Annie Ure was a pioneering British archaeologist and co-founder of our Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology. Ruth Lloyd created a biography of Annie as part of her UROP project last summer, and as one of its winners, she recently presented her work at the House of Commons. Here she tells us about Annie’s life.

Annie Ure (centre, back row) with an excavation team at Rhitsona in Greece, 1921.

Annie Ure was among the first female British archaeologists to lead an excavation in Greece. As an expert in Boeotian Archaeology (Boeotia was a region of both ancient and modern day Greece), she went on to co-found a museum with her husband and curated it for 54 years until her death in 1976.

She was born Annie Dunman Hunt, in 1893 in Worcester, the youngest of seven children. She attended Stoneycroft, a small boarding school for girls in Southport, where she met Nora Kershaw (later Chadwick) who became a noted Anglo-Saxon and Celtic historian. Annie went on to study Classics at the University College, Reading – which later became the University of Reading. She took external exams at the University of London and received an upper second-class degree in 1914.

War effort

After earning her degree, she taught for a short while at Stoneycroft before being charmed back to Reading’s Classics Department by her professor, Percy Ure, to complete a postgraduate degree. Soon Annie was required to assist Professor Ure with lectures after the other male staff were conscripted into the army for the war effort. In an audio clip from the Ure museum’s archive, Annie explained the circumstances in which she was recruited:

“The excavation at Lowbury was finished in July 1914. In August the First World War began… the men went off to the war. Few came back, the casualties were fearful. … All those I knew at all well got killed, except one.

Mr Atkinson joined up and was given a farewell dinner. … Later on they did want him, but he didn’t get a second farewell dinner.

As he had been out for some time at the British School at Rome, and spoke Italian fluently, we expected he would be sent to the Italian front as a liaison officer. Not a bit of it. … They sent him to a yeomanry camp in Kent…

After he had gone, Professor Ure was left with all the teaching…. Even with the valuable help of the classical tutor from Lady Margaret Hall who came over one day a week, it was impossible, and I was fetched back to Reading to help with the teaching and eventually to run the College library as well.”

After working with him for little under a year, Annie married Percy Ure in 1918.

In 1921 they travelled to Greece together to conduct an excavation at Rhitsona, in Boeotia, a site that Percy had previously worked on with archaeologist Ronald Burrows in 1908. They excavated the necropolis of what was thought to be the ancient Boeotian town of Mykalessos. During these excavations Annie kept meticulous diaries of their trips and recounted the richness of the graves, sometimes including up to 400 artefacts.

A museum is born

Returning to the University College, Reading, the Ures collated their findings from Rhitsona with those of Burrows. Their book Sixth and Fifth-Century Pottery from Rhitsona is generally considered to be one of the most extensive records of Boeotian pottery. Alongside their publication, the Ures established a museum at the University College, which held several small collections and donations of Greek and Egyptian antiquities. Annie became its first curator and served the museum for 54 years until her death.

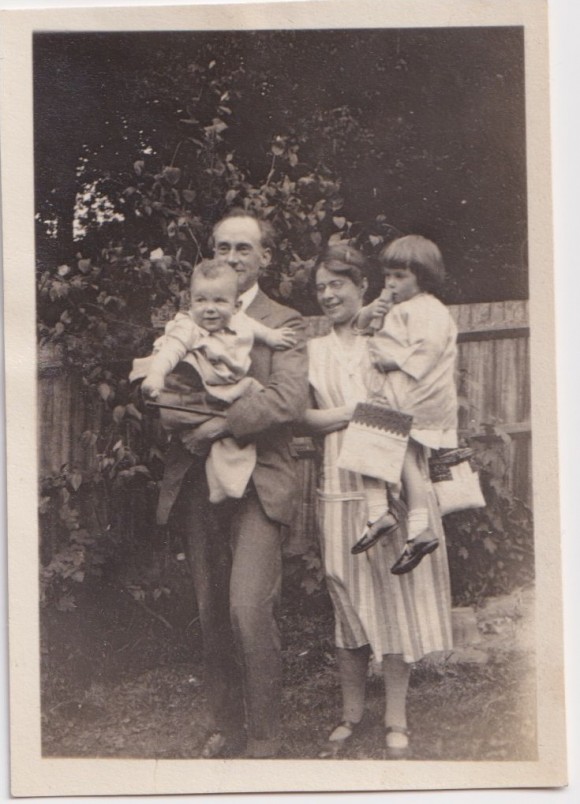

Together with her successful academic career, Annie had a highly fulfilling family life, having borne two children, Jean in 1924, and Bill in 1926. Despite her growing family, Annie never lost her passion for Boeotian and related archaeology or stopped working. In the early years of her children’s lives, Annie travelled extensively around Europe and the Mediterranean, visiting many museums in which she acquired knowledge and contacts.

She began teaching at the local Abbey School in Reading to fund her trips across Europe; her income significantly decreased after her husband’s death. In 1963 she retired from the Abbey School to teach at the University of Reading and continue to curate the museum.

In 1976, 10 days before her death, the University bestowed on her an honorary doctorate for her contributions, which spanned over 65 years. The museum, which was renamed the ‘Ure Museum of Greek Archaeology’ to honour Annie and her husband, is still open today at the University of Reading.

This post first appeared on the Trowelblazers blog. Ruth Lloyd is a student in the University of Reading’s Department of Archaeology and was one of two winners of last year’s Undergraduate Research Opportunities Programme (the other winner was Bilal Mohammed whose project focused on reducing medicines waste).

Ruth’s research project with Amara Thornton and Professor Amy Smith from the Ure Museum involved curating a timeline about the life of Annie Ure. Earlier this week, Ruth presented her work at the House of Commons at the annual Posters in Parliament event.