We all know that climate change is harming the planet – but what about us? Sarah Harrop reports on a recent public lecture by economist Professor Liz Robinson, in which she argues that curbing global warming is a win-win opportunity, not only to prevent environmental destruction but also to save lives.

What does the climate crisis mean to you? Perhaps you picture polar bears stranded on melting ice, Extinction Rebellion protests, forest fires in the Amazon?

We’ve known about climate change for decades. We know that it is killing wildlife, and that people in small island states are already losing their homes because of rising sea levels as the polar ice caps melt. But for many, climate change may still seem an abstract, distant problem for the future rather than one that affects us in the here and now.

The fact is that climate change is already here, and it’s not only harming the planet, but it’s also a major public health problem – particularly for the elderly and our children – the next generation.

The good news is that solutions for dealing with climate change are available. And, Professor Robinson outlined in her lecture, if we can curb climate change then we will also benefit our health – and that’s a win-win situation.

Heat and health

Heatwaves are often portrayed positively in the media – with pictures of people licking ice creams and sunbathing in the park. But for the young, the elderly and the ill, heatwaves are killers. Since 2015 there have been 3,500 extra deaths because of extreme weather events. This year in France, 1,500 more people died than they otherwise would have done thanks to extreme heat.

In wealthier countries we have the luxury of being able to adapt to extreme weather – altering our working conditions, setting up cool rooms, cranking up the air conditioning, putting in place phone response networks. But what about in low income countries where these options are less widely available?

When temperatures rise above 35 degrees C, we push our bodies to the limit. There are already places on earth where it’s too hot to live and there are cases of otherwise healthy people dying from excessive heat.

Wildfires are currently raging across California and New South Wales. Not only do fires kill people directly, but the smoke causes respiratory and cardiovascular problems. Again, the elderly and young are most vulnerable. Extreme heat events like these also take their toll on mental health – for example loss of homes, possessions or pets can cause depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.

There are lots of stories linking weather, climate and health – but what if they’ve always happened? How do we know that they are part of a wider phenomenon?

What policy-makers need is data and hard evidence for trends. They want to know if health is getting better or worse because of climate change. And if it is, how will these pressures impact health services and how can we plan for it? That is what The Lancet Countdown, a global study funded by the Wellcome Trust to which Professor Robinson’s research contributes, is working to achieve.

Global trends

We know that greenhouse gas emissions from industry, deforestation, agriculture and transport are causing average temperature of the planet to rise and also extreme heatwaves and altered rainfall.

This affects human health in many ways. For example, flooding can lead to more cases of bacterial diarrhoea as sewage mixes with drinking water, and higher temperatures increase the geographical spread of mosquitoes carrying dengue fever. Droughts cause crops to fail which leads to food shortages, and heatwaves and wildfires cause pollution that damages our hearts and lungs.

To track data over time, the authors of the Lancet Countdown look for indicators which can reveal a trend, or the lack of one.

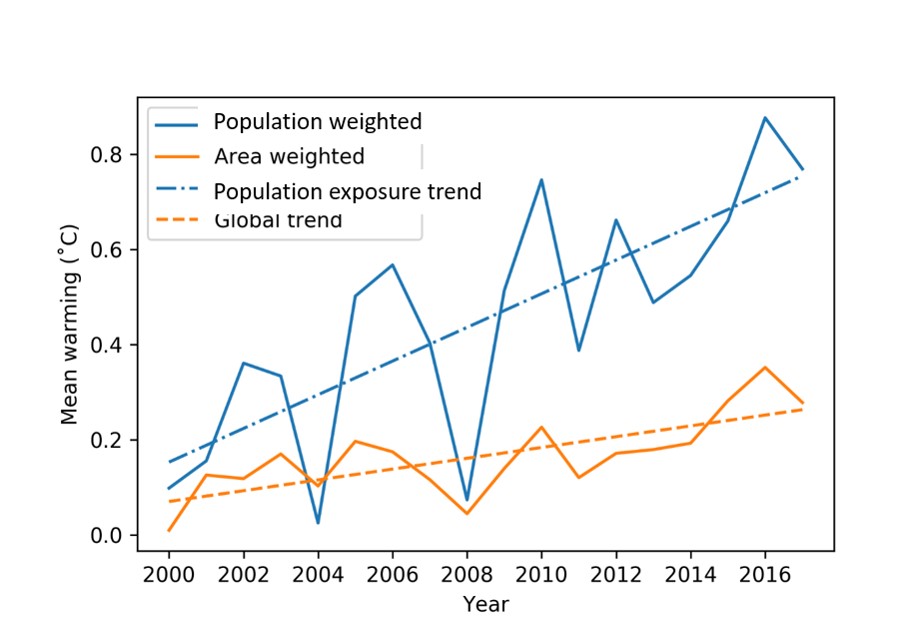

One such indicator is warming – particularly if it’s warming where people are living. This chart shows that while the planet is warming, the population exposure to warming trend is going up too. As people become better off, they move to towns, and urban areas are hotter because buildings and concrete absorb more heat. The data show a worryingly fast 0.8 degrees C rise in temperatures where people are living over the past 18 years.

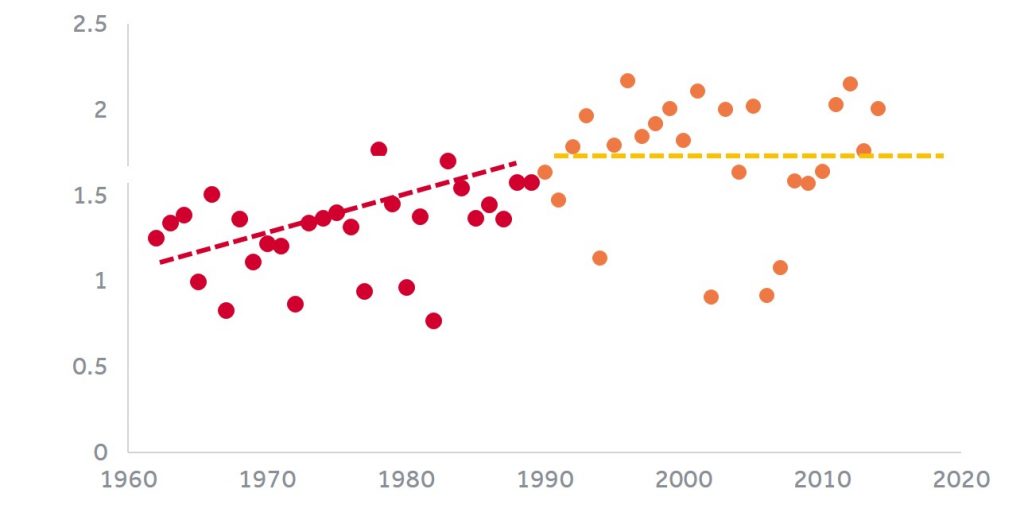

Indicators of crop yield potential are also concerning. Generally, over the decades, scientists would expect crop yields to improve through advances in technology such as irrigation and pest control. And warmth and carbon dioxide are both things plants need to grow – so wouldn’t it make sense that climate change is good for food production? But the data shows that crop yield potential has actually been falling since the 1980s.

In Australia, one of the world’s bread baskets, crop yields increased between 1960 and 1980, benefiting from the warmer temperatures. But then it stalled, and more crop failures are occurring because the excessive heat in recent decades has outweighed the benefits.

Why countries need to act

Individual countries can be reluctant to act because curbing climate change means that most of the benefits will be felt by others, whilst it bears the costs. Countries point the finger at each other, nothing gets done and we continue on our current trajectory towards a 3 or even 5 degree average temperature rise.

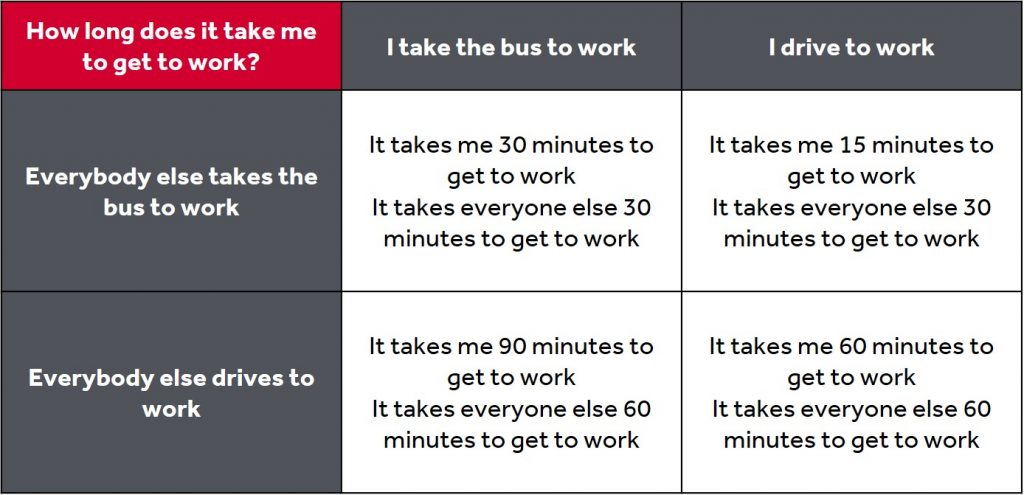

A perfect analogy for acting on climate change is the ‘how long does it take to get to work?’ scenario above, used by Professor Robinson in her lecture. If you choose to drive, and so does everyone else, it takes everyone an hour. If everyone except you chooses to drive to work and you take the bus, it takes you even longer. But if we all took the bus, we could all get to work in 30 minutes.

Government action works

In her lecture, Professor Robinson gave the example of a recent trip she made to Beijing – a city notorious for its air pollution from coal and petrol burning. However when she arrived, she was pleasantly surprised to discover clear air and blue skies.

It transpired that there was a major celebration occurring there that weekend, so the government had snapped its fingers and shut down coal burning and driving of vehicles in the city for the entire preceding month, in order to clear the air for the celebrations. This gives a clear demonstration that if we want to act, we can.

Governments can make choices that serve the public good. Choosing to harm our health through burning fossil fuels is a choice. Why aren’t we making better choices?

The question that we all need to be asking, Professor Robinson says, is: what future will we bequeath to the next generation?

Elizabeth Robinson is Professor of Environmental Economics at the University of Reading, specialising in the management of natural resources in low and middle income countries. She coordinates the working group on exposure and vulnerability of people to climate change for the Lancet Countdown, which tracks the connections between public health and climate change. She is also a member of the Lancet Countdown board. Watch Professor Robinson’s full lecture: