From finding brain changes decades before dementia strikes to exploring the protective effects of speaking another language, Reading researchers are targeting the disease on several fronts. For World Alzheimer’s Day, we spoke to Dr Mark Dallas about some of the University’s cutting-edge research in this area.

Many of us will know someone affected with a dementia like Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia affects 50 million people around the world and that figure is set to reach 152 million by 2050. But we still don’t fully understand the disease nor do we have any treatments. More research is critical.

Charity Alzheimer’s Research UK recently provided renewed funding of £68,500 to the Thames Valley Alzheimer’s Research Network, the partners of which are the Universities of Reading, Oxford and Oxford Brookes. Formerly known as the Oxford network it has been re-named to reflect Reading’s growing contribution.

Early changes

Dementia is slow and stealthy. Changes in brain chemistry that will ultimately lead to the disease can occur in early mid-life, as early as your forties – decades before dementia symptoms appear. These changes involve not just brain cells but also the veins and arteries supplying them and cells responsible for inflammation.

Neuroscientist and network lead Dr Mark Dallas’s research looks at the resident immune cells of the brain, the microglia. In particular, he is investigating their ability to detect these early changes to brain activity before the symptoms of dementia start to be noticeable.

“We believe, alongside other dementia researchers, that these cells that offer insight into brain health. By studying them we hope we can uncover the subtle changes in their own activity that precede the death of nerve cells.

This could bring benefits to people living with dementia in two ways: it could offer the potential for new drug targets and also the ability to get an early diagnosis which will help with long term management of dementia,” he explains.

Bilingual benefits

Brain imaging studies by Dr Christos Pliatsikas from Reading’s School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences are looking at how speaking more than one language can help protect the brain against dementia.

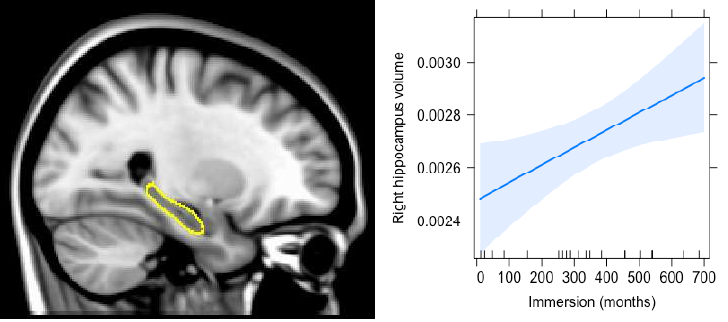

Toms Voits from Christos’s lab recently led a study comparing MRI scans of the brains of healthy bilingual people aged 55 – 65 who have spoken two languages in their everyday life for many years, with those of monolingual people of a similar age.

Findings revealed differences in physical brain structures between the two groups. On average, bilingual people had a greater volume of brain tissue in part of the brain called the hippocampus – responsible for memory and language acquisition – than monolingual people of the same age. In fact, the more time the bilinguals had spent in a country where they actively spoke their second language, the bigger their hippocampus was (see picture below).

Loss of brain processing power as we age is known to happen more slowly in bilingual people. Christos’s work suggests this could be because bilinguals have more tissue to lose and therefore greater protection against the ravages of dementia (the amount of brain tissue lost over the course of Alzheimer’s disease weighs roughly the same as an orange.)

Ongoing work will study 40 bilingual patients diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment to test if differences in brain structure relates to their diagnosis and to their type and amount of bilingual experiences.

Navigating the medicines minefield

Making and attending GP appointments, organising repeat prescriptions and remembering to take both regular and short term medications – navigating the healthcare system to complete these tasks can be a minefield for a person with dementia.

Many hand over control of their medications to a carer – but pharmacist Dr Rosemary Lim’s research is looking at helping people living with the disease to manage their medicines in their own homes and empowering them to be more independent.

“We’ve found that people with dementia come up with strategies of their own, for example ticking medications off on a list or even using Alexa to remind them when to take their medication,” explains Rosemary.

She is working to classify these strategies according to their characteristics and ultimately produce guidelines to help people with dementia to find their way around the system.

In today’s squeezed NHS, community pharmacists have very little time with people with dementia and they can come away with a limited understanding of what drugs they are taking. Another strand of Rosemary’s work is to improve communication between pharmacists and people with dementia, and their carers, to make the most of these short encounters.

Promoting partnerships

With funding secured for another year, the network is in a good position to advance understanding of Alzheimer’s and foster new collaborations.

Mark says: “The award aims to foster new ideas and collaborations to bring about changes to the way we support people living with dementia but also targeting the causes with a view to developing new medicines.”

“For example, the network is closely aligned to the Oxford Drug Discovery Institute, which leaves researchers in Reading and Oxford well placed to take forward findings made at the lab bench into clinical trials.”

Find out more about the ARUK Thames Valley Network Centre

Learn more about Dr Mark Dallas’s research in this video of his 2018 public lecture, ‘Brain Glue: sticking it to dementia’:

Discover more about Dr Christos Pliatsikas’ lab’s research:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=189&v=PgGa5wfb5BU

Dr Rosemary Lim is Associate Professor in the University of Reading’s School of Pharmacy. Her research interests are enhancing and creating safe use of medications in healthcare settings and peoples’ homes. Informed by her experience and training in pharmacy and human factors, she leads and collaborates in research on medication management in dementia, insulin infusions and antimicrobial resistance. Her work is largely collaborative, interdisciplinary and co-produced with users, an approach that she believes is key to generating meaningful and sustainable impact in applied research.