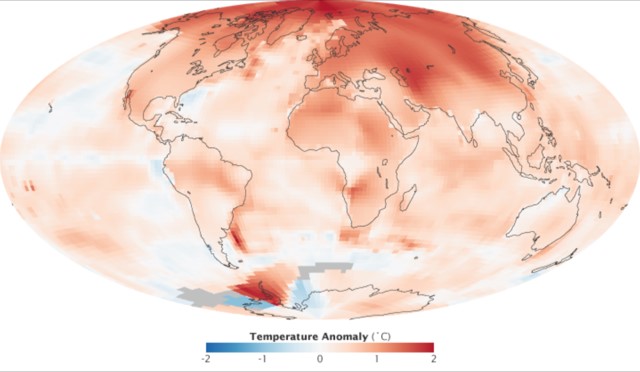

The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the planet and people living in its coastal regions face a real threat of their homes and way of life being swept away by floods. Reading climate scientist Dr Lucia Hosekova recently went there to talk to them about her work.

Few people are more aware of how fast our oceans and climate are warming than polar scientists. The Arctic is now considered the canary in the coal mine that is climate change – the place where warnings are quickly turning into a worrying reality.

Due to an effect known as polar amplification, scientists have observed that temperatures in the Arctic regions are rising roughly twice as fast as the global average temperature. This is a result of a complex system of feedback loops, including the effects of declining sea ice and changes to the temperature profile at varying altitudes.

Arctic outreach

In May 2019, I had an opportunity to visit the cities in the north coast of Alaska as part of a small team of scientists hosting outreach events at schools and community centres. We hoped to engage in a dialogue with indigenous Inupiat communities that would benefit both us and them.

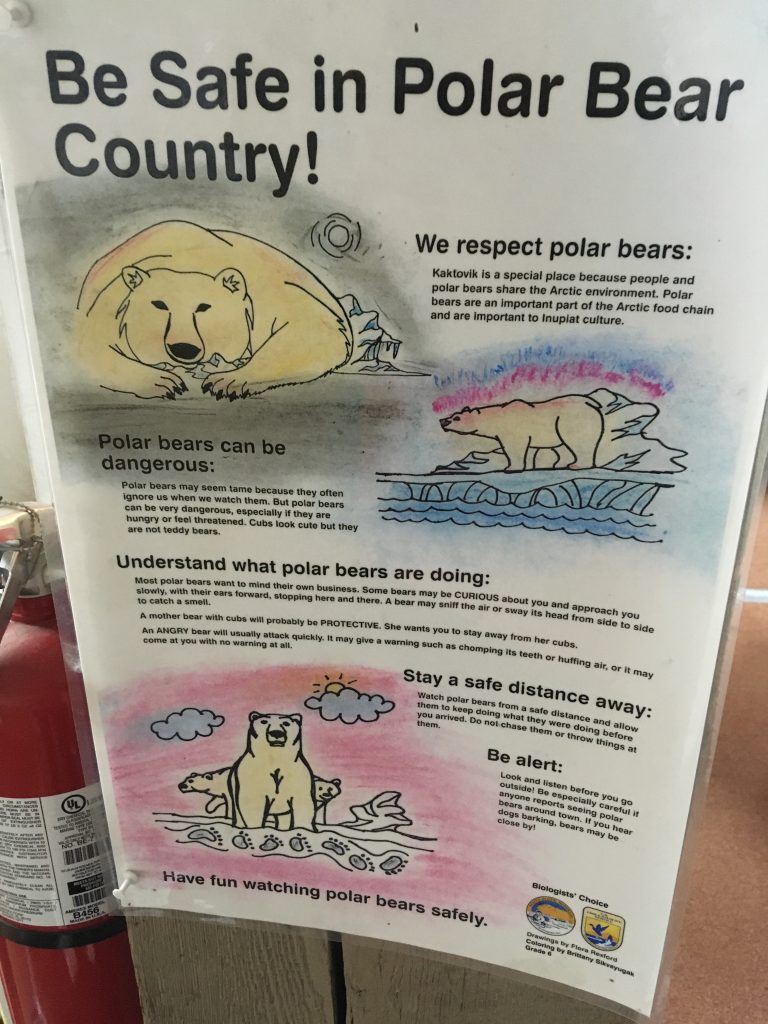

Our first stop was Kaktovik, a town of 300 sitting on an island surrounded by a lagoon on one side, and a beach exposed to Beaufort Sea on the other. This beach, together with many others along the Arctic coastline, is now undergoing erosion at unprecedented rates and leaving many communities exposed to flooding.

From the moment we stepped off the small twin prop plane (the only type capable of landing on a lonely runway that emerged from the surrounding whiteness), I immediately gained respect for the people who, by choice or birth, made their life here in the tundra.

Skidoos and bear guns

There are only two flights a day carrying supplies and people along the coast when the weather permits, so the cities rely on indigenous ways of hunting and beachcombing to provide supplies and food.

There are only two flights a day carrying supplies and people along the coast when the weather permits, so the cities rely on indigenous ways of hunting and beachcombing to provide supplies and food.

Here, the snowmobile helps you reach places once the road inevitably ends. You grab your bear gun before going out as we would take an umbrella back home, and every first-grader learns what temperature and wind speed is safe for playing outside.

We spent two days visiting the local school and talking to students of all ages about the climate and ocean, engaging them in interactive demonstrations.

The children continued to impress: we were rewarded by endless curiosity and questions that showed us that they know all too well how vulnerable their island is to permafrost thaw and waves hitting the beach previously protected by sea ice.

At the end of our visit, we held a community meeting that served as a showcase of our science and the ways it touches the local life.

As we quickly found out, no Inupiat social gathering is complete without a raffle (with prizes ranging from water purifiers to drones) and a generous dinner. It was up to us to be cooks, hosts and scientists at the same time! It was a lot of fun seeing the children we met during our school visits in the company of their older family members. Here’s a little secret: if you want to make an Inupiat friend, bring Tang.

Remote science community

After Kaktovik, we headed to Utqiagvik (previously known as Barrow), the largest settlement in the North Slope Borough and the closest the coast has to a town – here you can find hotels, restaurants, even a Subway.

With access to a large runway and other infrastructure, Utqiagvik is home to a sizeable transient scientific community, occupying a section of the city referred to as NARL (United States Naval Arctic Research Laboratory). In the communal accommodation, we found a vibrant international atmosphere of scientists representing a wide range of fields – from environmental and biological sciences all the way to a NASA team who came to test their new robots in extreme conditions.

The communal meeting we organised here, called ‘Sandwich ’n Science’, reflected this varied demographic. Scientists were joined by locals and interested parties, who were aware and outspoken about the challenges their communities are facing in the near future.

They wanted to know how long it will be before the road they take every day will be flooded on a regular basis, whether they need to move out of their house, and, most importantly, who is going to pay for it. These are all very good questions, and scientists can play a key role in answering them.

Waves of destruction

The US-funded project CODA (Coastal Ocean Dynamics in the Arctic) that sponsored my outreach trip and further collaboration, aims to study the link between coastal erosion and increasing wave activity in the Arctic caused largely by sea ice retreat and diminishing of the natural protection it used to provide to the coast lines.

Waves in the Arctic are a ‘hot’ topic in polar sciences right now as their presence alters the sea ice state, increases energy in the upper ocean and may cause complex thermodynamic feedbacks.

Along with other University of Reading researchers at the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling, I am involved in work to understand the dominant processes in wave-ice interactions and study their impacts on present and future climate in state-of-the-art sea ice models

It is one thing to listen to academic seminars and discussions. But it is quite another to come face-to-face with people for whom the sea ice I mostly know from satellite images is the view from their bedroom window: for them, the effects of polar amplification are a real threat to their way of life.

Not everyone gets to witness the wider consequences of their actions, be it as a scientist or simply as an inhabitant of this planet.

Dr Lucia Hosekova is a post-doctoral research assistant for the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling (CPOM), which is part based at the University of Reading’s Department of Meteorology, and has recently started a role as Visiting Scientist at the Applied Physics Laboratory at the University of Washington as part of the CODA project. Her research interests are polar oceans and sea ice, with a focus on sea ice thermodynamics and the role of wave-ice interactions in the changing climate.

Among a range of polar research projects, CPOM – a NERC centre of excellence – researches physical processes in the Marginal Ice Zone, the area where sea ice is fragmented and exposed to ocean surface waves. Scientists there study how these processes are represented in sea ice and ocean models in order to improve climate simulations.

A version of this post first appeared on the weather and climate departmental blog.