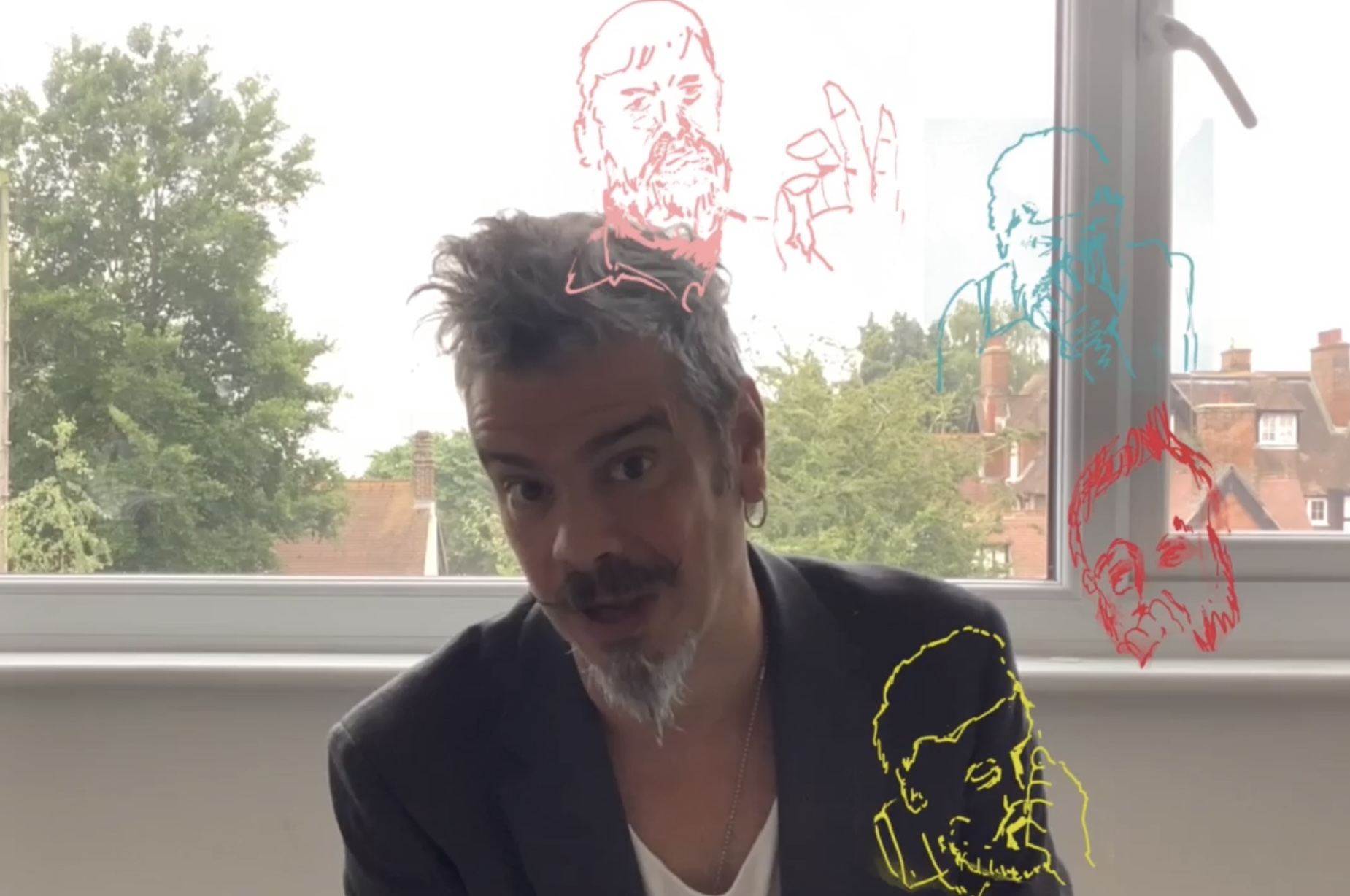

Talking to Adam O’Brien, one of the Co-Directors of CFAC, confirmed for me the possibilities of such an approach, and he helped me make a number of key decisions. This was to be a ‘laptop documentary’, one that would make a virtue of the limitations caused by the national lockdown we were experiencing at the time, my budget, and my film making experience. It would keep to a run-time of 8 minutes to ensure the non-specialist intended audience kept their interest throughout, and it would be shot ‘to camera’, with me taking on a Žižekian role as ironic narrator.

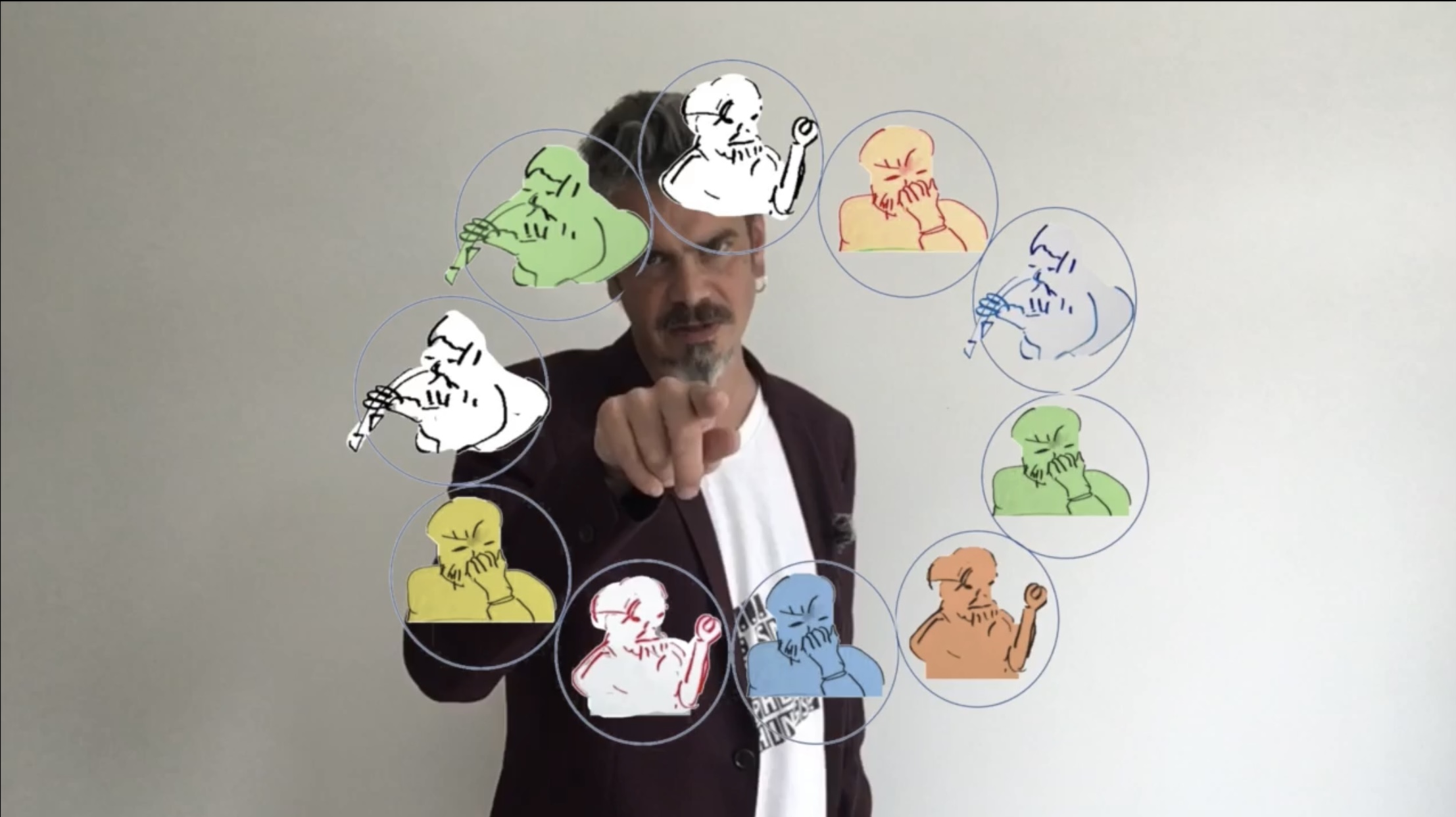

My initial attempt at a script was too long: the opening section explaining Žižekian philosophy alone lasted 10 minutes. I realised, however, that this explanation was already something of a critique, and not only because of the irreverence of the sniff. In explaining Žižek, I was offering my own take on what was most important about his philosophy, and subtly refiguring some of his most famous ideas. I gained School funding to work with a script editor with a background in Žižekian philosophy, Ting-Fang Yeh, and we came up with the idea of printing a succession of t-shirts for me to wear that included more critical questions on them. These run through the film like footnotes. We also worked on incorporating something of my seminar room teaching-style that often features faux-naive drawing on whiteboards to explain ideas. As well as hand-drawn animations, we also worked on visually exciting ways to connect the various sections together, including a running gag about encountering various things that would make me sniff (cats; cut grass; an open hoover bag…). I managed to film all the content in my house, a nearby field, and a University office.

The editor of the film, Hsin Hsieh from the Department of Film, Television and Theatre (FTT), helped turn the script into a film. Adam was right: the low-fi aesthetic played to our advantage. I recorded the whole film on an iPad using a £20 microphone that surprised us by working as well outside as it did inside. Hsin smoothed out differences in sound and colour post-production, and wove our crude animations and drawings into the fabric of the film. The major challenge was organisational. I broke the script down into individual sequences, planning around the weather, availability of props, and whether Ting-Fang and I were happy with the script. There are only a couple of moments in the film where there are issues with the end of one scene not quite setting up the next: occasionally my intonation and eye-line is off, and there is one transition from a bathroom to an office, where the acoustics are noticeably at odds. Other than that, and thanks to Hsin’s skill, the process was surprisingly straightforward.

With the film now complete, I really look forward to its premiere. I am happy with it, but what will the intended audience make of it? Looking back, my focus was too much on making sure I could defend the film from potential Žižekian critiques. I felt the need to include certain sequences to prove I understood certain concepts. I should have focused instead on keeping the interest of my intended, non-specialised audience. I am a little worried that those who will get most out of the film will indeed be the Žižekians who were the only audience I didn’t really feel I needed to address – ‘ah’, I imagine them saying, ‘that’s quite a clever way of explaining the concept of “the object a” to a general audience…’

Dr Neil Cocks is Associate Professor of Literary Perspective and Head of Outreach in the Department of English Literature.

The Centre for Film Aesthetics and Cultures (CFAC) is one of the University’s interdisciplinary research centres.