It’s almost 50 years since the BBC’s landmark Civilisation television series, which brought ancient worlds into the front rooms of millions. To mark the anniversary, Reading researchers recently spoke to BBC Berkshire about some unique local objects with a link to past civilisations across the globe.

Built to last

Professor Mike Fulford spoke about the wall which surrounds the ruins of the Roman town of Silchester, near Reading, and some of the building material artefacts found at the archaeological site.

“The wall dates from the late 3rd Century. It’s about a mile and a half all the way around. It’s a massive construction with a 10 foot thick base. In some places it’s still several metres high and you can see the materials it’s constructed from. The flint came from the chalk a few miles away and there are courses of stone slabs which help to bind the whole wall together.

Just think of the amount of work that was required to bring this together – the cart loads of flint being dragged along the roads, these stones coming from as far as 30 or 40 miles away, from Faringdon, up towards the Cotswolds. But it’s survived these 2000 years as a reminder of what the Romans contributed to this country in terms of the building technology and new ideas.”

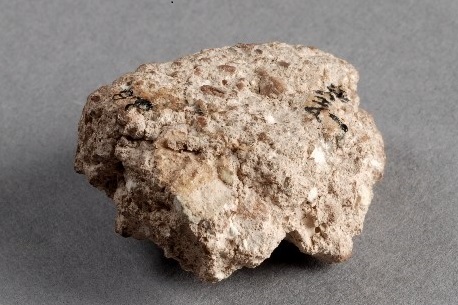

“Here is a simple piece of mortar, a piece of flooring, but what’s different about it is that it’s not just that it’s mortared together but they’ve built into it these little fragments of broken crushed brick, so gives it a reddish look. That was a very popular sort of material used for flooring or for surfacing around the baths and giving a waterproof surface.”

“Here is a simple piece of mortar, a piece of flooring, but what’s different about it is that it’s not just that it’s mortared together but they’ve built into it these little fragments of broken crushed brick, so gives it a reddish look. That was a very popular sort of material used for flooring or for surfacing around the baths and giving a waterproof surface.”

Earliest image of the ‘Queen of Heaven’

Professor Lindy Grant, from the Department of History, focused on a discarded chunk of stone from Reading Abbey which depicts the earliest known example of a popular medieval image – Christ crowning the Virgin Mary as the Queen of Heaven.

“This is a really important work of art here in Reading: it’s very battered looking capital made out of cast stone which probably comes from the cloister of Reading Abbey. What it shows is Christ crowning the Virgin Mary as Queen of heaven. It was made very early in the life of the Abbey – which was founded by King Henry I in the early 1120s. The cloister would have been built around that time, but this capital was probably unfinished or something went wrong with the carvings, so it got re-used as just a chunk of stone.

You have to look really carefully to see what’s there, but on one face of this capital you can see a woman sitting on huge medieval throne and next to her you can see the remains of a man, which is Christ. The woman is the Virgin Mary. She’s turning towards him and he is holding a crown above her head and they’re both sitting under an arch.

It is very battered but it’s very beautiful. She has a lovely rippling dress; it must have been silk or something like that and that the sculptor was trying to show that. It’s not only a magnificent object but it’s really important because this image of Christ crowing the Virgin became very widespread in Europe from the middle of the 12th century, and this is the first example that survives anywhere in the world of this very important Christian imagery.”

Stone Age Sonning

Professor Jim Leary talked about ancient flint stone axes found in the River Thames at Sonning and what we can learn from the people who made them.

“This is a Tranchet axe, a classic Mesolithic flint axe, also known as a Thames Pick because a huge quantity of them have been dredged from the Thames, possibly as ritual offerings.

It’s quite small, and would have been hafted [attached] into a long wooden haft and used for cutting down trees. Mesolithic people weren’t farmers, they were relatively mobile. But they would chop down trees which encouraged new growth and attracted new animals to the area. For people in this period the temperature is rising, they are just out of an ice age and the sea levels are rising – so the people making these artefacts were going through some pretty dramatic changes. There were changes to the types of trees, vegetation, animals because Britain was still joined to the continent throughout most of the Mesolithic period.

This illustrates the fundamental importance of archaeology – it provides us with a collective identity of why we’re here and how we move forward. We can learn, for example, how past societies have dealt with challenges such as climate change and migration and might learn something from it ourselves.”

Ancient pot from the Thames

Professor Amy Smith was interviewed by the river in Reading, and described an ancient Greek pot belonging to Reading Museum which was dredged up from the River Thames at Reading in the 19th Century.

“As far as I know this is the only Greek pot found in Reading. It’s one of at least four ancient Greek pots found in the river Thames. It could be, that, as it says in the Reading Museum records for this item, that some Victorian gentleman who got it on a Grand Tour of Europe probably threw it over the bridge and that’s how it ended up in the river – it was thought of as rubbish, maybe he was pretending to be an ancient Greek and drank wine out of it and threw it overboard.

“As far as I know this is the only Greek pot found in Reading. It’s one of at least four ancient Greek pots found in the river Thames. It could be, that, as it says in the Reading Museum records for this item, that some Victorian gentleman who got it on a Grand Tour of Europe probably threw it over the bridge and that’s how it ended up in the river – it was thought of as rubbish, maybe he was pretending to be an ancient Greek and drank wine out of it and threw it overboard.

The pot is of a type called a Kylix, to hold wine. It’s a pretty large by the standards of our wine glasses and looks to most people more like a bowl with a little stem on it and a big foot. It has a concave lip which makes a very prominent at the top a little deeper than some of the ancient Greek Kylices. In the middle it has a picture of a man, probably at a symposium, lying down drinking at a banquet – a red figure – but otherwise it just looks like a black glazed cup. Half of it is covered in really heavy sediment, river deposit that’s accumulated on the surface over these thousands of years. It’s from 500 BC, that’s when it was originally made.”

Image credits: Reading Museum