Professor Elizabeth Robinson, whose research contributes to The Lancet Countdown, explores how actions that individuals and governments can take to improve our health can also help to curb climate change.

We have known about climate change for many decades. We know that the planet is warming, extreme weather conditions are becoming more frequent, and that sea levels are rising. But we have not necessarily thought so much about the links between climate change and health.

Countries might do well to focus on those actions that both improve the health of their populations and curb climate change.

For example, efforts to reduce air pollution, encourage healthy eating and a more plant-based diet, increase ‘active transport’ such as walking and cycling, and enhance urban green spaces benefit our health and wellbeing and reduce pressures on a country’s public health services. In making these changes, a country contributes to the global public good of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

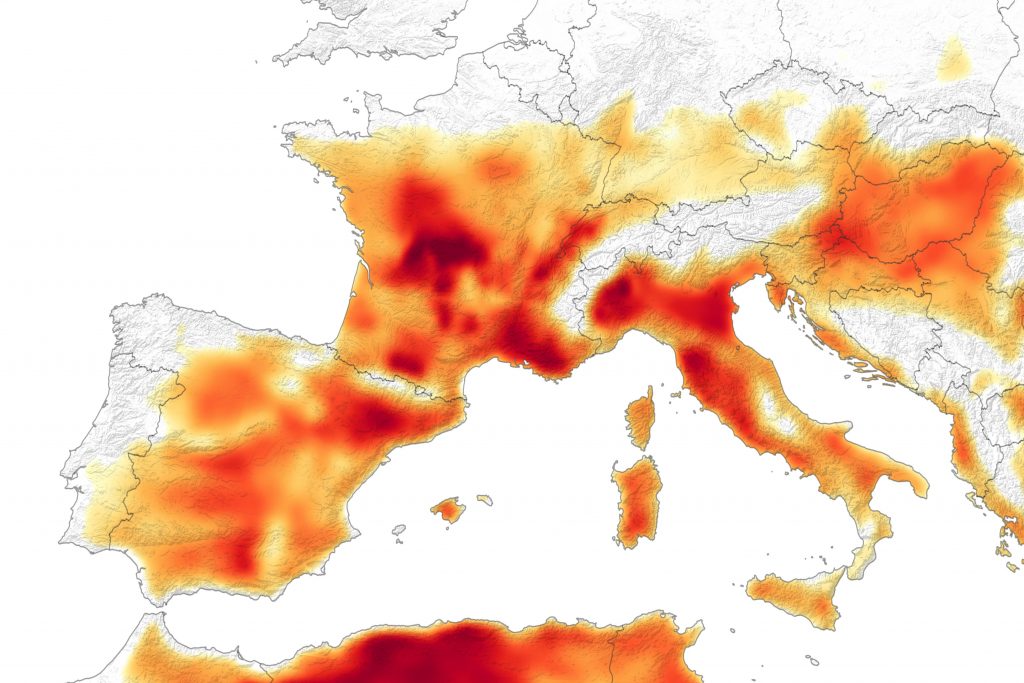

Heatwave deaths

Research done by the authors of the Lancet Countdown annual report suggests that climate change is already putting our health and our healthcare systems under considerable pressure.

Around 70,000 excess deaths were caused by heatwaves in Europe in 2003, with around 15,000 of those excess deaths in France alone. Even though higher temperatures were experienced this year, far fewer excess deaths were recorded in France this year: 1,500.

France achieved this in part through a raft of measures, including an early warning system, the establishment of cooling centres, and regulations concerning access to an air-conditioned room in nursing homes.

Yet even in a higher income country such as France, those who are particularly vulnerable may not be able to avoid exposure to these increasingly frequent high temperatures. It is relatively easy to adapt in a higher income country, but much harder in a lower-income country.

Of course, as countries grow economically, they will be able to afford to take measures to deal with heatwaves. But at some point, it becomes very difficult to protect people from heat.

Above 35 degrees C we need to be able to sweat to keep our core at a safe level. When the air is sufficiently full of water vapour, sweat no longer evaporates and we cannot cool down. If we cannot avoid the heat, we die. Already there may be places where it is simply too hot to be outside, and there are cases of otherwise healthy people are dying from excessive heat.

We can tell a similar story for crops. Although some crops may benefit from both increased carbon dioxide in the air and warmer growing seasons, already we can see the detrimental impacts of excessive heat on crop yield potential, and harvest losses due to the increased frequency of extreme weather events such as droughts and floods. Despite increases in total food production, the number of under-nourished people globally has been increasing since 2014, and climate change is part of the reason.

Public health benefits for all

An individual country has little control over the increasing heat, heatwaves, and extreme weather events due to the global climate crisis. That is why international agreements on climate action are so important. Of course many people would argue that higher-income countries have a moral responsibility to rapidly reduce their emissions, with or without international cooperation. Yet many seem reluctant to act.

But there are several areas where win-win outcomes could be achieved. This could be done without the need for international cooperation, and without countries putting off actions because they would incur the relatively high costs whilst the rest of the world shared in the benefits without bearing any of the costs. Public health is one such area.

Individuals and governments often make choices that harm their health, put pressure on their public health services, and harm the planet through increased emissions. This suggests scope for action which is relatively uncontroversial for an individual or for an individual country government, by instead making choices that improve health and reduce emissions.

But even these choices can be difficult to implement. This could be partly down to inertia: we are used to things happening in a certain way. This could be because making change can be difficult or costly in the short run, so we put off making changes. This might also be because individual actions require support from the government.

Actions that individuals and governments can take

Many of us could be healthier if we walked, cycled, and used public transport more, rather than using our cars. In the process, air pollution would be reduced. But for many of us, society has evolved in a way in which using our cars is much more convenient, and walking or cycling may not feel so safe. So we need our governments to create an environment of safe walking and cycling spaces. We need them to provide affordable and reliable public transport.

Many people could improve their health if they reduced their meat and dairy consumption and ate a more plant-based diet. In the process greenhouse gas emissions could be reduced.

Making that change, learning to cook with and eat different ingredients, ensuring a balanced diet, can be a steep learning curve. It could also threaten the livelihoods of our farmers.

But if we choose a nutritionally balanced diet that includes more locally produced plant-based options, sustainably produced milk, egg and meat products, and purchase and use responsibly to minimise waste, this could benefit our health, our domestic agriculture sector, and contribute to reduced emissions.

Finally, there is increasing evidence that our mental health and wellbeing can be improved if we have access to more green urban spaces. England is well below its target for tree planting, which is needed to help the country reach its emissions reduction target. Planting trees in cities can help to achieve this target and improve wellbeing.

Elizabeth Robinson is Professor of Environmental Economics at the University of Reading, specialising in the management of natural resources in low and middle income countries. She coordinates the working group on exposure and vulnerability of people to climate change for the Lancet Countdown, which tracks the links between public health and climate change. On 15 October she gave a public lecture at the University of Reading, Climate change: Turning up the heat on our health.