This year, the National Fruit Collection celebrates its 100th anniversary and its 70th year at Brogdale Farm in Kent. Scientific Curator Matt Ordidge reflects on a recent study confirming the parentage of one of the world’s most famous apples, Cox’s Orange Pippin, and the importance of gene banks such as the National Fruit Collection.

Among many historical relationships revealed through recent studies of the genetics of heritage apple cultivars (cultivated varieties), perhaps the most striking is the confirmation of the parentage of Cox’s Orange Pippin. The finding not only acts to correct a misunderstanding that has been documented for over a century, but also helps in untangling the complex relationships in heritage fruit cultivars. A better understanding of these relationships will potentially help breeders in identifying and targeting parental combinations that might produce high quality offspring in the future.

Cox, as it is often known, dates back to around 1825, when it was believed to have been raised as a seedling by Richard Cox at Colnbrook Lawn in Slough. It was first introduced by Charles Turner in around 1850 and received a First Class Certificate from the Royal Horticultural Society in 1962. It has been extensively grown in commercial production both in the UK and overseas, especially in New Zealand. And while the proportion of Cox in UK production has reduced with the planting of more modern cultivars (reducing from 50–70% of home production in the 1980s and 90s to 10–15% in recent years, according to Defra’s Horticultural Statistics 2020), it is still recognised as one of the most famous apples in the world.

Ribston Pippin (a triploid apple dating back to 1707) had been commonly documented as the reputed parent of Cox, despite the general acceptance that triploid apples are often poor at setting seed (a triploid such as Ribston Pippin being an apple with three, rather than the more common two sets of chromosomes). This had been continually repeated from before the time of The Fruit Manual (Hogg, 1884) through the National Apple Register of the UK (Smith, 1971) to the current listings in the National Fruit Collections database maintained by the University. It was considered common knowledge among the heritage apple and horticultural community.

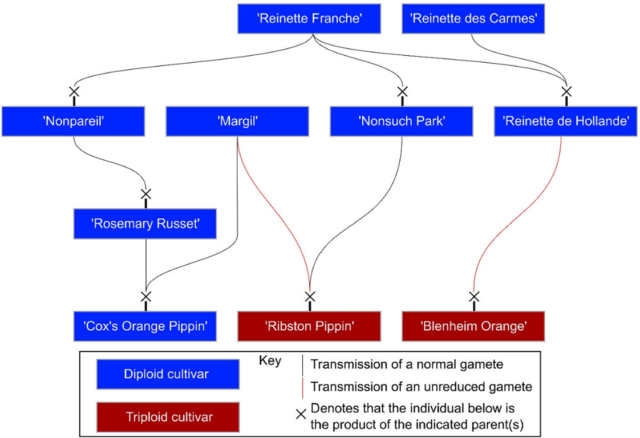

The finding in a recent paper, led by Nick Howard of the universities of Oldenburg and Minnesota, in collaboration with myself and colleagues in France, Germany, Italy, and the USA, focused initially on the relationships between triploid apples and their parents. The study completed a series of findings, beginning with the initial finding that the old cultivar Margil was one of the likely parents of the triploid Ribston Pippin.

This initial finding of Margil as a parent of Ribston Pippin was further developed by the work published by Muranty et al., again in collaboration with myself and other colleagues across Europe. While elucidating a whole series of further pedigrees, the paper confirmed that genetic data pointed to Margil also being one of the parents of Cox. This would appear to be plausible since Margil was itself known in England before 1750 and prior to that in Europe. The genetic evidence appeared to exclude Ribston Pippin as a possibility.

The initial finding by Ordidge et al. was based on identifying the similarity between a diploid-gamete donating parent and the triploid offspring. In the simplest form, a triploid will have inherited a complete set of chromosomes from one parent (the diploid-gamete donor) in addition to a – more conventional – half set of chromosomes from the other parent. And the consequence of this is that a triploid offspring will be significantly more genetically similar to its diploid-gamete donor than to its other parent.

The new study aimed to build on this approach using a significantly larger dataset and a more elegant method of following specific genetic markers through their linkage in groups within individual chromosomes. In addition to confirming a number of other findings from Ordidge et al., this led to the identification of numerous further donors of diploid gametes to triploid offspring. But, the study also brought together a wider range of more common haploid gamete donating parents (producing diploid offspring) and one of these, Rosemary Russet was confirmed as the missing second parent to complete the Cox pedigree.

Through the use of vegetative propagation (grafting) and with the help of gene banks such as the National Fruit Collection, historic cultivars remain available, and able to continue to produce offspring to this day. There is no avoiding the potential of paternity testing (even after nearly 200 years) in the world of heritage fruit!

Dr Matt Ordidge is a Senior Research Fellow in the School of Agriculture, Policy and Development at the University of Reading.

Read more about the National Fruit Collection.