Medicines are not normally needed to treat monkeypox. The illness is usually mild and most people infected will recover within a few weeks without needing treatment. But there are vaccines that can be used to control monkeypox outbreaks, which some countries are already using. And treatments do exist for those who become quite ill from the virus.

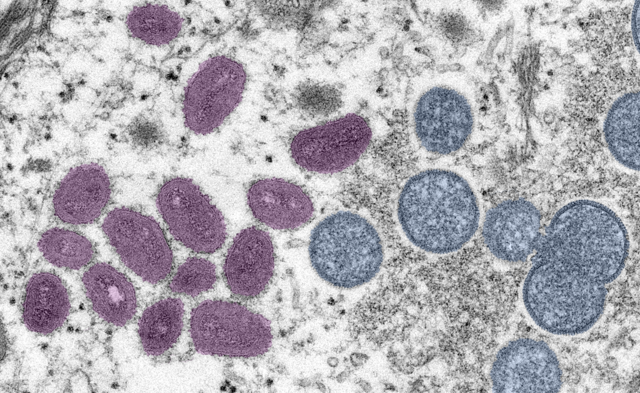

Monkeypox belongs to the Orthopoxvirus genus of viruses, which includes smallpox. Luckily, due to something called cross-protection, smallpox vaccines also work for monkeypox.

Although the world was declared free of smallpox in 1980, many countries keep stocks of smallpox vaccines for emergencies. For example, the smallpox vaccine is used to protect laboratory workers who accidentally come into contact with pox viruses (such as monkeypox or vaccinia – a pox virus that is similar to smallpox but less harmful). They are also kept in case of a terrorist attacks that might use smallpox as a biological weapon.

Smallpox vaccine can be up to 85% effective in stopping infection with the monkeypox virus if it is given before people are exposed to the virus.

There are two types of smallpox vaccine. Both types are based on the vaccinia virus. An older type of smallpox vaccine contains the “live” vaccinia virus. The main one in this group is ACAM2000, which is approved in the US for protecting people against smallpox.

Although ACAM2000 cannot cause smallpox, the vaccinia virus it contains can replicate after the vaccine is given, transmitting from the vaccinated person to an unvaccinated person who comes into close contact with the injection site or any leaking fluid for up to 21 days afterwards.

This also means that ACAM2000 can cause many side effects and shouldn’t be given to at-risk groups, such as pregnant or breastfeeding women, and those with weakened immune systems. People with weakened immune systems, including those with HIV, can get very ill from the vaccine.

The other “live” vaccinia virus is the Aventis Pasteur Smallpox Vaccine. It is not formally approved, but can be made available if other supplies run out.

A newer type of smallpox vaccine, called Imvanex, contains a live but modified form of the vaccinia virus called vaccinia Ankara. Imvanex, made by Danish biotechnology firm Bavarian Nordic, has been licensed in the European Union for preventing smallpox.

In the US, the vaccine goes by the brand name Jynneos and is licensed for preventing both smallpox and monkeypox in adults at risk of these diseases. Jynneos has been used in the UK in previous monkeypox cases.

Because Bavarian Nordic vaccines are made of a modified form of the vaccinia virus, they are considered safe for people in at-risk groups.

It would usually take between five and 21 days for someone who comes into close contact with an infected person to show symptoms of monkeypox (and most likely seven to 14 days) so it is hard to tell if giving the vaccine after someone has been exposed to monkeypox will fully protect them. However, the recommendation in the US and the UK is that, after a risk assessment, people exposed to the monkeypox virus are offered a modified vaccinia Ankara vaccine dose as soon as possible, ideally within four days, but up to 14 days afterwards.

Antivirals

Apart from vaccines, there are some medicines that could be used for treating monkeypox.

One such drug is tecovirimat which stops the spread of infection by interfering with a protein found on the surface of Orthopoxviruses.

Tecovirimat is approved in the US for treating smallpox only. It has been tested in healthy humans and shown to stop the smallpox virus in the lab. However, it has not been tested in people with smallpox or other Orthopoxviruses. Still, in Europe tecovitimat has been authorised for treating smallpox, monkeypox and cowpox under exceptional circumstances.

Another antiviral that might be used is cidofovir – an injectable drug licensed in the UK to treat a serious viral eye infection in people with Aids.

In the body, cidofovir is converted into the antiviral ingredient cidofovir diphosphate. Because cidofovir stops smallpox in the laboratory, it could be authorised for emergency use in smallpox or monkeypox outbreaks.

However, cidofovir is quite a potent medicine and can damage the kidneys, so a better alternative might be the closely related drug brincidofovir, which has been approved in the US for treating smallpox.

Brincidofovir (brand name Tembexa) is given by mouth and can be prescribed to people of any age. Its special design helps get the right amount of the drug into cells to release the cidofovir component and also makes it less damaging to the kidneys.

Brincidofovir has been tested in humans for other viral conditions. Its approval for use in smallpox in the US comes from laboratory studies showing that it works against Orthopoxviruses. For this reason, brincidofovir is also listed as a potential drug for treating monkeypox.

What we still lack, though, is data on how effective cidofovir, brincidofovir and tecovitimat will be in treating monkeypox infections in humans. A recent paper, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases investigated the effectiveness of brincidofovir (three patients) and tecovirimat (one patient) in monkeypox cases between 2018 to 2021 in the UK. The researchers reported poor efficacy for brincidofovir and called for more studies of tecovirimat in human monkeypox infection.

Professor of Social and Cognitive Pharmacy at the University of Reading.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.